- Home

- Robert Jordan

Warrior of the Altaii Page 12

Warrior of the Altaii Read online

Page 12

When they did come they were the first to pass since the kitchen girl. They were a different pair than the ones who’d brought me there. They didn’t speak at all. They led me straight down to the garden, where Elana was waiting with her women.

Once again, I fed from their fingers, crawling on hands and knees. Once again I drank from their cupped hands. Because I was clean they patted me the way they would a dog, and they were freer with their laughter and their comments. Some were as ribald as those of Lura and Tnay and the other bath girls.

When my brief time in the garden court was done I was returned to the alcove. There I sat in utter solitude until it was time to be fed by Elana in the garden again. From the garden I went to the bath, where the same dull bath girls bathed me. So passed the day. Unrelieved drabness around two bits of color, both centered on Elana. Could her scheme work even when I knew what she tried?

The guard had given me directions for my escape. It would take more than a few days to regain my strength on the tidbits they fed me in the garden, but when I did, I had to be free of the chain to make use of the directions. It wasn’t like the chain in the cell. It had no cap, merely a bolt set in the wall. I knew it wouldn’t move, but I braced my feet on either side of it, took up the slack in the chain and pulled with all my strength.

“You won’t get free like that.”

I twisted around to find the kitchen girl regarding me studiously. “You again,” I said. “Why?”

“I heard something about you. I thought I’d seen healed whip marks on your back, but I couldn’t be sure until now. They say in the slave quarters that you took a hundred lashes without making a sound, or even flinching. They say that Nesir was so frightened of you that he wouldn’t free you himself after.”

“They seem to say a lot of things,” I said dryly, “and only a little of it true.”

“But how could you do it? I cry when Cook hits me with her spoon.” She rubbed at her hip reflectively.

“Perhaps you don’t have enough reason not to cry, or maybe you know Cook has good cause to hit you.”

“Not always.” She looked down the hall and frowned. “Could I sit in there with you? You wouldn’t hurt me, or—I mean—”

“I won’t hurt you, girl,” I said, and she scurried into the alcove, a bag I hadn’t noticed clutched to her breast. “I never see anyone here except for you. And the guards, of course. I didn’t think any pretty women were to be allowed near me.”

She froze half seated. “You won’t tell? Please?”

“If I was a slave, I’d tell.”

She puzzled over that for a minute, then smiled and settled to the floor. “But you’re not really a slave, so you won’t carry tales like one. And thank you.”

“For what? I won’t tell because I don’t want to.”

“No,” she said shyly. “For saying I’m pretty. Cook sometimes says I think I am, but then she always takes a strap to me. And she always gives me work where I’m so dirty I couldn’t tell if I was or not.”

“You’ve never seen a mirror?”

“There are no mirrors in the kitchens.” She set the bag on the floor. “I brought this, because of what you did.” From the bag she took a piece of meat, bread, cheese and fruit. “I tried to get wine, but I couldn’t.”

“Why, child?”

“Because.” It was as if she thought I should know the answer. “I have to go now.” She gathered up her bag and peered around the corner into the hall.

“Girl.” She stopped at the word. “You’ve not told me your name.”

“Nilla,” she said. “I’m called Nilla.” Like a wraith she disappeared.

Elana began to remark on my trips to the garden that the food was agreeing with me, that I was regaining lost flesh. It wasn’t her food that did it, but the food that Nilla brought every night, food stolen at great risk to herself, I had no doubt, from the kitchens.

At first I asked her every time why she did it. Being caught would’ve meant the displeasure of Elana, and for a kitchen girl that could be worse than death. She never gave an answer, or gave the same one as the first time I asked, because. She’d try to change the subject, talk of other things, and I didn’t try and force her. I’ve never professed to know much of the minds of women, but she began to convince me I knew nothing.

We talked at each visit until she had to leave. Sometimes she’d share the food with me, but usually she said she was fed better than I was. She did talk with intelligence, though, and one night I learned how she came to be a kitchen girl.

“I’m the daughter of a farmer near Knorros,” she said. “My parents allowed me to spend my days reading and dreaming, instead of making me work on the land, but I came to realize that I was bound to be a burden to them. I looked as if I was made of sticks, and my father couldn’t provide a very large dowry, so I knew I’d never be able to get a husband to help work my father’s lands or grandchildren to provide for him when he was old.”

“You should have waited,” I said. “They’d not want a dowry if they saw you now.”

“But I didn’t wait. I set out for Knorros. I thought I’d find work and save enough money in a few years to hire a laborer who’d take care of the farm when they were old. I suppose I was innocent, even for a country girl. I didn’t even get to Knorros before a slaver found me. When he saw what he’d gotten he said it wasn’t worth stopping to take me, but since he’d already stopped, he’d carry me along. I’ve seen coffles of slavers since then, and all their women were beautiful, but this one was third-rate, dealing in laborers, and I was pretty enough for him. He sold me here three years ago to work in the palace kitchens.”

With her talk to heal my mind and her food to heal my body I regained most of the weight I’d lost by the third tenday in the alcove. The strength, however, would take longer, I knew. I didn’t get it.

On my thirtieth day there, while I waited for the afternoon journey to the garden, guards came. Not the pair who’d always come before, but a full twenty. A new page was turning in the book, and I didn’t think I’d like what was written on the other side.

XIV

TWISTING SHADOWS

Twenty men can’t be called a guard for one man. They have to be considered an escort. So they escorted me to a part of the palace I’d not seen before, a large, open room that must have been the top of a tower for all its size, for it had huge arched windows on all sides leading out onto a balcony. The ceiling was a dome that stretched out of sight, covered with strange symbols. Some of them I thought I’d seen Mayra use.

They pushed me to the center of the room and bound my hands and feet to a ring set in the floor, so I had no choice but to kneel there. When I saw what I was kneeling on, I wished I’d fought them.

I was in the middle of a large five-pointed star, worked into the stone. Inside the star was a goat’s head, his ears in two points of the star, his horns in two, and his beard in the fifth. Even the pit, I thought, might be preferable.

From somewhere behind me five women entered the room. Eilinn and Elana were coldly formal toward each other. Of the others I recognized only Sayene, but something in the dress of the others made me remember names half heard in the garden, Ya’shen and Betine. Three Sisters of Wisdom, a sacred number magnifying their powers, and I knelt on a symbol of power, a focus of darkness.

“I still don’t think this is necessary,” Elana said angrily.

“Once again, my queen,” said Sayene, “let me explain.” Her voice sounded as if she’d held on to the proper tone with difficulty. “You don’t want to kill him. That means he must be neutralized. If that can be done perhaps the other matter can be disposed of, and all will still be as it must be. If not—”

“I don’t like this hiding of things,” said a beautiful woman. “This one. The other one. These are times of power, and happenings of power. There is no time for childish hiding games.”

“You forget who you’re speaking to, Ya’shen,” Elana snapped. “I am the power here. I am

the Queen of Lanta, and I don’t like you poking into what I do with your spells and magic.”

“You’re not the only power in Lanta,” Eilinn broke in, “or the only queen.”

“If you please,” said the third Sister of Wisdom, the one who must be Betine, “this is not the time for squabbling. Let us do what we came here to do. Then we can all get on with more important matters.”

They all fell silent, though Eilinn and Elana still eyed one another with looks that could wound flesh. The three Sisters of Wisdom ranged themselves around the star. Betine and Ya’shen each stood before a horn. Sayene stood at the beard and faced me where I knelt between the eyes. They let their robes fall to the stone.

Sayene lit a candle and stepped into the star. I heard the pad of feet behind me and knew that the others had done the same. Sayene knelt and put the candle before her. I tugged at the ropes, but there was no give in them. They cut into me from the effort.

“Maji Kwa,” intoned Sayene.

“Maji Kwa,” the others repeated.

“Imholith.”

“Imholith.”

“Catal Kendora Amarane.”

“Catal Kendora Amarane.”

The daylight from outside seemed cut off. The air thickened around me, caught in my throat like jelly. Their voices quickened, the responses falling hard on the heels of Sayene’s lead.

“Mahera Tras!”

“Mahera Tras!”

“Rajinga!”

“Rajinga!”

“Lac Dakoro!”

“Lac Dakoro!”

Dizziness tugged at me, and only a single tube of vision remained, down which I stared at Sayene’s face, wet with effort as she fought to steal my being. I wanted to shout, but I couldn’t open my mouth, couldn’t make a sound. And yet, yet, I felt strength seeping into me. From somewhere I felt power return to my arms and legs. I tugged at the ropes, and they creaked. I was certain if I pulled harder they’d snap like twine.

The voices rose to a crescendo, all coming at the same time.

“Dargahn! Nehmeni! Ourachi!”

“Dargahn! Nehmeni! Ourachi!”

“Dargahn! Nehmeni! Ourachi!”

Silence returned. For a moment there was no movement, but then Elana rushed forward.

“Is it done? Is it finished?”

“He’s protected,” Sayene said flatly. Sweat ran down her face.

“Of course he’s protected,” Elana said. “Every pastry seller in the streets has some protection, and a man like him would have the most of all. That’s why there are three of you here. That’s why you went through all of this, to break his protection.”

“I don’t mean simple wards, Elana,” Sayene said wearily. “Somewhere there’s a Sister of Wisdom who’s actively protecting him. At this very moment she has her hands on his forehead. They won’t stop steel, though. Kill him.”

“She’s a woman of unusual power, Sayene,” Ya’shen mused. “I wonder who—”

“No,” said Elana quietly. “He won’t be killed.”

“Sister,” Eilinn said, “you did agree—”

“No! I want him, and I’ll have him. Alive. You three are supposed to be the most powerful Sisters of Wisdom on this side of the mountains. Break that protection. Find a way.”

“If you’d brought him to us when he was first taken—” said Sayene. “Now, it can be dangerous to try further.”

“If,” suggested Betine, “I brought my two best acolytes, Sisters, really, in all but name, and you brought yours—”

“Could you do it if there were nine of you?” demanded Elana. “Would a simple barbarian beat you then?”

“With nine in the circle,” said Sayene grimly, “we could break any power that exists.”

Sayene’s words kept ringing in my head as the guards took me back to the alcove. With nine in the circle, we could break any power that exists. And the power they wanted to break was the only thing that was keeping me from being broken myself. Thinking of that protection made me think of Mayra. That it was she who had her hands on my forehead I had no doubt. And along with her hands she’d managed somehow to tamper with their spell. As they tried to strip me of will and strength she had managed to reverse their attempt so they actually forced strength on me. It was the only explanation for the way I felt. I was in the first flush of my youth again. Now, if only I could find an opening.

The lamps in the side corridors had been extinguished for the night when two guards came for me. In the darkness of my alcove I smiled.

One of them nudged me with his toe. “On your feet, slave.”

“The queen wants her play pretty,” the other said.

I rose slowly and waited quietly while they unfastened my leg iron. I recognized them now. The same two who’d brought me to the alcove for the first time. It was fitting.

“Come on, slave. Elana won’t wait all night for you. If you make her wait at all she’ll have your hide.”

His eyes found mine in the darkness; remembrance of the questions I’d asked that first day, especially the question about escape, flashed across them. His hand streaked for his sword, and my left hand crushed his throat. The right pulled his sword from its scabbard as he fell. It made a shining fan in the darkness as it rushed toward the other. The second guard’s fingers dropped his sword, and it and his head struck the floor at the same time.

There hadn’t been much noise, but I waited for the guards at the queen’s chamber to come running. Nothing happened.

Quickly I rolled the bodies into the alcove. Neither guard was as tall as I was, but I forced my way into one’s tunic just the same. There might be notice taken of a naked slave running through the halls, but who would pay attention to a guard, even if his tunic was small? Luckily the Lantans wore sandals instead of boots, so the poor fit was still passable, and the helmet was actually too big. As they’d told me the way to escape, they’d also given me the means.

There was little life in the palace at that hour, save for servants and slaves hurrying on assigned chores, preparing for tomorrow. They had no time nor any desire to question anyone, certainly not a guard. They lowered their heads when they saw me and scurried by, eyes on the floor.

The few other guards, free assistants to Ara and the like, gave more problems. They appeared suddenly from side corridors as I passed, or opened doors behind me. It was as much as I could do at those times to keep walking calmly as if I had a right to be there and a right to go where I was headed. The borrowed tunic began to sweat through.

The second corridor that crossed the one of my alcove after the one that leads to the queen’s chambers, the guard had said. Then go to the left. At the first stairs go down three flights.

Those first stairs were wide, sweeping things of polished white stone. They looked more like a main passageway than an escape route. Had the guard thought to give me a false route?

I’d not time to ponder it, and I couldn’t afford to take the guard’s route as false until I was certain. At the bottom of the third flight I turned in the direction I’d been heading above. Was it false? The door at the end was the same massive door that could be found on any of a thousand palace chambers. Was it the outer wall on the other side, or a guardroom? I drew the guard’s sword, kissed the blade, and threw open the door.

Moonlight streamed through, and I could see the parapet around the palace. I dashed through and pulled the door shut behind me. Not until then did I permit myself the sigh of relief I needed.

Loewin, Mondra and Wilaf were in the sky. Together they gave light to see clearly, but their pattern on that night cast strange triple shadows that shifted and moved. It was a good night for sneaking from shadow to shadow, but in the open space of the square those shadows twisting around me would only draw the attention of the guards. I needed another way to leave.

I took advantage of those shadows on the wall, though. If there was a way out other than dropping over the side to the square below, it would be somewhere on that outer wall.

I had covered nearly a quarter of the wall, careful as a poacher to avoid guards, when I moved out of the darkness and from the corner of my eye saw a man-shape. I froze, and then realized the other hadn’t moved. And he seemed to be straddling a strong cylinder as if it was a horse.

The moons continued their courses, and the clouds shifted, and as the patterns of light on the walltop changed, I saw that he was naked, and his hands were bound behind him. He sat there, head on his chest, unmoving, and as the light played across him, I recognized him.

“Hulugai,” I murmured, and rushed to him. “Hulugai, I thought you all were dead. Where are the others?”

He raised his head, and I skidded to a halt. His face was beaten and bruised, his eyes near swollen shut, and a rope of blood hung from the corner of his mouth. Now that I was close I could see other marks on his body, too, whip marks, slashes and gashes as if he’d been savaged by some beast.

“The rest are dead,” he said faintly, “and better I was, too.”

“Nonsense,” I said. “I’ll get you free, and then we’ll both—”

I had him half lifted off, and he muted a shriek that even so chilled the bones in me. I gave a moan of my own when I saw the spiked iron bar below him. He’d been impaled.

“S-set me down, my lord.”

Gently as I was able I lowered him, and tried to close my ears to the cries he couldn’t stifle. “I’m sorry, Hulugai. I’ve much to answer for, bringing you to this.”

“Nothing to answer for, my lord,” he breathed. “My right to ride with you. My right to die for you. I’m not a fat merchant, to die in bed.”

“Who ordered this? Who ordered it, Hulugai?”

“Sayene, the Sister of Wisdom. For a long time they kept us locked away, hidden, I think. When Sayene found us, a tenday ago, she was furious about us being there.” He tried to laugh and choked instead. “She was so mad I thought she’d have a seizure. She questioned each of us. Used a truth-spell. She didn’t find what she wanted, my lord. Whatever it was, she didn’t find it.”

“I know, Hulugai, I know. Rest now.”

Conan the Unconquered

Conan the Unconquered Conan the Triumphant

Conan the Triumphant The Eye of the World

The Eye of the World The Great Hunt

The Great Hunt Conan the Victorious

Conan the Victorious The Dragon Reborn

The Dragon Reborn The Fires of Heaven

The Fires of Heaven Winter's Heart

Winter's Heart Lord of Chaos

Lord of Chaos The Shadow Rising

The Shadow Rising Conan the Defender

Conan the Defender The Strike at Shayol Ghul

The Strike at Shayol Ghul The Path of Daggers

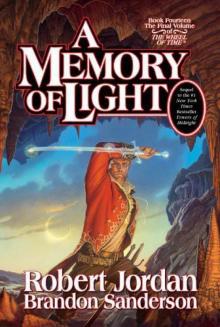

The Path of Daggers A Memory of Light

A Memory of Light Knife of Dreams

Knife of Dreams Crossroads of Twilight

Crossroads of Twilight Conan the Invincible

Conan the Invincible The Gathering Storm

The Gathering Storm Warrior of the Altaii

Warrior of the Altaii A Crown of Swords

A Crown of Swords The Wheel of Time

The Wheel of Time Towers of Midnight

Towers of Midnight Conan Chronicles 2

Conan Chronicles 2 Conan the Magnificent

Conan the Magnificent New Spring

New Spring What the Storm Means

What the Storm Means A Memory of Light twot-14

A Memory of Light twot-14 New Spring: The Novel

New Spring: The Novel Towers of midnight wot-13

Towers of midnight wot-13 A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14

A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14 A Crown of Swords twot-7

A Crown of Swords twot-7 Lord of Chaos twot-6

Lord of Chaos twot-6 The Great Hunt twot-2

The Great Hunt twot-2 The Shadow Rising twot-4

The Shadow Rising twot-4![Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/03/wheel_of_time-11_knife_of_dreams_preview.jpg) Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams

Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams The Dragon Reborn twot-3

The Dragon Reborn twot-3 The Wheel of Time Companion

The Wheel of Time Companion The Fires of Heaven twot-5

The Fires of Heaven twot-5 Prologue to Towers of Midnight

Prologue to Towers of Midnight The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8

The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8 The Path of Daggers twot-8

The Path of Daggers twot-8 By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light

By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light Crossroads of Twilight twot-10

Crossroads of Twilight twot-10 The Gathering Storm twot-12

The Gathering Storm twot-12 Winter's Heart twot-9

Winter's Heart twot-9 Knife of Dreams twot-11

Knife of Dreams twot-11 New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)

New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)