- Home

- Robert Jordan

The Great Hunt Page 20

The Great Hunt Read online

Page 20

“Changu was on guard in the dungeon yesterday,” Rand said slowly.

“And Nidao. They had the second watch. They always stayed together, even if they had to trade or do extra duty for it. They were not on guard when it happened, but. . . . They fought at Tarwin’s Gap, a month gone, and saved Lord Agelmar when his horse went down with Trollocs all around him. Now this. Darkfriends.” He drew a deep breath. “Everything is breaking apart.”

A man on horseback forced his way through the throng lining the street and joined in behind Ingtar. He was a townsman, by his clothes, lean, with a lined face and graying hair cut long. A bundle and waterbottles were lashed behind his saddle, and a short-bladed sword and a notched sword-breaker hung at his belt, along with a cudgel.

Ingtar noticed Rand’s glances. “This is Hurin, our sniffer. There was no need to let the Aes Sedai know about him. Not that what he does is wrong, you understand. The King keeps a sniffer in Fal Moran, and there’s another in Ankor Dail. It’s just that Aes Sedai seldom like what they do not understand, and with him being a man. . . . It’s nothing to do with the Power, of course. Aaaah! You tell him, Hurin.”

“Yes, Lord Ingtar,” the man said. He bowed low to Rand from his saddle. “Honor to serve, my Lord.”

“Call me Rand.” Rand stuck out his hand, and after a moment Hurin grinned and took it.

“As you wish, my Lord Rand. Lord Ingtar and Lord Kajin don’t mind a man’s ways—and Lord Agelmar, of course—but they say in the town you’re an outland prince from the south, and some outland lords are strict for every man in his place.”

“I’m not a lord.” At least I’ll get away from that, now. “Just Rand.”

Hurin blinked. “As you wish, my Lor—ah—Rand. I’m a sniffer, you see. Been one four years this Sunday. I never heard of such a thing before then, but I hear there’s a few others like me. It started slow, catching bad smells where nobody else smelled anything, and it grew. Took a whole year before I realized what it was. I could smell violence, the killing and the hurting. Smell where it happened. Smell the trail of those who did it. Every trail’s different, so there’s no chance of mixing them up. Lord Ingtar heard of it, and took me in his service, to serve the King’s justice.”

“You can smell violence?” Rand said. He could not help looking at the man’s nose. It was an ordinary nose, not large, not small. “You mean you can really follow somebody who, say, killed another man? By smell?”

“I can that, my Lor—ah—Rand. It fades with time, but the worse the violence, the longer it lasts. Aiie, I can smell a battlefield ten years old, though the trails of the men who were there are gone. Up near the Blight, the trails of the Trollocs almost never fade. Not much to a Trolloc but killing and hurting. A fight in a tavern, though, with maybe a broken arm . . . that smell’s gone in hours.”

“I can see where you wouldn’t want Aes Sedai to find out.”

“Ah, Lord Ingtar was right about the Aes Sedai, the Light illumine them—ah—Rand. There was one in Cairhien once—Brown Ajah, but I swear I thought she was Red before she let me go—she kept me a month trying to find out how I do it. She didn’t like not knowing. She kept muttering, ‘Is it old come again, or new?’ and staring at me until you would have thought I was using the One Power. Almost had me doubting myself. But I haven’t gone mad, and I don’t do anything. I just smell it.”

Rand could not help remembering Moiraine. Old barriers weaken. There is something of dissolution and change about our time. Old things walk again, and new things are born. We may live to see the end of an Age. He shivered. “So we’ll track those who took the Horn with your nose.”

Ingtar nodded. Hurin grinned proudly, and said, “We will that—ah—Rand. I followed a murderer to Cairhien, once, and another all the way to Maradon, to bring them back for the King’s justice.” His grin faded, and he looked troubled. “This is the worst ever, though. Murder smells bad, and the trail of a murderer stinks with it, but this. . . .” His nose wrinkled. “There were men in it last night. Darkfriends, must be, but you can’t tell a Darkfriend by smell. What I’ll follow is the Trollocs, and the Halfmen. And something even worse.” He trailed off, frowning and muttering to himself, but Rand could hear it. “Something even worse, the Light help me.”

They reached the city gates, and just beyond the walls Hurin lifted his face to the breeze. His nostrils flared, then he gave a snort of disgust. “That way, my Lord Ingtar.” He pointed south.

Ingtar looked surprised. “Not toward the Blight?”

“No, Lord Ingtar. Faugh!” Hurin wiped his mouth on his sleeve. “I can almost taste them. South, they went.”

“She was right, then, the Amyrlin Seat,” Ingtar said slowly. “A great and wise woman, who deserves better than me to serve her. Take the trail, Hurin.”

Rand turned and peered back through the gates, up the street to the keep. He hoped Egwene was all right. Nynaeve will look after her. Maybe it’s better this way, like a clean cut, too quick to hurt till after it’s done.

He rode after Ingtar and the Gray Owl banner, south. The wind was making up, and cold against his back despite the sun. He thought he heard laughter in it, faint and mocking.

The waxing moon lit the humid, night-dark streets of Illian, which still rang with celebration left over from daylight. In only a few more days, the Great Hunt of the Horn would be sent forth with pomp and ceremony that tradition claimed dated to the Age of Legends. The festivities for the Hunters had blended into the Feast of Teven, with its famed contests and prizes for gleemen. The greatest prize of all, as always, would go for the best telling of The Great Hunt of the Horn.

Tonight the gleemen entertained in the palaces and mansions of the city, where the great and mighty disported themselves, and the Hunters come from every nation to ride out and find, if not the Horn of Valere itself, at least immortality in song and story. They would have music and dancing, and fans and ices to dispel the year’s first real heat, but carnival filled the streets, too, in the moon-bright muggy night. Every day was a carnival, until the Hunt departed, and every night.

People ran past Bayle Domon in masks and costumes bizarre and fanciful, many showing too much flesh. Shouting and singing they ran, a half dozen together, then scattered pairs giggling and clutching each other, then twenty in a raucous knot. Fireworks crackled in the sky, gold and silver bursts against the black. There were almost as many Illuminators in the city as there were gleemen.

Domon spared little thought for fireworks, or for the Hunt. He was on his way to meet men he thought might be trying to kill him.

He crossed the Bridge of Flowers, over one of the city’s many canals, into the Perfumed Quarter, the port district of Illian. The canal smelled of too many chamber pots, with never a sign that there had ever been flowers near the bridge. The quarter smelled of hemp and pitch from the shipyards and docks, and sour harbor mud, all of it made fiercer by heated air that seemed nearly damp enough to drink. Domon breathed heavily; every time he returned from the northcountry he found himself surprised, for all he had been born there, at the early summer heat in Illian.

In one hand he carried a stout cudgel, and the other hand rested on the hilt of the short sword he had often used in defending the decks of his river trader from brigands. No few footpads stalked these nights of revelry, where the pickings were rich and most were deep in wine.

Yet he was a broad, muscular man, and none of those out for a catch of gold thought him rich enough, in his plain-cut coat, to risk his size and his cudgel. The few who caught a clear glimpse of him, when he passed through light spilling from a window, edged back till he was well past. Dark hair that hung to his shoulders and a long beard that left his upper lip bare framed a round face, but that face had never been soft, and now it was set as grimly as if he meant to batter his way through a wall. He had men to meet, and he was not happy about it.

More revelers ran past singing off-key, wine mangling their words. “The Horn of Valere,” my aged grandmother! Do

mon thought glumly. It be my ship I do want to hang on to. And my life, Fortune prick me.

He pushed into an inn, under a sign of a big, white-striped badger dancing on its hind legs with a man carrying a silver shovel. Easing the Badger, it was called, though not even Nieda Sidoro, the innkeeper, knew what the name meant; there had always been an inn of the name in Illian.

The common room, with sawdust on the floor and a musician softly strumming a twelve-stringed bittern in one of the Sea Folk’s sad songs, was well lighted and quiet. Nieda allowed no commotion in her place, and her nephew, Bili, was big enough to carry a man out with either hand. Sailors, dockworkers, and warehousemen came to the Badger for a drink and maybe a little talk, for a game of stones or darts. The room was half full now; even men who liked quiet had been lured out by carnival. The talk was soft, but Domon caught mentions of the Hunt, and of the false Dragon the Murandians had taken, and of the one the Tairens were chasing through Haddon Mirk. There seemed to be some question whether it would be preferable to see the false Dragon die, or the Tairens.

Domon grimaced. False Dragons! Fortune prick me, there be no place safe these days. But he had no real care for false Dragons, any more than for the Hunt.

The stout proprietress, with her hair rolled at the back of her head, was wiping a mug, keeping a sharp eye on her establishment. She did not stop what she was doing, or even look at him, really, but her left eyelid drooped, and her eyes slanted toward three men at a table in the corner. They were quiet even for the Badger, almost somber, and their bell-shaped velvet caps and dark coats, embroidered across the chest in bars of silver and scarlet and gold, stood out among the plain dress of the other patrons.

Domon sighed and took a table in a corner by himself. Cairhienin, this time. He took a mug of brown ale from a serving girl and drew a long swallow. When he lowered the mug, the three men in striped coats were standing beside his table. He made an unobtrusive gesture, to let Nieda know that he did not need Bili.

“Captain Domon?” They were all three nondescript, but there was an air about the speaker that made Domon take him for their leader. They did not appear to be armed; despite their fine clothes, they looked as if they did not need to be. There were hard eyes in those so very ordinary faces. “Captain Bayle Domon, of the Spray?”

Domon gave a short nod, and the three sat down without waiting for an invitation. The same man did the talking; the other two just watched, hardly blinking. Guards, Domon thought, for all their fine clothes. Who do he be to have a pair of guards to look over him?

“Captain Domon, we have a personage who must be brought from Mayene to Illian.”

“Spray be a river craft,” Domon cut him off. “Her draft be shallow, and she has no the keel for deep water.” It was not exactly true, but close enough for landsmen. At least it be a change from Tear. They be getting smarter.

The man seemed unperturbed at the interruption. “We had heard you were giving up the river trade.”

“Maybe I do, and maybe no. I have no decided.” He had, though. He would not go back upriver, back to the Borderlands, for all the silk shipped in Tairen bottoms. Saldaean furs and ice peppers were not worth it, and it had nothing to do with the false Dragon he had heard of there. But he wondered again how anyone knew. He had not spoken of it to anyone, yet the others had known, too.

“You can coast to Mayene easily enough. Surely, Captain, you would be willing to sail along the shoreline for a thousand gold marks.”

Despite himself, Domon goggled. It was four times the last offer, and that had been enough to make a man’s jaw drop. “Who do you want me to fetch for that? The First of Mayene herself? Has Tear finally forced her all the way out, then?”

“You need no names, Captain.” The man set a large leather pouch on the table, and a sealed parchment. The pouch clinked heavily as he pushed them across the table. The big red wax circle holding the folded parchment shut bore the many-rayed Rising Sun of Cairhien. “Two hundred on account. For a thousand marks, I think you need no names. Give that, seal unbroken, to the Port Captain of Mayene, and he will give you three hundred more, and your passenger. I will hand over the remainder when your passenger is delivered here. So long as you have made no effort to discover that personage’s identity.”

Domon drew a deep breath. Fortune, it be worth the voyage if there be never another penny beyond what be in that sack. And a thousand was more money than he would clear in three years. He suspected that if he probed a little more, there would be other hints, just hints, that the voyage involved hidden dealings between Illian’s Council of Nine and the First of Mayene. The First’s city-state was a province of Tear in all but name, and she would no doubt like Illian’s aid. And there were many in Illian who said it was time for another war, that Tear was taking more than a fair share of the trade on the Sea of Storms. A likely net to snare him, if he had not seen three like it in the past month.

He reached to take the pouch, and the man who had done all the talking caught his wrist. Domon glared at him, but he looked back undisturbed.

“You must sail as soon as possible, Captain.”

“At first light,” Domon growled, and the man nodded and released his hold.

“At first light, then, Captain Domon. Remember, discretion keeps a man alive to spend his money.”

Domon watched the three of them leave, then stared sourly at the pouch and the parchment on the table in front of him. Someone wanted him to go east. Tear or Mayene, it did not matter so long as he went east. He thought he knew who wanted it. And then again, I have no a clue to them. Who could know who was a Darkfriend? But he knew that Darkfriends had been after him since before he left Marabon to come back downriver. Darkfriends and Trollocs. Of that, he was sure. The real question, the one he had not even a glimmer of an answer for, was why?

“Trouble, Bayle?” Nieda asked. “You do look as if you had seen a Trolloc.” She giggled, an improbable sound from a woman her size. Like most people who had never been to the Borderlands, Nieda did not believe in Trollocs. He had tried telling her the truth of it; she enjoyed his stories, and thought they were all lies. She did not believe in snow, either.

“No trouble, Nieda.” He untied the pouch, dug a coin out without looking, and tossed it to her. “Drinks for everyone till that do run out, then I’ll give you another.”

Nieda looked at the coin in surprise. “A Tar Valon mark! Do you be trading with the witches now, Bayle?”

“No,” he said hoarsely. “That I do not!”

She bit the coin, then quickly snugged it away behind her broad belt. “Well, it be gold for that. And I suspect the witches be no so bad as some make them out, anyway. I’d no say so much to many men. I know a money changer who do handle such. You’ll no have to give me another, with as few as be here tonight. More ale for you, Bayle?”

He nodded numbly, though his mug was still almost full, and she trundled off. She was a friend, and would not speak of what she had seen. He sat staring at the leather pouch. Another mug was brought before he could make himself open it enough to look at the coins inside. He stirred them with a callused finger. Gold marks glittered up at him in the lamplight, every one of them bearing the damning Flame of Tar Valon. Hurriedly he tied the bag. Dangerous coins. One or two might pass, but so many would say to most people exactly what Nieda thought. There were Children of the Light in the city, and although there was no law in Illian against dealing with Aes Sedai, he would never make it to a magistrate if the Whitecloaks heard of this. These men had made sure he would not simply take the gold and stay in Illian.

While he was sitting there worrying, Yarin Maeldan, his brooding, stork-like second on Spray, came into the Badger with his brows pulled down to his long nose and stood over the captain’s table. “Carn’s dead, Captain.”

Domon stared at him, frowning. Three others of his men had already been killed, one each time he refused a commission that would take him east. The magistrates had done nothing; the streets were dangerous at nigh

t, they said, and sailors a rough and quarrelsome lot. Magistrates seldom troubled themselves with what happened in the Perfumed Quarter, as long as no respectable citizens were injured.

“But this time I did accept them,” he muttered.

“ ’Tisn’t all, Captain,” Yarin said. “They worked Carn with knives, like they wanted him to tell them something. And some more men tried to sneak aboard Spray not an hour gone. The dock watch ran them off. Third time in ten days, and I never knew wharf rats to be so persistent. They like to let an alarm die down before they try again. And somebody tossed my room at the Silver Dolphin last night. Took some silver, so I’d think it was thieves, but they left that belt buckle of mine, the one set with garnets and moonstones, lying right out in plain sight. What’s going on, Captain? The men are afraid, and I’m a little nervous myself.”

Domon reared to his feet. “Roust the crew, Yarin. Find them and tell them Spray sails as soon as there do be men enough aboard to handle her.” Stuffing the parchment into his coat pocket, he snatched up the bag of gold and pushed his second out the door ahead of him. “Roust them, Yarin, for I’ll leave any man who no makes it, standing on the quay as he is.”

Domon gave Yarin a shove to start him running, then stalked off toward the docks. Even footpads who heard the clinking of the pouch he carried steered clear of him, for he walked now like a man going to do murder.

There were already crewmen scrambling aboard Spray when he arrived, and more running barefoot down the stone quay. They did not know what he feared was pursuing him, or even that anything did pursue him, but they knew he made good profits, and after the Illianer way, he gave shares to the crew.

Spray was eighty feet long, with two masts, and broad in the beam, with room for deck cargo as well as in the holds. Despite what Domon had told the Cairhienin—if they had been Cairhienin—he thought she could stand the open water. The Sea of Storms was quieter in the summer.

“She’ll have to,” he muttered, and strode below to his cabin.

Conan the Unconquered

Conan the Unconquered Conan the Triumphant

Conan the Triumphant The Eye of the World

The Eye of the World The Great Hunt

The Great Hunt Conan the Victorious

Conan the Victorious The Dragon Reborn

The Dragon Reborn The Fires of Heaven

The Fires of Heaven Winter's Heart

Winter's Heart Lord of Chaos

Lord of Chaos The Shadow Rising

The Shadow Rising Conan the Defender

Conan the Defender The Strike at Shayol Ghul

The Strike at Shayol Ghul The Path of Daggers

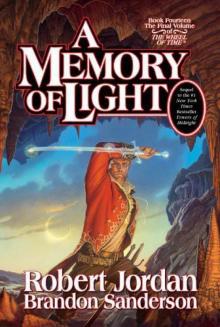

The Path of Daggers A Memory of Light

A Memory of Light Knife of Dreams

Knife of Dreams Crossroads of Twilight

Crossroads of Twilight Conan the Invincible

Conan the Invincible The Gathering Storm

The Gathering Storm Warrior of the Altaii

Warrior of the Altaii A Crown of Swords

A Crown of Swords The Wheel of Time

The Wheel of Time Towers of Midnight

Towers of Midnight Conan Chronicles 2

Conan Chronicles 2 Conan the Magnificent

Conan the Magnificent New Spring

New Spring What the Storm Means

What the Storm Means A Memory of Light twot-14

A Memory of Light twot-14 New Spring: The Novel

New Spring: The Novel Towers of midnight wot-13

Towers of midnight wot-13 A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14

A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14 A Crown of Swords twot-7

A Crown of Swords twot-7 Lord of Chaos twot-6

Lord of Chaos twot-6 The Great Hunt twot-2

The Great Hunt twot-2 The Shadow Rising twot-4

The Shadow Rising twot-4![Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/03/wheel_of_time-11_knife_of_dreams_preview.jpg) Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams

Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams The Dragon Reborn twot-3

The Dragon Reborn twot-3 The Wheel of Time Companion

The Wheel of Time Companion The Fires of Heaven twot-5

The Fires of Heaven twot-5 Prologue to Towers of Midnight

Prologue to Towers of Midnight The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8

The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8 The Path of Daggers twot-8

The Path of Daggers twot-8 By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light

By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light Crossroads of Twilight twot-10

Crossroads of Twilight twot-10 The Gathering Storm twot-12

The Gathering Storm twot-12 Winter's Heart twot-9

Winter's Heart twot-9 Knife of Dreams twot-11

Knife of Dreams twot-11 New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)

New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)