- Home

- Robert Jordan

New Spring: The Novel Page 11

New Spring: The Novel Read online

Page 11

Sheriam was one of those who lingered, and it was in front of her, Siuan and Moiraine that Merean stopped. Moiraine’s heart fluttered, and she struggled to breathe evenly as she curtsied. She struggled just to breathe in the first place. Maybe Siuan had been right. Well, she was right, in point of fact. When Merean said an Accepted might test soon, it always came within the month. But she was not ready! Siuan’s face shone with eagerness, of course, her eyes bright. Sheriam’s lips were parted in hopeful anticipation. Light, every last Accepted must think herself more ready than Moiraine Damodred did.

“You’ll be late if you don’t hurry, child,” the Blue sister told Sheriam sharply. And surprisingly. Merean was never sharp, even when there was punishment in the offing. When she lectured on your misdeeds while applying switch or strap or the hated slipper, her voice was merely firm.

As the fire-haired woman darted away, the Mistress of Novices focused her attention on Siuan and Moiraine. Moiraine thought her heart would pound its way through her ribs. Not yet. Light, please, not yet.

“I’ve spoken with the Amyrlin, Moiraine, and she agrees with me that you must be in shock. The other Accepted will have to make do without you today.” Merean’s mouth tightened for an instant before serenity returned to her face. Her voice remained a needle, though. “I’d have kept you all in, but people will cooperate better with initiates of the Tower than with clerks, even White Tower clerks, and the sisters would be up in arms if they were asked to do the task. The Mother was right about that much.”

Light! She must have argued with Tamra to be upset enough to say all of that to Accepted. No wonder she was being sharp. Relief welled up in Moiraine that she was not to be whisked off and tested for the shawl immediately, yet it could not compete with disappointment. They could reach the camps around Dragonmount today. Well, one of the camps, at least. They could!

“Please, Merean, I—”

The sister raised one finger. That was her warning not to argue, and however kind and gentle she was in the general course of things, she never gave a second. Moiraine closed her mouth promptly.

“You shouldn’t be left to brood,” Merean went on. Smooth face or no, the way she shifted her shawl to her shoulders spoke of irritation. “Some of the girls’ writing is like chicken scratches.” Yes, she was definitely upset. When she had any criticism, however slight, it was delivered to the target of it and no one else. “The Mother agreed that you can copy out the lists that are near unreadable. You have a clear hand. A bit over-flowery, but clear.”

Moiraine tried desperately to think of something to say that the sister would not take for argument, but nothing came. How was she to escape?

“That’s a very good idea, Moiraine,” Siuan said, and Moiraine gaped at her friend in amazement. Her friend! But Siuan went merrily ahead with betrayal. “She didn’t sleep a wink last night, Merean. No more than an hour at most, anyway. I don’t think she’s safe to go riding. She’ll fall off inside a mile.” Siuan said that!

“I’m glad you concur with my decision, Siuan,” Merean said dryly. Moiraine would have blushed to have that tone directed at her, yet Siuan was made of sterner material, meeting the sister’s raised eyebrow with an open-eyed smile of innocence. “She shouldn’t be left alone, either, so you can help her. You have a good clear hand yourself.” The smile froze on Siuan’s face, but the sister affected not to notice. “Come along, then. Come along. I’ve more to do today than usher the pair of you around.”

Gliding ahead of them like a plump swan on a stream, a fast-swimming swan, she led the way to a small windowless room a little down from the Amyrlin’s apartments and across the corridor. A richly carved writing table, with two straight-backed armchairs behind it, held a tray of pens, large glass ink jars, sand jars for blotting, stacks of good white paper, and a great disorderly stack of pages covered in writing. Hanging her cloak on a peg and setting her scrip on the floor by the table, Moiraine stared at that ragged pile as glumly as Siuan did. At least there was a fireplace, and a fire going on the narrow hearth. The room was warm compared to the corridors. Much warmer than a ride in the snow. There was that.

“Once you’ve finished breakfast,” Merean said, “come back here and set to work. Leave the copies in the anteroom of the Amyrlin’s study.”

“Light, Siuan,” Moiraine said with feeling as soon as the sister was gone, “what made you think this was a good idea?”

“You—” Siuan grimaced ruefully. “We will get a look at more names this way. Maybe all the names, if Tamra keeps us in the job. We could be the first to know who he is. I doubt there could be two boys born on Dragonmount. I just thought it would be ‘you,’ not ‘us.’” She breathed a gloomy sigh, then suddenly frowned at Moiraine. “Why would you be brooding? Why are you supposed to be in shock?”

Last night, revealing her woes had seemed out of place, a trifle compared to what they knew the world faced, but Moiraine had no hesitation in telling her now. Before she finished, Siuan enveloped her in a strong, comforting hug. They had wept on each other’s shoulders much more often than either had availed herself of Merean’s. She had never been as close to anyone as she was to Siuan. Or loved anyone as much.

“You know I have six uncles who are fine men,” Siuan said softly, “and one who died proving how fine a man he was. What you don’t know is, I have two others my father wouldn’t let cross his doorstep, one his own brother. My father wouldn’t even say their names. They’re street robbers, shoulderthumpers and drunkards, and when they’ve guzzled enough ale, or brandy if they’ve stolen enough to afford it, they start fights with anyone who looks at them the wrong way. Usually, it’s both of them together setting on the same poor fellow with fists and boots and anything that comes to hand. One day, they’ll hang for killing somebody, if they haven’t already. When they do, I won’t shed a tear. Some people just aren’t worth a tear.”

Moiraine hugged her back. “You always know the right thing to say. But I will still pray for my uncles.”

“I’ll pray for those two scoundrels when they die, too. I just won’t fret myself over them, alive or dead. Come. Let’s go to breakfast. It’s going to be a long day, and we won’t even have a nice ride for exercise.” She had to be joking, yet there was not so much as a twinkle of mirth in her blue eyes. Then again, she truly did hate doing clerical work. No one enjoyed that.

The dining hall most often used by Accepted lay on the lowest level of the Tower, a large room with stark white walls and a white-tiled floor, full of long, polished tables, and plain benches that could hold two women, or three at a pinch. The other Accepted ate quickly, sometimes gulping their food with unseemly haste. Sheriam spilled porridge on her dress and hurried from the room proclaiming that she had time to change. She very nearly ran. Everyone was hurrying. Even Katerine all but trotted off, still eating a crusty roll and brushing crumbs from her dress. It seemed a chance to leave the city was not so miserable, at that. Siuan dawdled over her porridge, laced with stewed apples, and Moiraine kept her company with another cup of strong black tea containing just a drop of honey. After all, the chance that the boychild’s name was among those awaiting them had to be vanishingly small.

Soon they were alone at the tables, and one of the cooks came out to frown at them, fists planted on her hips. A plump woman in a long, spotless white apron, Laras was short of her middle years and more than pretty, yet she could frown a hole through a stone. No Accepted was ever fool enough to come over high-handed with Laras, at least not more than once. Even Siuan gave way beneath that unwavering gaze, hastily spooning the last bits of apple from her bowl. Laras began calling for the scullions to bring their mops before Siuan and Moiraine reached the door.

Moiraine expected the work to be drudgery, and it was, though not so bad as she had feared. Not quite so bad. They began by digging their own lists out of the mound, and added those already in a readable hand, which reduced the stack by half. But only by half. If you came to the Tower unable to write, you were tau

ght a decent hand as a novice, but those who came writing badly often took years to reach legibility, if they ever did. Some full sisters used the clerks for anything they wanted someone else to understand.

Most of the lists appeared to be shorter than hers and Siuan’s, yet even counting Meilyn’s explanation, it seemed that an astonishing number of women had given birth. And this was only from the camps nearest the river! Noticing Siuan scanning each page before setting it to one side, she began doing the same. Without any great hope, yet vanishingly small was not the same as impossible. Except that the more she read, the further her spirits fell.

Many of the entries were shockingly vague. Born within sight of Tar Valon’s walls? The city’s walls were visible for leagues, visible from the slopes of Dragonmount. This particular child was a girl, with a Tairen father and a Cairhienin mother, yet the note boded ill for locating the boychild. There were far too many like that. Or, born in sight of the White Tower. Light, the Tower could be seen from nearly as far as Dragonmount! Well, from a good many miles, at least. Other entries were sad. Salia Pomfrey had given birth to a boy and had left to return to her village in Andor after her husband died on the second day of fighting. There was a note beneath the name, in Myrelle’s flowing script. Women in the camp tried to dissuade her, but she was said to be half mad or more from grief. Light help her. Sad to weeping. And in a colder vein, as troubling as the inexact entries. No name was recorded for her village, and Andor was the largest nation between the Spine of the World and the Aryth Ocean. How could she be found? Salia’s child had been born on the wrong side of the Erinin and too early by six days, but if the Dragon Reborn’s mother was like her, how could he be found? The pages were dotted with names like that, though usually they seemed to be women others had heard of, so the information might be written in full elsewhere. Or it might not. The task had seemed so simple when Tamra set it.

The Light help us, Moiraine thought. The Light help the world.

They wrote steadily, sometimes putting their heads together to decipher a hand that really did resemble chicken scratches, took an hour at midday to go down to the dining hall for bread and lentil soup, then returned to their pens. Elaida appeared, in a high-necked dress even redder than that she had worn the day before, to stride around the table and silently stare over first Siuan’s shoulder and then Moiraine’s as though to study their writing. Her red-fringed shawl was richly embroidered with flowered vines. Flowered and, more fittingly, barbed with long thorns. Finding nothing to criticize, she left as abruptly as she had come, and Moiraine echoed Siuan’s sigh of relief. Other than that, they were left alone. When Moiraine dusted her last page with fine sand and poured it into the wooden box sitting on the floor between the chairs, the hour for supper had come. A number of boychildren had been born yesterday—the birth had to come after Gitara’s Foretelling—but not one had seemed remotely possible for the child they sought.

After a night of troubled, restless sleep, she needed no urging from Siuan to return to that small room rather than joining the other Accepted hurrying to the stables. Though some were not hurrying so quickly, today. It seemed that even a trip outside the city could pall when all you had to do was sit on a bench and write names all day. Moiraine was looking forward to writing names. No one had told them not to, after all. And they had been wakened by the sounds of the other women getting ready, not by a novice bringing orders to ride out with the rest. As Siuan often said, it was easier to ask forgiveness than permission. Though the Tower was rather short on forgiveness for Accepted.

Yesterday’s gleanings were waiting on the table, an untidy stack as tall as the first had been. While they were sorting out the readable lists, two clerks walked in and stopped in surprise, a stout woman with the Flame of Tar Valon worked on one dark sleeve, her gray hair in a neat roll on the nape of her neck, and a strapping young fellow who looked more suited to armor than to his plain gray woolen coat. He had beautiful brown eyes. And a lovely smile.

“I dislike being set a task only to learn someone else is already performing it,” the woman said acerbically. Noticing the younger clerk’s smile, she shot him a cold stare. Her voice turned to ice. “You know better than that if you want to keep your place, Martan. Come with me.” Smile sliding away in worry and red-faced with embarrassment, Martan followed her from the room.

Moiraine looked apprehensively at Siuan, but Siuan never stopped sorting. “Keep working,” she said. “If we look to be busy enough….” Her voice trailed off. It was a small hope, if clerks had been assigned the work, but it was all they had.

By a matter of minutes they managed to be copying names by the time Tamra herself walked into the room. Wearing plain blue silk today, the Amyrlin was Aes Sedai calm made flesh. No one would have thought that her friend had died right in front of her only the day before yesterday, or that she was waiting on a name that would save the world. Tamra was followed closely by the gray-haired clerk, who wore satisfaction on her face like too much rouge, and young Martan stood behind her, smiling over her shoulder at Moiraine and Siuan. He really would lose his place if he did that too often.

Moiraine bobbed to her feet and offered her courtesies so fast that she forgot the pen in her hand. She felt it twist, though, and winced at the ink stain it left, a black smear spreading to the size of a coin on the white wool. Siuan was just as quick, but much more steady. She remembered to lay her pen on the tray before spreading her skirts. Calm, Moiraine thought. I must be calm. Running through the mental exercises did little good.

The Amyrlin studied them closely, and when Tamra scrutinized someone, the most thick-skinned and insensitive felt measured to the inch and weighed to the ounce. Moiraine only just managed not to shift in unease. Surely that gaze would see everything they planned. If that could be graced with the name of plan.

“I had intended you to have a freeday, to read or study as you chose,” Tamra said slowly, still considering them. “Or perhaps to practice for your testing,” she added with a smile that did nothing to lessen her scrutiny. A long pause, and then she nodded slightly to herself. “You are still troubled by your uncles’ deaths, child?”

“I had nightmares again last night, Mother.” True, but once more they had been of a baby crying in the snow, and a faceless young man breaking the world anew even while he saved it. The steadiness of her own voice amazed her. She had never thought she would dare give an Aes Sedai answer to the Amyrlin Seat.

Tamra nodded again. “Very well, if you think you need to be occupied, you may continue. When the boredom of copying all day overcomes you, leave a note with your finished work, and I will see to replacing you.” Half turning, she paused. “Ink is very difficult to remove, especially from white cloth. I won’t tell you not to channel to do it; you know that already.” Another smile, and she gathered up the gray-haired clerk, herding her from the room. “No need to look so indignant, Mistress Wellin,” she said soothingly. Only fools upset clerks; their mistakes, accidental or on purpose, could cause too much damage. “I’m sure you have much more important tasks than….” Her voice faded to a receding murmur in the corridor.

Moiraine lifted her skirt to look at the stain. It had spread to the size of a large coin. Ordinarily, removing it would require hours of careful soaking in bleach that stung your hands and offered no guarantee of success. “She just told me to use the Power to clean my dress,” she said wonderingly.

Siuan’s eyebrows attempted to climb atop her head. “Don’t talk nonsense. I heard her as well as you, and she said nothing of the sort.”

“You have to listen to what people mean as well as what they say, Siuan.” Interpreting what others really meant was integral to the Game of Houses, and put together, Tamra’s smile, the cast of her eye, and the phrasing she had used were as good as written permission.

Embracing the Power, she wove Air, Water and Earth exactly so, laying the weave atop the stain. Just because Accepted were forbidden to channel to do chores did not mean they were not taught

how; there was no such prohibition for sisters, who frequently traveled without a maid. The black smear suddenly glistened wetly and began to shrink, rising onto the surface of the wool as it did. Smaller and smaller it became, until it was only a small ebon bead of dried ink that fell into her cupped palm.

“I might keep this as a memento,” she said, setting the black bead on the edge of the table. A reminder that Siuan had been correct. There were times when the rules could be broken.

“And if a sister had walked in?” Siuan asked wryly. “Would you have tried to tell her it was all part of the Game of Houses?”

Moiraine’s face grew hot, and she released the Source. “I would have told her…. I would have…. Must we talk of this now? There must be as many names as yesterday, and I would like to finish before supper is done.”

Siuan laughed uproariously. You might have thought the redness of Moiraine’s face was a fool’s paint.

They had been writing above an hour when Moiraine came to an entry that gave her pause. Born in sight of Dragonmount, it said, which was as ridiculous as saying in sight of the Tower. But Willa Mandair had given birth to a son, west of the river, and on the day of Gitara’s Foretelling. She copied the entry slowly. Raising her pen at the end, she did not dip it in the ink jar or look for the next name in Ellid’s spiky hand. Her gaze rose to the ebon bead. She was one of the Accepted, not a sister. But she would be tested soon. Bili Mandair could have been born on the riverbank and his mother still have been in sight of Dragonmount. But nothing Ellid had written indicated how far the camp she had gone to was from the mountain. Or how close. The earlier entries just said “born in Lord Ellisar’s encampment outside Tar Valon.”

Conan the Unconquered

Conan the Unconquered Conan the Triumphant

Conan the Triumphant The Eye of the World

The Eye of the World The Great Hunt

The Great Hunt Conan the Victorious

Conan the Victorious The Dragon Reborn

The Dragon Reborn The Fires of Heaven

The Fires of Heaven Winter's Heart

Winter's Heart Lord of Chaos

Lord of Chaos The Shadow Rising

The Shadow Rising Conan the Defender

Conan the Defender The Strike at Shayol Ghul

The Strike at Shayol Ghul The Path of Daggers

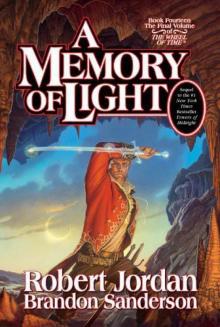

The Path of Daggers A Memory of Light

A Memory of Light Knife of Dreams

Knife of Dreams Crossroads of Twilight

Crossroads of Twilight Conan the Invincible

Conan the Invincible The Gathering Storm

The Gathering Storm Warrior of the Altaii

Warrior of the Altaii A Crown of Swords

A Crown of Swords The Wheel of Time

The Wheel of Time Towers of Midnight

Towers of Midnight Conan Chronicles 2

Conan Chronicles 2 Conan the Magnificent

Conan the Magnificent New Spring

New Spring What the Storm Means

What the Storm Means A Memory of Light twot-14

A Memory of Light twot-14 New Spring: The Novel

New Spring: The Novel Towers of midnight wot-13

Towers of midnight wot-13 A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14

A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14 A Crown of Swords twot-7

A Crown of Swords twot-7 Lord of Chaos twot-6

Lord of Chaos twot-6 The Great Hunt twot-2

The Great Hunt twot-2 The Shadow Rising twot-4

The Shadow Rising twot-4![Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/03/wheel_of_time-11_knife_of_dreams_preview.jpg) Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams

Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams The Dragon Reborn twot-3

The Dragon Reborn twot-3 The Wheel of Time Companion

The Wheel of Time Companion The Fires of Heaven twot-5

The Fires of Heaven twot-5 Prologue to Towers of Midnight

Prologue to Towers of Midnight The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8

The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8 The Path of Daggers twot-8

The Path of Daggers twot-8 By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light

By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light Crossroads of Twilight twot-10

Crossroads of Twilight twot-10 The Gathering Storm twot-12

The Gathering Storm twot-12 Winter's Heart twot-9

Winter's Heart twot-9 Knife of Dreams twot-11

Knife of Dreams twot-11 New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)

New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)