- Home

- Robert Jordan

Conan the Victorious Page 14

Conan the Victorious Read online

Page 14

Naipal sighed irritably. The treaty with Turan followed the simple principles he had led Karim Singh to believe were his own. To seize the throne at Bhandarkar’s death required a land in turmoil. Outside enemies tended to unify a country. Therefore all nations that might threaten Vendhya—Turan, Iranistan, the nations and city-states of Khitai and Uttara Koru and Kambuja—must be placated, made to feel neither threatened by nor threatening toward Vendhya. The wizard’s preferred method was the manipulation of people in key positions, supplemented by sorcery where needed. It was Karim Singh who thought in terms of treaties. Still, the journey to Turan had kept him safely out of Naipal’s way for a time.

“Excellency, if Yildiz would not sign, it is of no import. Assuredly, even if Bhandarkar holds the failure against Your Excellency, he has no time to—”

“Listen to me, fool!” Karim Singh’s eyes bulged hysterically. “The treaty was signed! And perhaps within hours of that signing the High Admiral of Turan was dead! At the hands of Vendhyan assassins! Who else but Bhandarkar himself would dare such a thing? And if it is indeed him, then what game does he play? Do we move against him unseen, or does he merely toy with us?”

Sweat dampened Naipal’s palms as he listened, but he would not wipe them while the other could see. His eyes flickered to the ivory chest. An army? With wizards perhaps? But how could such be mobilized without his knowing? “Bhandarkar cannot know,” he said at last. “Is Your Excellency sure of all of the facts? Stories often become distorted.”

“Kandar was convinced. And this Patil, who told him, is no man for intrigue. Why, he is as devious as a newborn infant.”

“Describe…this Patil to me,” the wizard said softly.

Karim Singh frowned. “A barbarian. A pale-skinned giant with the eyes of a pan-kur. Where are you going? Naipal!”

Before the description was finished, the wizard leaped to the ivory chest. He threw back the lid, brushed aside the silken coverings and stared at exactly what he had seen the night before, a vast array of fires in the night. Not an army. A huge caravan. So many pieces suddenly fell into place, yet for every answer there was a new question. He became aware again of Karim Singh’s shouting.

“Naipal! Katar take you! Where are you? Return instantly or by Asura…” The wizard moved again in front of the mirror that contained Karim Singh’s now-apoplectic visage. “Just in time to save your head! How dare you leave like that, without so much as craving permission or a word of explanation? I will not tolerate such—”

“Excellency. Please, Your Excellency must listen. This man calling himself Patil, this barbarian giant with the eyes of a pan-kur”—in spite of himself, Naipal shuddered at that; could it be an omen, or worse?—“he must die, and everyone with him. Tonight, Excellency.”

“Why?” Karim Singh demanded.

“His description,” the mage improvised. “Various divinations have brought it to me that a man of that description can bring ruin to all our plans. And as well there is another threat to us in the same caravan with Your Excellency, a threat of which I learned only a short time ago. There is a party of Vendhyan merchants. Their leader is a man called Sabah, though he may use another name. They have pack mules rather than camels, bearing what will appear to be bales of silk.”

“I suppose these men must die as well,” Karim Singh said and Naipal nodded.

“Your Excellency understands well.” Commands had been given and apparently not obeyed. Naipal did not tolerate failure.

“Again, why?”

“The arts of divination are uncertain as to details, Excellency. All that I can say for certain is that every day, every hour that these men live, is a threat to Your Excellency’s ascension to the throne.” The wizard paused, choosing his words. “There is one other matter, Excellency. Within what appear to be the bales of silk of the Vendhyan merchants will be chests sealed with lead seals. These chests must be brought to me with the seals unbroken. And I must add that the last is more important to Your Excellency’s gaining the throne than all the rest, than all we have done so far. The chests must be brought to me with the seals unbroken.”

“My gaining the throne,” Karim Singh said flatly, “depends on chests being brought to you? Chests that are with the very caravan in which I travel? Chests of which you knew nothing until a short time ago?”

“Before Asura, it is so,” Naipal replied. “May my soul be forfeit.” It was an easy oath to make; that forfeit had been made long since.

“Very well then. The men will be dead before the sun rises. And the chests will be brought to you. Peace be with you.” The silver bell chimed in sympathy with the silver bell in the wazam’s tent so far away, and the image in the mirror leaped and was that of Naipal.

“And peace be with you, most excellent of fools,” the wizard muttered.

He looked at his palms. The sweat was still there. So many new questions, but death would provide all the answers he needed. Smiling, he wiped his hands on his robes.

CHAPTER XIV

Absolute darkness was pushed back from the night-swathed encampment by hundreds of campfires scattered among a thousand tents. Many of those tents glowed with the light of lamps within, casting moving, mysterious shadows on walls, whether silk or cotton, made less than opaque. The thrum of citherns floated in the air, and the smell of cinnamon and saffron from meals not long consumed.

Conan approached Vyndra’s tent with an uncertainty he was not used to. All during the day’s march he had avoided her, and if that consisted mainly in staying with Kang Hou’s camels rather than seeking her out, it had not been so easily done as it sounded. It was possible she wanted him only as an oddity for her noble friends in Ayodhya, a strange-eyed barbarian at which to gawk, but on the other hand, a woman did not look at an oddity coquettishly through lowered lashes. In any case, she was beautiful, he was young, and therefore he had come as she asked.

Ducking through the tent’s entrance flap, he found himself staring Alyna in the eyes, which was still all he could see of her for thick veils and heavy robes. “Your mistress,” he began and cut off as a flash of murderous rage flickered through the woman’s eyes.

As quickly as it appeared, though, it was gone, and she bowed him deeper into the tent, which, though smaller than Karim Singh’s, was divided within in much the same fashion by silken hangings.

In a central chamber floored with exquisite Vendhyan carpets and lit by golden lamps, Vyndra stood awaiting him. “You came, Patil. I am glad.”

Conan clamped his teeth firmly to keep from gaping. Gold and rubies and emeralds still bedecked her, but the robes she had worn earlier were now replaced by layers of purest gossamer. She was covered from ankles to neck, yet her position in front of a lamp cast shadows of tantalizing mystery on rounded surfaces, and the scent of jasmine floating from her seemed the very distillation of wickedness.

“If this were Turan,” he said when he found his tongue, “or Zamora or Nemedia, and there were two women in a room dressed as the two of you, it would be Alyna who was free, and you who were slave. To a man, without doubt, and the delight of his eye.”

Vyndra smiled, touching a finger to her lips. “How foolish of those women to let their slaves outshine them. But if you wish to see Alyna, I will have her dance for you. I have no other dancing girls with me, I fear. Unlike Karim Singh and the other men, I do not find them a necessity.”

“I would much rather see you dance,” he told her, and she laughed low in her throat.

“That is something no man will ever see.” Yet she twined her arms above her head and stretched in a motion so supple it cried dancer, and one that dried Conan’s throat. That fabric was more than merely sheer when drawn tight.

“If I could have some wine?” he asked hoarsely.

“Of course. Wine, Alyna, and dates. But sit, Patil. Rest yourself.”

She pressed him down onto piled cushions of silk and velvet. He was not sure of exactly how she managed this since she had to reach up to put her small han

ds on his shoulders, but he suspected the perfume had something to do with it.

He tried to put his arms around her then, while she bent over him so enticingly, but she slipped away like an eel and reclined on the cushions just an arm’s length away. He settled for accepting a goblet of perfumed wine from Alyna. The cup was as heavy as the one in which the wazam had given him wine, though instead of amethysts, it was studded with coral beads.

“Vendhya seems to be a rich land,” he said after he had drunk, “though I’ve not been there yet to see it.”

“It is,” Vyndra said. “And what else do you know of Vendhya before you have been there?”

“Vendhyans make carpets,” he said, slapping the one beneath the cushions, “and they perfume their wine and their women alike.”

“What else?” she giggled.

“Women from the purdhana are shamed by baring their faces but not by baring anything else.” That brought an outright laugh, though the edges of a blush showed about Alyna’s veil. Conan liked Vyndra’s laughter, but he was already tired of the sport. “Beyond that, Vendhya seems to be famous for spies and assassins.”

Both women gasped as one, and Vyndra’s face paled. “I lost my father to the Katari. As did Alyna.”

“The Katari?”

“The assassins for which Vendhya is so famous. You mean you did not even know the name?” Vyndra shook her head and shuddered. “They kill, sometimes for gold, sometimes for whim it seems, but always the death is dedicated to the vile goddess Katar.”

“That name I have heard,” he said, “somewhere.”

Vyndra sniffed. “No doubt on the lips of a man. It is a favorite oath of Vendhyan men. No woman would be so foolish as to call on one dedicated to endless death and carnage.”

She was clearly shaken, and he could sense her withdrawing into herself. Frantically he sought another topic, one fit for a woman’s ears. One of her poets would no doubt compose a verse on the spot, he thought bitterly, but all the verse he knew was set to music, and most of it would made a trull blush.

“A man of your country did say something out of the ordinary to me today,” he said slowly, and latched on to the one remark out of several that would bear repeating. “He thought my eyes marked me as demon-spawn. A pan-kur, he called it. You obviously do not believe it, else you’d have run screaming rather than inviting me to drink your wine.”

“I might believe it,” she said, “if I had not talked to learned men who told me of far-off lands where the men are all giants with eyes like sapphires. And I rarely run screaming from anything.” A small smile had returned to play on her lips. “Of course, if you actually claim to be a pan-kur, I would never doubt the man who calls himself Patil.”

Conan flushed slightly. Everyone seemed to know the name was not his, but he could not bring himself to say that he had lied about it. “I have fought demons,” he said, “but I am none of their breed.”

“You have fought demons?” Vyndra exclaimed. “Truly? I saw demons once, a score of them, but I cannot imagine anyone actually fighting one, no matter what the legends say.”

“You saw a score of demons?” Despite his own experience seemingly to the contrary, Conan was aware that demons—and wizards, for that matter—were not so thick on the ground as most people imagined. It was just that he had bad luck in the matter, though Hordo insisted it was a curse. “A score in one place?”

Vyndra’s dark eyes flashed. “You do not believe me? Many others were there. Five years ago in the palace of King Bhandarkar, he who was then the court wizard, Zail Bal, was carried off in full view of scores of people. The demons were rajaie, which drink the life from their victims. You see, I know whereof I speak.”

“Did I say I did not believe you?” Conan asked. He would believe in twenty demons in one place—much less anyone escaping alive from that place—when he saw it, but he hoped devoutly that his luck was never quite that bad.

A small crease appeared between Vyndra’s brows, as though she doubted his sincerity. “If you have truly fought demons—and you see I do not question your claim—then you must certainly stay at my palace in Ayodhya. Why, perhaps even Naipal would come to meet a man who has fought demons. What a triumph that would be!”

It might have sounded promising, he thought ruefully, if not for this other man. “Do you wish me there, or this Naipal?”

“I want both of you, of course. Think of the wonderment. You, a huge warrior, obviously from a land shrouded in distance and mystery, a fighter against demons. He, the court wizard of Vendhya, the—”

“A wizard,” Conan breathed heavily. Hordo would believe he had done this apurpose, or else he would mutter about the curse.

“I said that,” Vyndra said. “He is the most mysterious man in Vendhya. No more than a handful other than King Bhandarkar, and perhaps Karim Singh, know his face. Women have arranged assignations with him merely in the hope they might be able to say they could recognize him.”

“I have never met the man,” he said, “nor intend to, yet I do not like him.”

Her laugh was low and wicked. “He keeps the assignations, too, with those women pretty enough. They are gone for days and return on the point of exhaustion with stories of passion beyond belief, but when they are asked of his features, they grow vague. The visage they describe could belong to any handsome man. Still, the transports of rapture they speak of are such that I myself have considered—”

With a curse Conan hurled the golden goblet aside. Vyndra squeaked as he pounced, catching her face between his hands. “I do not want you to attract some sorcerer,” he told her heatedly. “I do not want you because you are from a country distant from mine or because you would seem strange to the people of my land. I want you because you are a beautiful woman and you make my blood burn.” There was invitation on her face and when he kissed her, she tangled her hands in his hair as though it were she who held him, not the reverse.

When at last she snuggled against his chest with a sigh, there was a mischevious twinkle in her big dark eyes, and small white teeth indented her full lower lip. “Do you intend to take me now?” she asked softly and then added as he growled in his throat, “With Alyna watching?”

Conan did not take his eyes from her face. “She is still here?”

“Alyna is faithful to me in her fashion and rarely leaves my side.”

“And you do not intend to send her away.” It was not a question.

“Would you have me separated from my faithful tirewoman?” Vyndra asked with a wide-eyed smile.

Clearing his throat, Conan got to his feet. Alyna was there, bright eyes glinting with amusement above her veil. “I have half a mind,” he said conversationally, “to switch both your rumps till you have to be tied across your saddles like bolts of silk. Instead, I think I will see if there is an honest trull in this caravan, for your games bore me.”

He stalked out on that, thinking he had quieted her, but laughing words followed him before he let the tent flap fall. “You are a violent man, O one who calls himself Patil. You will be a wonderment to my friends.”

CHAPTER XV

There were panderers on the outskirts of the encampment, as Conan had known there would be in a caravan so large and going so far. Two of them. Karim Singh might have his own women along, as would the Vendhyan noblemen and even many of the merchants, but for the rest—for guards and camel drivers and mule handlers—from Khawarism to Secunderam was a long way without a woman. Except for the panderers.

They had set out tables made of planks laid on barrels before their tents, with casks to sit on and drink while a man waited his turn for the use of the tents. Cheap wine they gave away to those who bought their other merchandise, sour wine served by sweet women, slender jades and voluptuous trulls, tall wenches and short. Soft, willing flesh. If the gilded brass girdles low on their hips and their strips of diaphanous silk were more than a purdhana dancer wore, all could be removed for a coin, for women were the goods sold here.

A

nd yet, Conan realized, it was not a woman he wanted. He sat on an upended keg before the second panderer’s tents, a leathern jack of thin wine in his fist, a slender wench wiggling on his knee as she bit at his neck with small white teeth. He could not pretend disinterest in her, but she seemed a distraction, if a pleasant one. A buxom jade at the first panderer’s tent had been the same. Though he was not yet twenty, he had long since learned to curb his anger when need be, but on that day he had held it in check with Karim Singh and lashed it down with Kandar. And then there had been Vyndra. Now he wanted to loose the rage, to strike out at something. He wanted one of the other men fondling a woman to challenge him for the doxy on his lap, or two, or five. Hammering fists, even bloody steel, would drain the anger coiled in his belly like a serpent dripping venom from its fangs.

The slender trull snuggled against him contentedly as he stood with her in his arms, then stared at him in consternation when he plopped her bottom onto the keg. “I am not a Vendhyan,” he told her, dropping coins in her hands. “I do not take out my anger on others than those who have earned it.” Her look was one of total uncomprehension, but he spoke for his own benefit as much as hers.

The raucous laughter of the panderers’ tents followed him into the encampment. Many of the merchants’ tents were darkened now, and silence lay even on the picket lines of animals behind each, though the thin sounds of zither and flute, cithern and tambor, drifted from the nobles’ portion of the camp. Sleep, he thought. Sleep, then journey on the morrow, then sleep again and journey again. The antidote would be found in Vendhya, and the answers he sought would come, but he would dissipate the tightness of anger with sleep.

The fire burned low in front of the lone tent shared by Kang Hou and his nieces. A Khitan servant poking the embers was all that moved among the blanket-wrapped shapes of smugglers scattered about the merchant’s tent. But Conan stopped short of the dim light of that fire, a jangling in the back of his head that he recognized as a warning that something was wrong.

Conan the Unconquered

Conan the Unconquered Conan the Triumphant

Conan the Triumphant The Eye of the World

The Eye of the World The Great Hunt

The Great Hunt Conan the Victorious

Conan the Victorious The Dragon Reborn

The Dragon Reborn The Fires of Heaven

The Fires of Heaven Winter's Heart

Winter's Heart Lord of Chaos

Lord of Chaos The Shadow Rising

The Shadow Rising Conan the Defender

Conan the Defender The Strike at Shayol Ghul

The Strike at Shayol Ghul The Path of Daggers

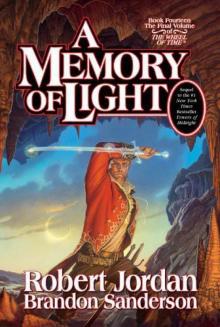

The Path of Daggers A Memory of Light

A Memory of Light Knife of Dreams

Knife of Dreams Crossroads of Twilight

Crossroads of Twilight Conan the Invincible

Conan the Invincible The Gathering Storm

The Gathering Storm Warrior of the Altaii

Warrior of the Altaii A Crown of Swords

A Crown of Swords The Wheel of Time

The Wheel of Time Towers of Midnight

Towers of Midnight Conan Chronicles 2

Conan Chronicles 2 Conan the Magnificent

Conan the Magnificent New Spring

New Spring What the Storm Means

What the Storm Means A Memory of Light twot-14

A Memory of Light twot-14 New Spring: The Novel

New Spring: The Novel Towers of midnight wot-13

Towers of midnight wot-13 A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14

A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14 A Crown of Swords twot-7

A Crown of Swords twot-7 Lord of Chaos twot-6

Lord of Chaos twot-6 The Great Hunt twot-2

The Great Hunt twot-2 The Shadow Rising twot-4

The Shadow Rising twot-4![Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/03/wheel_of_time-11_knife_of_dreams_preview.jpg) Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams

Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams The Dragon Reborn twot-3

The Dragon Reborn twot-3 The Wheel of Time Companion

The Wheel of Time Companion The Fires of Heaven twot-5

The Fires of Heaven twot-5 Prologue to Towers of Midnight

Prologue to Towers of Midnight The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8

The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8 The Path of Daggers twot-8

The Path of Daggers twot-8 By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light

By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light Crossroads of Twilight twot-10

Crossroads of Twilight twot-10 The Gathering Storm twot-12

The Gathering Storm twot-12 Winter's Heart twot-9

Winter's Heart twot-9 Knife of Dreams twot-11

Knife of Dreams twot-11 New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)

New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)