- Home

- Robert Jordan

Warrior of the Altaii Page 14

Warrior of the Altaii Read online

Page 14

“And the Lantans,” I said, “did they touch the sky-stone when they spoke?”

“After the oaths they swore, who would ask them to?”

“Then they lied, and knew they lied. The oaths they never meant to keep were only meant to keep them from having to touch the sky-stone and have their hands burned off by their lies. It could be no other way.”

“My lord, what happened there in the city? How could they take you?”

“They were waiting for us on the rooftops over the Street of Five Bells, with chain nets. Even though we went early, they knew we were coming.” That struck me all of a sudden and I repeated it. “Even though we went early, they knew we were coming. Yes. It was so. They took us like fish from a stream. Only Brion gained glory from it. They paid a ferryman’s fee for him fit for a king. They imprisoned us, but I didn’t know what happened to the others until I’d escaped. They tortured them, Bartu. Not for a reason, but for the sport of it. Then they impaled them.”

“Once, my lord, you spoke of finding out how many lances it would take to tear down the walls of Lanta. Do you know the number, yet?”

“I know, Bartu. I know.”

XVII

A BELL NOTE

At the tents many called laughingly to Bartu to ask if he was capturing beggars these days. No one knew me, and the comments grew louder the deeper into the tents we rode. Even unbranded youths snickered behind their hands. I saw some thoughtful stares, though. Soon someone would realize who I was, and the laugh would be on the laughers.

Elspeth, Sara and Elnora were working in front of my tent when I swung down. They eyed me with distaste.

“Why are you bringing him here, Bartu?” Sara asked.

“Bring me the tub,” I said, “and water. I want a bath before I get used to this smell.”

They stared at me with their mouths open. Suddenly it struck them that it was indeed I who masqueraded in a beard and the smells of slop tubs. While they were laboring with the tub, Orne walked in.

“Lord Wulfgar.” He started to throw his arms around me, and stopped with them spread wide. His nose twitched.

“I’m taking a bath,” I said. “They’re getting the tub, now.”

“I’ll help them, my lord.”

With his help the girls wrestled the tub into the tent. Then they ran for water, and he sat to talk. I dropped the guard tunic on the ground.

“That’s to be burned.”

“And that so-called horse, my lord?”

“Turn it loose with the herds.”

“My lord,” he protested.

“It’s a gelding, Orne, so there’s no worry for the bloodlines. And it carried me away from Lanta. It also has more brains than its former driver. He walked back to Lanta and his chains.” They had finished filling the tub, and I settled myself into it, slowly. “Orne, tell Mayra I’ll be to her as soon as I’m clean. She’d not have thanked me for coming as I was.”

“Yes, Lord Wulfgar.”

He went on his way, and I relaxed as Elnora and Sara scrubbed away the stink. They wore the kisu, long panels of clinging, opaque silk that hung below the knees in front and back and were fastened at the waist with a belt. Elspeth stood to the side not looking at me as I bathed.

“How is your training going, Elspeth?” I asked.

“It’s going fine,” she said through pursed lips.

I smiled. Her spirit wasn’t broken in my absence. “You’re playing a game, Elspeth. Games can be dangerous.”

“No games, then. It’s not fair. That’s how my training is. Not fair. I have to read, not only your language, but others I’ve never heard of, not because I might want to, but so I can read to you, or recite poems to you. And for some reason I have to learn to cook dishes in twenty different styles, and dance dances from a dozen countries, and sing. Talva beats me because I don’t have a good voice. I can’t make myself have a good voice. Why does she have to beat me for something I can’t change?” Her eyes closed and her head fell forward. “And that’s the way it’s changing me. I complain because she beats me for something I can’t change. Not about being beaten, but because it’s for something I can’t change. It’s not fair, not fair.”

“Your world is always fair.” I didn’t make it a question, and she just straightened and looked at me without speaking. I don’t think she would have or could have answered it anyway. “There’s no fairness to worlds. Fairness is a thing created by men. It doesn’t exist. It isn’t the same in different cities, or among different people. How can fairness be the same thing in two different worlds? In your world you were a scholar, in this one you’re nothing. In this world I’m a warrior, but if I went to yours, I might be a beggar.”

It didn’t make a mark on her attitude. I could see that from the stubborn cast to her jaw. So I tried another way. “Where you were found when you first came to this world, you could have expected to live to sunset at best. With no water, no food, no knowledge of the land, and above all with no way to protect yourself from anything from a fanghorn to a kes hive, you were dead.”

I was reaching for the toweling Sara held when Elspeth said, “I have an answer to your problem.”

She said it so softly that it didn’t register on my mind at first. When it did I whirled around with the toweling forgotten around my shoulders.

“The problem? You’ve—” I jerked my head toward the tent flaps. “Sara, Elnora, wait outside.” When they’d gone I turned my attention back to Elspeth. She was still kneeling by the tub, frowning at the floor, a slight pout on her lips. “The problem,” I said.

“It wasn’t until I learned exactly what your people’s problem was that I saw the solution. The weather on the Plain gets worse every year, now, and has for some years past. There’s less water every year, and less forage for your herds. It’s hotter in the summers, and the winters are colder. And that makes the fanghorns multiply. They breed in the summers, and give birth during the winters in hibernation. The colder winters mean they hibernate longer, and the young have gotten larger by the time they come out in the spring, so more and more of them are able to survive.”

“So far,” I said dryly, “you’ve told me a great deal that I already know.”

She took a deep breath and went on. “There are many peoples who’ve faced the same problem, or the same sort of problem, and those who solved it did it in the same basic way. I’ve studied it time and time again.”

“You mean you knew this all the time? You knew the answer the first day I found you?”

“That’s right,” she said angrily, “I knew it. But you never told me what the problem was. I never knew I had your answers. You just kept on bullying and browbeating me like I was—”

“The answers.” I forced myself to back away, to stop hovering over her. “You’ve gone a long way with this. Now, how did those people you studied solve their problem?”

“You won’t like it,” she said. I just waited. “These people, when the land changed so their old lifestyle wouldn’t work anymore, they changed it. The ones like you settled down, planted crops, built villages, dug wells for irrigation. They stopped being nomadic herders and became farmers.”

“Farmers.” I put as much venom into the word as I could muster. “You suggest the Altaii become farmers? We’re not grubbers in the dirt. We live by our herds, and by our swords. By our swords most of all. If we have to die, we’ll die as what we are, not like those northern dirtmen, selling their roots and pulling their forelocks to everyone who frowns at them.”

“But you have to change, or that’s exactly what will happen. You’ll all die. But if you do change, it doesn’t have to be that bad. Your villages could become cities, in time. One day they might be as big as Lanta.”

The name hung there in the air like a bell note.

“Lanta,” I breathed, and it was as if the bell had been brushed again.

“M-my lord, I don’t understand,” she said, but she could feel it in the air too.

“If we take Lanta, we won’t ha

ve to wait for our villages to grow. Lanta could serve as a center for the entire Altaii nation.”

“No. Wulfgar.”

“There are lands to the east of Lanta that could support our herds, all of them, for countless years to come. I said we might have to take Lanta, but now we have a hundredfold reason to do it.”

“I didn’t tell you this to start you off on some war of conquest.”

“Elspeth, if you’ll feel better about it, the Lantans moved against us first. At this moment they’re plotting with the Morassa to destroy us. If we don’t destroy them first, the Plain won’t have a chance to kill us. We will be dead already.”

“Violence doesn’t excuse violence, Wulfgar. Conquering lands and keeping them is wrong.”

“Conquering lands and not keeping them is stupid,” I said. Hurriedly I got into tunic, trousers and boots. “Hand me my sword belt and come with me. We’re going to see Mayra. She can tell me if taking Lanta is what I must do or not do.”

XVIII

WOMEN’S JUSTICE

Mayra was waiting for me, impatiently, which wasn’t usual for her. She barely waited until I was seated, and Elspeth kneeling off to one side, before she spoke. With the first word, I remembered Bartu’s words about her tongue being a weapon.

“It’s said, Lord Wulfgar, that men think with their manhood instead of their brains. I’m not sure you used even that. You not only risked your life needlessly, you risked the future of the Altaii. You nearly allowed your spirit and will to be made into a pendant for the queens to play with.”

“I know, Mayra,” I said soothingly. Elspeth and Mayra’s acolytes were smirking, but I needed her goodwill at the moment more than I needed to stop some girls from giggling. “And I know that I owe my survival of that attempt to you. I just don’t know how you did it.”

“A simple spell,” she said disparagingly. “Once I knew you meant to go ahead with that foolishness, I took a hair from your shaving and a tunic still wet with your sweat and made a simple bond between us. Then I could tell what happened, but vaguely, as if through a silk screen. I couldn’t do anything about physical dangers, but when they tried spells, then I could give aid. They were powerful, Wulfgar. I have not seen that much power in a long time. Who were they?”

At least the formality was gone. I wasn’t Lord Wulfgar to her anymore. “Sayene was there, and a woman called Ya’shen, and one who looked like somebody’s grandmother. Her name was Betine. I’ve something to ask, Mayra.”

She didn’t hear me. “Ya’shen and Betine as well as Sayene. I wonder how the Twin Thrones managed to get those three together? And Betine is no one’s grandmother, unless it’s a demon of some sort. She’s as evil as Loewin’s breath. Ya’shen is as bad, and I fear Sayene has become the worst of them all. There’s darkness there, darkness and power together, and I don’t know if I can gather enough strength among the Altaii Sisters of Wisdom to defeat them. There aren’t many of us with that much power.” She seemed to become aware of me again. “Your question, Wulfgar?”

Quickly I laid out what Elspeth had told me, and what I had made of her words. “Is it true, Mayra? Is it a true way?”

Mayra looked at Elspeth and shook her head. “The odds are very long, Wulfgar. Even Basrath—” But she took out her bag containing the rune-bones.

Three times presented to the sky, and three times to the earth, the bones were rolled. Mayra sucked her breath over her teeth. Quickly she rolled them again. This time she was clearly surprised. For a moment she waited, as if afraid to see what would be said the third time, but the rune-bones were tossed for the third time. Mayra stared at them as if she wasn’t sure what she saw. Twice she reached out to touch them, and twice drew back.

“In the first throw the same pattern duplicated three times. That’s unusual. On the second the pattern was there again, six times. On the third throw that same pattern repeated nine times. I’ve never seen a progression like that. Never.”

“The pattern, Mayra?” I asked. “What was the pattern?”

“Lanta must fall, and to your hand. That is specific. It must be your hand which opens the way for the city to fall. If it does, then the Altaii star rises high, and the Lantan star fades. If not, it is the Altaii star which fades and disappears.”

“First I must preserve my life as if it was a jewel. Now I must open the way to Lanta with my own hand.” I rubbed at my face and let my head rest in my hands. “Do the rune-bones give any guide as to how I’m to do that?” I asked wearily. Something brushed lightly at my shoulder. Elspeth had moved to kneel beside me. She didn’t look at me, but her hand rested on my shoulder.

“There is something,” Mayra said softly. “The rune-bones indicate, Wulfgar. They don’t tell things clearly. They have to be interpreted, and this one I don’t know how to interpret. It seems opposed to the other symbols, and it occurs in minor case, but three times din, the minor-case salvation, has rested on top of silte, the minor-case hunt. It might mean salvation rests on the hunt. There are no symbols close enough to the configuration to modify it.”

“Hunt? What hunt, Mayra? There’s no hunting worth the name in three days’ ride of here, except for fanghorns, and there’s nothing to do with one of those except kill it.”

“The silte symbol is the hunting bow, the longbow. It could mean salvation rests on the bow. That sounds more likely for war, at any rate.”

The hunting bow is just that, a bow used for the hunt. It’s longer than a man is tall, too long to use on a horse, but for hunting animals that run when a mounted man is a thousand paces away, it works well. The stalk is made on foot, and then a shaft can be put in an antelope at four hundred paces, or a ku at twice that.

“I once made a joke,” I said, “about tearing the walls of Lanta down with Altaii lances. The longbow seems even less suited to the job.”

“That’s not so,” said Elspeth. “In my world’s history, they trained men to use the longbow. With its superior range and power against the shorter bow of mounted cavalry, and the spear and sword of infantry, it’s a powerful weapon.”

“I can’t help you with that, Wulfgar,” Mayra said, “but perhaps I can stimulate your thinking.”

She sounded angry suddenly, angry and vengeful and in some fashion satisfied. She motioned and two of her acolytes struggled forward with a sack between them. Something inside wiggled. They set it down and slit it open. There was a woman inside, a woman cruelly arched and bound. Elspeth gasped at the sight of her, and her fingers dug into my shoulder. The woman’s feet had been pulled up almost to her shoulders, and her wrists were tied to her knees. There was a large gag in her mouth. She looked around wildly when the sack was cut open, and when she saw me, she began to cry. It was Mirim.

“Orne found her,” Mayra said. “I told him I’d shrivel his tongue if he spoke of it to anyone, and I see he took that to include you. Don’t blame him, Wulfgar. I meant what I said, and he knew it.”

“I don’t blame any man for failing to cross a Sister of Wisdom, Mayra, but what’s so important about a runaway slave?”

Mayra fixed the bound girl with her eye, and Mirim began to sweat. “He found her near the walls of Lanta, Wulfgar. She panicked when he caught her, babbled wildly. After he heard some of the babbling he brought her to me without telling anyone else. Probably the smartest thing he’s ever done.”

“What did she babble?” I asked quietly, but Mirim flinched as if I’d shouted.

“Nothing, once she was here. Under a truth-spell, though, she said some interesting things. She was sent to Lanta, to ask at the gates for a man named Ara. They had orders to bring Altaii slaves who asked for that man to him.”

“I know the name,” I bit off.

“She was to tell him where we went next, when we began our march, and how long we expected to stay in the new camp. She also said that other girls had been sent on the same errand, to help the Lantans know where we went and when.”

“Sent,” I said. “You said that twice. Sent by wh

o?”

“Talva.”

It didn’t really surprise me. When she’d said that other girls had been sent I’d remembered the string of runaway slaves, with only Talva to link them. “The Lantans knew I was coming, Mayra. They were waiting for me. To me that shouts betrayal, and right now Talva seems a good suspect.”

“Perhaps. As much as I hate to say it, Talva’s treason could be no more than letting the caravans know how to avoid us. We’ll see, though.”

She spoke quietly to one of the acolytes. The young woman ran off and returned in a moment with the tripod and box that Mayra had brought out so long ago. She set the tripod while Mayra took the silver bowl, with its symbolic markings, from the box. When all was in place, she went through the ritual with the oil and the powders. An image appeared in the window of the bowl, and she beckoned me.

“Does it mean something to you?”

All the bowl showed was a bird flying, a falcon. “Nothing,” I said.

“I began with the belief that a message was carried to Lanta to betray you. It happened, it appears, and this bird carried the message. Possibly—” She spoke in the ear of an acolyte. The girl went to Mayra’s chests and returned with a small bell. “Briskly now, child, as the powders fall.”

Mayra dropped a pinch of some powder into the image. It flared, and as it flared, the acolyte struck the bell twice, rapidly. Again a pinch of powder fell, and the bell again rang twice. For the third time the bowl flared beneath the powder, the bell rang, and its last tone went on and on. Mayra put a hand to it to stop the sound. “Look.”

In the bowl’s window Talva took a falcon from the cage behind her tent. She carried it on a padded glove to a perch, and put it there while she fastened a small cylinder to its leg. Then she took it up again and cast it into the sky. It disappeared rapidly, as if certain of its destination.

“That bird carried the message,” Mayra said.

The growl started deep in my chest. It built in my throat, and I could feel my lips pulling back, baring my teeth in a snarl. I whirled and headed for the main body of tents.

Conan the Unconquered

Conan the Unconquered Conan the Triumphant

Conan the Triumphant The Eye of the World

The Eye of the World The Great Hunt

The Great Hunt Conan the Victorious

Conan the Victorious The Dragon Reborn

The Dragon Reborn The Fires of Heaven

The Fires of Heaven Winter's Heart

Winter's Heart Lord of Chaos

Lord of Chaos The Shadow Rising

The Shadow Rising Conan the Defender

Conan the Defender The Strike at Shayol Ghul

The Strike at Shayol Ghul The Path of Daggers

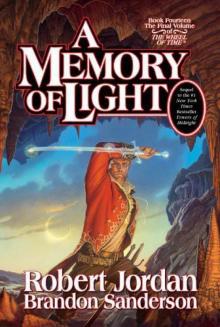

The Path of Daggers A Memory of Light

A Memory of Light Knife of Dreams

Knife of Dreams Crossroads of Twilight

Crossroads of Twilight Conan the Invincible

Conan the Invincible The Gathering Storm

The Gathering Storm Warrior of the Altaii

Warrior of the Altaii A Crown of Swords

A Crown of Swords The Wheel of Time

The Wheel of Time Towers of Midnight

Towers of Midnight Conan Chronicles 2

Conan Chronicles 2 Conan the Magnificent

Conan the Magnificent New Spring

New Spring What the Storm Means

What the Storm Means A Memory of Light twot-14

A Memory of Light twot-14 New Spring: The Novel

New Spring: The Novel Towers of midnight wot-13

Towers of midnight wot-13 A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14

A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14 A Crown of Swords twot-7

A Crown of Swords twot-7 Lord of Chaos twot-6

Lord of Chaos twot-6 The Great Hunt twot-2

The Great Hunt twot-2 The Shadow Rising twot-4

The Shadow Rising twot-4![Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/03/wheel_of_time-11_knife_of_dreams_preview.jpg) Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams

Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams The Dragon Reborn twot-3

The Dragon Reborn twot-3 The Wheel of Time Companion

The Wheel of Time Companion The Fires of Heaven twot-5

The Fires of Heaven twot-5 Prologue to Towers of Midnight

Prologue to Towers of Midnight The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8

The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8 The Path of Daggers twot-8

The Path of Daggers twot-8 By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light

By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light Crossroads of Twilight twot-10

Crossroads of Twilight twot-10 The Gathering Storm twot-12

The Gathering Storm twot-12 Winter's Heart twot-9

Winter's Heart twot-9 Knife of Dreams twot-11

Knife of Dreams twot-11 New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)

New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)