- Home

- Robert Jordan

Warrior of the Altaii Page 18

Warrior of the Altaii Read online

Page 18

“It’s my fault,” Selka said. “I was supposed to guard your right side, but they were so powerful I had to pay too much attention to merely keeping in the circle. Mayra, they nearly tossed me aside as if I was a child.”

“It’s all right, Selka. You did well. And as for this arm, if this tingling you say you have is left from an attack, I’ll definitely have to do something. And since they’re still after you, I’d better give you another protection against the Most High.”

Protections, or even arms, weren’t what was bothering me. “Mayra, did they discover the plan? Do they know how I intend to take Lanta?”

“He was serious,” Otogai exclaimed, and the others leaned closer to hear.

“I don’t think they did, Wulfgar. They could only have gotten it from you, and they didn’t have you long enough.”

“Then which was the true vision?” Bohemund asked. “We all saw them, but which one is true? Do we burn the Towers of Kaal or die in Low Town?”

Mayra shook her head. “Both were equally strong. Both have equal chance of happening.”

“Perhaps they didn’t get the plan,” Karlan suggested. “Perhaps they only got that we attack Lanta, and one vision shows Wulfgar’s plan succeeding, and the other shows their counterplan succeeding.”

“They’d never think of an attack on Lanta,” Dunstan said. “Certainly not by us, without a siege engine among us.”

“They still fear him,” Otogai added. “They tried to take him, and failing that, to kill him. That means they know he’s dangerous to their scheme without knowing how, because if they knew he was going to attack Lanta, they’d just put their guards on alert instead of going to all this trouble. I certainly don’t know of any plan that could get us in with the gates shut and guards standing to.”

“Unless they don’t know the specifics of the attack,” I said, “but do know that my hand must open the Iron Gates. Even if the plan might succeed with them waiting for it, it couldn’t succeed with me dead. That might be the way they see it.”

They looked at each other without speaking. Finally Dunstan nodded. “I say go ahead.”

“Go ahead,” Otogai said.

Karlan nodded. “Go ahead.”

The other two agreed, and Bohemund smiled grimly. “Then we ride on the morrow. May the baraca ride with us.”

“And I ride to Lanta with you,” said Mayra. “I claim the first part of your debt.”

“You ride with me,” I said. “And may the baraca ride with us.”

XXIII

A CLOUD OF DUST

The bustle of crowds through the Imperial Gate hadn’t been lessened by rumors of war or of the gathering tribes of the Plain. This was Lanta the Unconquerable. This was the city that turned back the invincible legions of Basrath. No war could touch her. No bandits of the Plain could affect her commerce. There was only a cloud of dust on the horizon.

A good part of the traffic was that needed for the everyday life of the city. Carts, and even caravans, of food rolled alongside the wide road. A steady stream of oil wagons came, and huge barrels in place of wagon boxes, to keep the lamps burning.

The guards gave little attention to any of it, certainly not to the oil wagon that was slowed to a stop in the gate by the press of the throng. It was certainly no different from any of the others. A tall, bearded fellow with a vacant stare walked beside the horse to guide it in the crowds. On the seat sat the merchant, his wife beside him, bundled from head to foot so not a glimmer of her showed. Occasionally he’d shout to the man by the horse, yelling for him to go this way or that to gain a bit on the rest, or to the man trailing the wagon, for him to be certain no one stole any of the oil.

One of the guards took notice of something and poked his companion amusedly. “Hey, oil seller,” he yelled. “You’re oiling the road.”

The merchant looked at the guard, suspicious of a joke, then stood up on the seat to look behind. The barrel blocked his view of the tap. Muttering to himself, he climbed down and walked back. His shriek of anguish was enough to send the guards into fits of laughter.

“Idiot! Imbecile! Will you drive me to penury?” A thin trickle of oil descended from the tap. The trail it left showed it’d been leaking for some time. “Close it! Close it! Do I have to tell you everything? If I’m forced to lose my profit on this, I’ll have every copper from your hide.”

Passersby close enough to see joined in the laughter as the servant tried vainly to close the tap. Despite the leak it appeared to be closed as far as it would go. Suddenly the tap twisted in his hands and came out of the barrel. The servant joined in with a wail as a gout of oil as thick as a man’s arm poured onto the road.

“Stop it up, witling! Stop up that hole!”

The merchant danced up and down in frustration while the servant tried to force the tap back in against the flow of oil. At last he managed to hammer it in place, but by that time at least half the oil in the wagon lay on the ground.

“Perfumed oil.” The merchant gestured helplessly at the puddles in the road as if he could say no more. “Perfumed oil.”

An officer of the City Guard who’d come out to see what was causing the commotion confronted him.

“I can tell that,” he said, waving a hand in front of his face. “Now get that wagon out of here before I make you haul sand to sop up this mess. Go on. You’re blocking the gate.”

“But what am I going to do about my oil?” the merchant wailed.

“You’re going to go. Now,” the officer said grimly.

Snatching off his cap, the merchant struck his servant with it. “Well? Didn’t you hear the gracious noble? Go. I don’t have all day. There’ll be others at market before me, and I must make every copper I can if I’m to avoid bankruptcy.”

The merchant continued his tirade as the wagon rolled forward, until he had to run to regain his seat. The crowd began to move ahead, and those behind grumbled on finding they had to pick their way through pools of oil in the road. The cloud of dust on the horizon grew larger.

The oil cart continued on toward the inner gate, but then turned off into a Low Town side street. Several others in the crowd who might have been expected to continue into the High City also turned off and stopped by the wagon.

I grinned as I let go of the horse lead and moved to the rear of the wagon. Mayra was climbing down from the seat.

“How can city women breathe in these traveling robes?” she complained as she loosened them. “They don’t let any air in.”

Bartu was stripping off his merchant’s garb, and Aelfric, the man who’d found Elspeth, no longer looked the oafish servant.

“We should find a shrine,” Bartu said, “and thank the city gods for the crowd. I was afraid we’d have to lose a wheel to get stopped, and I still don’t think they’d have let us go so easily if we had.”

“Don’t worry,” I told him. “It’s past, and we’re in.” I wasn’t as easy in my mind as I sounded. The dust cloud moved closer.

Finally a guard saw it. He stared in disbelief, then shouted, pointing. Other guards took up the cry, and the alarm bell over the gate began to ring. Deeper in the city more bells joined in, echoing and overlapping. It was a sound not heard in Lanta in the memory of most men.

I stripped off the stained tunic and worn sandals I wore and dug my own clothes and armor from a chest fastened to the wagon’s side. Bartu, Aelfric and the others did the same. If any of those pushing deeper into Low Town thought it strange to see men donning chain mail and belting on swords, they didn’t stop to question it.

As the bells rang, the great Iron Gates of Lanta slowly swung shut. Panic spread among the people still trying to get in as the way narrowed. Screaming and shouting, they forced their way through the gap, abandoning goods, horses, carts, anything that couldn’t advance in the press. The gates clanged shut, and the screams from outside died as the people there began to run along the walls, trying to escape whatever was coming. Did they but know it, they were the safest people

in Lanta.

Bartu handed me a crossbow. “It’s time, my lord?”

“It’s time.”

I put a long quarrel on the crossbow, one that stuck over the bow’s end and had a bundle of oily rags tied around the head. He struck flint and steel, and the rags flamed.

“With my own hand,” I said, and fired.

Even as the bolt was in the air I dropped the bow and was out and running, swords in hand, the others on my heels. The quarrel struck, the oil seemed to explode, and the whole width of the gate was engulfed in flames.

A guard ran out of one of the gate towers and skidded to a halt, staring at the fire. Then he caught sight of us, and his mouth dropped open. Perhaps he thought he’d somehow gotten on the wrong side of the gate, to find Altaii warriors. He tried to shout a warning, but the sound coming out was pushed back by my sword going in.

Shouldering open the door I burst into the lowest chamber of the tower. A startled guard appeared in front of me, then fell back, hands clasping a ruined throat. Another leaped to his feet to receive a boot in the crotch. As he doubled over, descending steel removed his pain and his head. Leaving those behind me to deal with the other guards I bounded up the stairs.

The sound of the alarm bells covered my coming. The first guard died without knowing what killed him. In the space of heartbeats Bartu, Aelfric and the rest were there, and I moved on. Higher we moved, and higher, faster and faster, and we dared leave no one behind but the dead. We raced against the sound of the bells that hid us like a cloak from the men on the wall outside the tower, men in numbers to brush us aside like kopwings. To buy that cloaking, to buy our lives, every man in that tower had to die before the bells stopped. The last man died, and as he died silence came. His fall sounded like thunder.

I froze, staring at the heavy door to the top level of the wall and waiting for the onslaught. A man moved, and I motioned for silence as if he’d shouted. Slowly my breathing returned to normal. The door remained shut.

Aelfric and Bartu hurried to place a balk of timber across the door. As it settled in the slots Bartu heaved a relieved sigh.

“We made it,” he said.

I shook my head. “Not yet. There’s a door like this on every level. Every one has to be barred, else we might as well invite the guards in. Quickly, now, and quietly.”

I raced ahead of them all the way to the bottom, leaving the doors to them. I’d said I knew the way my hand could open the Iron Gates of Lanta, but I still didn’t know for certain if I was right. It could still be that I’d led more men to useless deaths.

XXIV

BLOOD AND STEEL

In the road outside there was still some confusion, but the remaining people were fast disappearing, most of them into the High City. Inhabitants of Low Town had long since gone to ground. At the inner gate guards stood among the litter of abandoned peddlers’ barrows and pushcarts, looking toward the outer gate, staring at the raging fire. It seemed the baraca was indeed with us. They hadn’t seen us, and their gate stood open.

At the Iron Gate itself the great ball of flame was gone, but every crack and crevice in the road held flame, every depression supported a billow. And on the gate tendrils of smoke seeped from cracks between the iron plates.

The Iron Gates of Lanta. For how many centuries had that name gone unchallenged? Even Basrath hadn’t questioned it. To his death he’d boasted that only the solid metal of the Iron Gates had stopped him. I had questioned it. Sitting, looking at those gates, I’d begun to wonder how the plates were fastened together, and then how such a great mass of metal could be moved so easily. I’d gambled on a hunch, and so far I’d won. The gates weren’t solid iron, only iron plates on a wooden frame. And that wooden frame was burning.

Even as I watched a plate buckled, and a finger of flame appeared. Half the gamble was won. Now I’d only to wait for the fall of the pieces to see if I’d won it all. I was smiling as I ran back up to the third level. That was the lowest pierced with arrow slits. Through one of them the dust cloud was looming large, and the source of the cloud.

Riding on the wheels of twenty carts a huge tree, as thick as a man is tall, hurtled down the road toward the Iron Gate. On either side rode a hundred warriors, drawing on ropes, but in truth the behemoth had life and carried itself forward for its meeting with the flaming gate. Behind followed ten thousand Altaii lances, coming to tear the walls of Lanta down.

From below a sound impinged on my mind, a rhythmic pounding. “They’ve discovered the doors are barred,” I said.

We were moving down the stairs before the words were out of my mouth. I touched the bottom step on the second level just as the door crashed open, and a dozen guards spilled into the room trying to drop the timber they’d used for a ram and draw their swords all at the same time. The room was suddenly filled with flashing steel and shouting men, and more were coming.

I fought to get to the door. A Lantan sprang up before me, and I killed him without ever seeing his face. The door filled my eyes, the door and a hundred more guards pounding toward it. Another Lantan leaped for me. I took the wound he gave and knocked him aside. I had no more than a dozen heartbeats left anyway if that door wasn’t shut.

And then I was there, pushing it back, throwing my weight against it, but there was weight on the other side, now. A hand reached through the gap and poked blindly with a sword, blindly, but at me.

“The door,” I shouted.

The numbers were too much against me. It began to swing back in. Aelfric threw his weight beside mine, and another warrior added his. Behind us the fight still raged, but our fight was there. Bartu joined us, blood running down the side of his head. The door stopped. For an instant the scales teetered; then the last grain fell on our side. The gap narrowed.

Outside a man screamed, whether from frustration or because he was being crushed against the door by his fellows in their desperation I didn’t know. It was the sound of our victory in that small battle, though. His cry was cut off as the door slid shut. The only noises were panting and the futile pounding of fists against the door. Bartu brought another timber to bar the door, and we could turn to find out what had transpired behind us.

Every Lantan who’d entered the room lay dead. A victory, there, too, but not without its price. A young, red-haired warrior named Hotar lay on the floor trying to hold his life in his chest with his hands. I looked to Mayra, coming down the stairs, but she took one glance and shook her head. He was less than a year past his warrior brand, and he’d asked to come for the glory of being one of the first to enter Lanta. Instead I held him while he died. There’s little in the life of a warrior. Only blood and steel, that and no more.

“My lord.” Bartu tugged at my arm. “My lord. He’s dead, and there’s no time left. He’ll get his funeral fire, but we’ve got to go now.”

“We’ll go,” I said wearily.

We retreated to ground level, but there was no attempt to follow us, or to break down another door. They were too concerned about what was coming from the outside to worry about a handful of Altaii in one tower.

“It’s too bad you couldn’t have used a spell against them,” I said.

“Stick to your swords and your men’s law,” Mayra replied, “and leave the laws of magic to me.”

There was no more time for talking. Shouts came from the walls above, screams and the sound of panic. Then the tree, loosed by the warriors, struck the gates, a huge battering ram.

Those gates, inviolate for untold centuries, were sheared away as if by the hammer of a god. Like flung cards they spun into Low Town, leaving everything in their path broken and scattered. The ram, many wheels torn away by the impact, careened into Low Town. Its end struck a tavern, and it twisted in the road, rolling and spinning, tearing the fronts from inns and hostels. Halfway to the High City it came to rest, a wall across the road.

At the inner gate guards scurried like a kicked kes hive. The gates began to close, swinging slowly, hesitantly, for they were seldo

m moved. They moved a little way, then stopped, a mass of broken peddlers’ barrows and pushcarts jammed beneath them. Locally alarm bells rang again, but few in the city took up the call. The guards tried frantically, more like kes than ever, to clear the wreckage. They were too late.

Twenty Altaii lances leaped the burning oil and raced toward the inner gate, leaning low in their saddles as the horses cleared the giant log. Another twenty followed, and another, and another. Arrows from the walls emptied some saddles, but there was still confusion there, and disbelief about what was happening. And more lances came.

Then Orne was outside with horses. “It looks to be a restful enough spot, my lord, if resting is what’s on your mind, but I don’t think the wine’s very good here.”

“The wine isn’t bad,” I replied, “but the food’s bad, and I’ve never seen such ugly dancing girls.”

An arrow stuck in the door next to me, and I quickly swung into the saddle. I put spur to horse and headed for the High City, the others close behind and more Altaii lances close behind them. I hoped Mayra’s powers and charms could protect her. She’d refused steel armor, and I had no way to shelter her.

My horse took the jump over the tree in the road as if for sport. The inner gate was ours already, and some warriors had fought their way up the ramps that led to the road on top and the great weapons there. For the first time Altaii arrows flew from the Inner Wall, and the Lantans fell from the Outer. Altaii lances began to ride unhindered into the city.

I rode through without slowing, and the others with me. Behind followed a handpicked thousand, chosen for a special task. Other lances fanned out as they entered, spreading through the city. Still others rode up the ramps to the top of the Inner Wall.

There weren’t many guards on the Inner Wall, for the most part only the crews for the ballistae and catapults. None of those would hold long in the face of horsemen from the Plain. Soon the defenders of the Outer Wall would find their own firepots raining down on them, smashing into the open back of the wall and finding fuel in the wooden walls they’d added. Even then there were plumes of smoke rising behind us.

Conan the Unconquered

Conan the Unconquered Conan the Triumphant

Conan the Triumphant The Eye of the World

The Eye of the World The Great Hunt

The Great Hunt Conan the Victorious

Conan the Victorious The Dragon Reborn

The Dragon Reborn The Fires of Heaven

The Fires of Heaven Winter's Heart

Winter's Heart Lord of Chaos

Lord of Chaos The Shadow Rising

The Shadow Rising Conan the Defender

Conan the Defender The Strike at Shayol Ghul

The Strike at Shayol Ghul The Path of Daggers

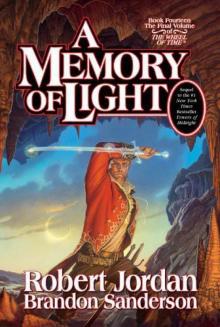

The Path of Daggers A Memory of Light

A Memory of Light Knife of Dreams

Knife of Dreams Crossroads of Twilight

Crossroads of Twilight Conan the Invincible

Conan the Invincible The Gathering Storm

The Gathering Storm Warrior of the Altaii

Warrior of the Altaii A Crown of Swords

A Crown of Swords The Wheel of Time

The Wheel of Time Towers of Midnight

Towers of Midnight Conan Chronicles 2

Conan Chronicles 2 Conan the Magnificent

Conan the Magnificent New Spring

New Spring What the Storm Means

What the Storm Means A Memory of Light twot-14

A Memory of Light twot-14 New Spring: The Novel

New Spring: The Novel Towers of midnight wot-13

Towers of midnight wot-13 A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14

A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14 A Crown of Swords twot-7

A Crown of Swords twot-7 Lord of Chaos twot-6

Lord of Chaos twot-6 The Great Hunt twot-2

The Great Hunt twot-2 The Shadow Rising twot-4

The Shadow Rising twot-4![Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/03/wheel_of_time-11_knife_of_dreams_preview.jpg) Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams

Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams The Dragon Reborn twot-3

The Dragon Reborn twot-3 The Wheel of Time Companion

The Wheel of Time Companion The Fires of Heaven twot-5

The Fires of Heaven twot-5 Prologue to Towers of Midnight

Prologue to Towers of Midnight The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8

The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8 The Path of Daggers twot-8

The Path of Daggers twot-8 By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light

By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light Crossroads of Twilight twot-10

Crossroads of Twilight twot-10 The Gathering Storm twot-12

The Gathering Storm twot-12 Winter's Heart twot-9

Winter's Heart twot-9 Knife of Dreams twot-11

Knife of Dreams twot-11 New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)

New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)