- Home

- Robert Jordan

Conan Chronicles 2 Page 24

Conan Chronicles 2 Read online

Page 24

“They would tear you to pieces at my command,” the veiled woman told him. “Now speak. Tell me all.”

Galbro began to babble. Words spilled from his mouth like water from a fountain. The bronze figure, described in minute detail. How he learned of it, and the attempts to secure it. Yet even in his terror he held back the true description of the giant northlander. Some tiny portion of him wanted to be part of killing this man who had endangered him; a larger part wanted whatever the veiled woman might pay for the piece. Did she know how to obtain it without him she might decide his usefulness was at an end. He knew she had others like him who served her, and Baraca reminded him of the deadliness of her wrath. When his torrent of speech ended, he lay waiting in dread.

“I dislike those who keep things from me,” she said at last, and he shivered at the thought of her dislike. “Secure this bronze, Galbro. Obey me implicitly, and I will forgive your lies. Fail …”

She did not have to voice the threat. His whirling mind provided a score of them, each worse than the last. “I will obey, my lady,” he sobbed, scrubbing his face in the dust of the floor. “I will obey. I will obey.”

Not until her footsteps had faded from the room could he bring himself to stop the litany. Raising his head he stared wildly about the room, filled with joyous relief that he was alone and still alive. The eagles caught his eye, and he moaned. They were still again, but one leaned forward with wings half raised as if ready to swoop at him from its perch. The other still clung to the table, head swiveled to pierce him with its amber gaze.

He wanted to flee, yet he knew with a sinking feeling that he could not run far enough or fast enough to escape her. That accursed northlander was responsible for this. If not for him everything could have gone on as before. Rage built in him, comforting rage that overlaid his terror. He would make the northlander pay for everything that had happened to him. That big man would pay.

Synelle waited until she was in her palanquin—unadorned for anonymity—with the pale gray curtains safely drawn before lowering her veil. The bearers carried her from the courtyard of the small house where she had met Galbro without a word needed from her. Tongueless, so they could not speak of where they had borne her, they knew the need to serve her perfectly as well as did the sly-faced thief.

It was well she always went to these meetings prepared. A cloth on which Galbro had wiped his sweat, obtained by another of her minions, a few feathers plucked from the eagles, these had given her the means to quell the thief. She could rest at her ease knowing the man’s soul was seared with the need for absolute obedience. And yet for once the gentle swaying of the platform did not lull her as she lolled on silken cushions.

Something about the sly little man’s description of the bronze produced an irritating tickle in the back of her mind. She had encountered many representations of Al’Kiir’s head, many medallions and amulets embossed with his head or the symbol of the horns, but never before a complete figure. It sounded so detailed, perhaps an exact duplicate of the actual body of the god. Her face went blank with astonishment. In one of the manuscript fragments she had gathered there was … something. She was sure of it.

She parted the forward curtains a slit. “Faster!” she commanded. “Erlik blast your souls, faster!”

The bearers increased their pace to a run, forcing their way through the crowds, careless of the curses that followed them. Synelle would do more than curse if they failed to obey. Within, she pounded a small fist against her thigh in frustration at the time it took to cross the city.

As soon as the palanquin entered the courtyard of her mansion, before the bearers could lower it to the slate tiles, Synelle leaped out. Even in her haste hate flickered through her at the sight of the house. As large as any palace in the city, it still was not a palace. The white-stuccoed walls and red-tiled roof were suitable for the dwelling of a merchant. Or a woman. By ancient law no woman, not even a princess, could maintain a palace within the walls of Ianthe. But she would change that. By the gods, if what she thought were true she would change it within the month. Why wait for Valdric to die? Not even the army could stand against her. Iskandrian, the White Eagle of Ophir, would kneel at her feet along with the great lords of Ophir.

Dropping her cloak for a serving maid to tend to, she raised her robes to her hips and ran, heedless of servants who stared at bare, flashing limbs. To the top floor of the mansion she ran, to a windowless room where only one other but herself was allowed, and that one with her mind ensorceled to forget what lay within, to die did anyone attempt to force the awful knowledge from her.

Golden sconces on the walls held pale, perfumed candles, yet all their light could not thrust back an air of darkness, the feel of a shrine to evil Shrine it was, in a way, though there was no idol, no place for votive offerings. Three long tables, polished till they gleamed, were all the furnishings the room contained. On one were flasks of liquids that bubbled in their sealed containers or glowed with eery lights, vials of powders noxious and obscene, the tools of her painfully learned craft. The second was covered with amulets and talismans; some held awesome powers she could detect but not yet wield. Al’Kiir would give them to her.

It was to the third table she hurried, for there were the fragments of scroll, the tattered pages of parchment and vellum that she had slowly and carefully gathered over the years. There was the dark knowledge of sorceries the world had attempted to forget, sorceries that would give her power. Hastily she pawed through them, for once careless of flakes that dropped from ancient pages. She found what she sought, and easily read in a language dead a thousand years. She was perhaps the last person in the world capable of reading that extinct tongue, for the scholar who had taught her she had had strangled with his own beard, his wife and children smothered in their beds to be doubly sure. Death guarded secrets far better than gold.

An eager gleam lit her dark eyes, and she read again the passage she had found.

Lo, call to the great god, entreating him, and set before the image, the succedaneum, the bridge between worlds, as a beacon to glorify the way of the god to thee.

She had thought this spoke of the priestess as bridge and beacon, placing herself before the image of Al’Kiir, but that which lay beneath the mountain was not an image. It was material body of the god. It must be the image that was to be placed before the priestess during the rites. The image. The bronze figure. It had to be. A thrill of triumph coursed through her as she swept from the room.

In the corridor a serving girl busily lighting silver lamps hung from the walls awkwardly made obeisence clutching her coal-pot and tongs.

Synelle had not realized how close the fall of darkness came. Twilight was almost on the city; precious time wasted away as she stood there. “Find Lord Taramenon,” she commanded, “and bid him come to my dressing chamber immediately. Run, girl!” The serving girl ran, for the Lady Synelle’s displeasures brought punishments best not thought of.

There was no need to ask if the handsome young lord was in her mansion. Taramenon wished to be king, a foolish desire for one with neither the proper blood lines nor money, and one he believed he had hidden from her. It was true he was the finest sword in Ophir—she had made a point of binding the best bladesmen of the land to her service—but that counted little in the quest for a throne. He followed Synelle in her own seeking because he believed in his arrogance that she would find it impossible to rule without a husband by her side, because he thought in his pride that he would be that husband. Thus he would gain his crown. She had done nothing to dissuade him from the belief. Not yet.

Four tirewomen, lithe matched blondes in robes that seemed to be but vapors of silk, paused only to bend knee before hurrying forward, moving as gracefully as dancers, as Synelle entered her dressing chamber. Her agents had gone to great efforts to find the four, sisters of noble Corinthian blood with but a year separating each from the next, Synelle herself had seen to the breaking and training of them. They followed her submissively a

nd silently as she strolled about the room, removing her garments without once impeding her progress in any way. In nakedness more resplendant than any satins or silks, long-limbed, full-breasted and sleek, Synelle allowed them to minister to her. One held an ivory-framed mirror while another used delicate fur brushes to freshen the kohl on Synelle’s eyelids and the rouge on her lips. The others wiped her softly with cool, damp clothes, and annointed her with rare perfume of Vendhya, priced at one gold coin the drop.

The heavy tread of a man’s boots sounded in the antechamber, and the tirewomen scurried to fetch a lounging robe of scarlet velvet. Synelle refused to hold out her arms for them to slip it on until the steps were at the very door.

Taramenon gasped at the tantalizing flash of silken curves, quickly sheathed, that greeted his entrance. He was tall, broad of shoulders and deep of chest, with an aquiline nose and deep brown eyes that had melted the hearts of many women. Synelle was glad that he did not follow the fashion in beards, being rather clean shaven. She was also pleased to note the quickening of his breath as he gazed at her.

“Leave me,” she commanded, belting tight the red satin sash of her robe. The girls filed obediently from the room.

“Synelle,” Taramenon said thickly as soon as they were gone, and stepped forward as if to take her in his arms.

She stopped him with an upraised hand. There was no time for such frivolity, no matter how amusing it might usually be to make him writhe with a desire she had no intention of slaking. Her studies told her there were powers to be gained from allowing a man to take her, and dedicating that taking to Al’Kiir, but she knew Taramenon’s plans for her. And she had seen too many proud, independent women give themselves to a man only to discover they had given pride and independence as well Not for her listening breathlessly for a lover’s footstep, smiling at his laughter, weeping at his frowns, running to tend to his wants like the meanest slave. She would not risk such an outcome. She would never give herself to any man.

“Send your two best swordsmen after yourself to find and follow Galbro,” she said, “without allowing him to become aware of it. He seeks a bronze, an image of Al’Kiir the length of a big man’s forearm, but it is too important to trust to him. When he has located it for them, they are to secure it and bring it to me at once. Do you understand, Taramenon? Are you listening?”

“I listen,” he said hoarsely, a touch of anger in his voice. “When you summoned me to your dressing chamber, at this hour, I thought something other than an accursed figure was on your mind.”

A seductive smile caressed her full lips, and she moved closer to him, until her breasts were pressed against him. “There will be time for that when the throne is secure,” she said softly. Her slender fingers brushed his mouth. “All the time in the world.” His arms began to come up around her, but she stepped smoothly out of his embrace. “First the throne, Taramenon, and this bronze you call accursed is vital to attaining that. Send the men tonight. Now.”

She watched a multitude of emotions cross his face, and wondered yet again at how transparent were the minds of men. No doubt he thought his features unreadable, yet she knew he was adding this incident to a host of others, cataloguing the ways he would make her pay for them once she was his.

“It will be done, Synelle,” he growled at last.

When he was gone her smile turned to one of ambition triumphant. Power would be hers. The smile became full-throated laughter. It would be hers, and hers alone.

V

The night streets of Ianthe were dark and empty, yet near the palace of Baron Timeon a shadow moved. A cloaked and hooded figure pressed itself to the thickly-ornamented marble walls, and cool green eyes, slightly tilted above high cheekbones, surveyed the guards marching their rounds among the thick, fluted columns of alabaster. All very well, those guards, but would he who lay sleeping within remember his own thief’s tricks?

The cloak was discarded, revealing a woman in tight-fitting tunic and snug breeches of buttery leather, with soft red boots on her feet. Moonlight shimmered on titian hair tied back from her face with a cord. Quickly she undid her sword belt and refastened it with her Turanian scimitar hanging down her back, then checked the leather sack hanging at her side. Strong, slender fingers tested the niveous marble carvings of the wall, and then she was climbing like a monkey.

Below the edge of the flat roof she paused. Boots grated on slate tiles. He remembered. Yet for all the reputation this Free-Company was building in the country, they were yet soldiers. Those on the roof walked regular paths, as sentries in a camp. The measured tread came closer, closer. And then it was receding.

As agile as a panther, she was onto the roof, running on silent feet, losing herself in the shadows of two score chimneys. At the drop of the central garden around which the entire palace was arranged, she fell to her belly and peered down. There were the windows of his sleeping chamber. They were dark. So he did sleep. She would have expected him to be carousing with yet another in a long line of all too willing wenches. It was one of the things she remembered most about him, his eye for women and theirs for him.

Knowledge had been easily come by. Not even bribes had been necessary. All that had been required was for her to pretend to be a serving woman—though that had been no small a task in itself, given her lush beauty; serving maids with curves like hers soon found themselves promoted to the master’s bed—and chat to the women of Baron Timeon’s palace in the markets. They had been eager to tell about the great house in which they served, about their fat master and his constantly changing parade of women, about the hard-eyed warriors who had hired themselves to him. Especially about the warriors they had been willing to talk, giggling and teasing each other about returning from the stable with hay covering the back of a robe and stolen moments in secluded corners of the garden.

She would have wagered there were guards in that garden as well as on the roof, but those did not worry her. From the leather sack she produced a rope woven of black-dyed silk, to the end of which was fastened a padded grapnel. The metal prongs hooked on the scrollwork along the roof-edge; the rope fell invisibly into the darkness below. It was just long enough to reach the window she sought.

A short climb downward, and she was inside the room. It was as black as Zandru’s Seventh Hell. A dagger found its way into her hand … and she stopped dead. What if there were some error in her information? She did not want to kill the wrong man. She had to be sure.

Mentally cursing her own foolishness, she felt in the darkness for a table, for a lamp … and yes, a coal-box and tongs. She puffed softly on the coal till it glowed, held it to the wick. Light bloomed, and she gasped at the apparition on the table beside the brass lamp. Horned malevolence glared at her. It was but a bronze figure, yet she sensed evil in the thing, and primeval instinct deep within her told her that evil was directed at women. Could the man she sought have changed so much as to keep such monstrosity in his chamber? The man she sought!

Heart pounding, she spun, dagger raised. He still slept, a young giant sprawled in his slumber, Conan of Cimmeria. Soft-footed she crept closer to his bed, her eyes drinking him in, the planes of his face, the breadth of his shoulders, the massive arms that had …

Stop, she commanded herself. How many wrongs had this man committed against her? She had lived on the plains of Zamora and Turan with the freedom of the hawk till Conan had come, and brought with him the destruction of her band of brigands. For his stupid male honor and the matter of a silly oath she had made him swear in a moment of anger, he had allowed her to be sold into slavery, into a zenana in Sultanapur. Every time the switch had kissed her buttocks, every time she had been forced to dance naked for the pleasure of the fat merchant who had been her master and his friends, all these could be laid at Conan’s feet.

When at last she had escaped and fled to Nemedia, become the queen of the smugglers of that country, he had appeared again. And before he was done she must needs pack her hard-acquired wealth on sumpter animal

s and flee again.

She had escaped him, then, but she could not escape his memory, the memory of his building fires in her, fires that she came to crave like the smoker of the yellow lotus craved his pipe. That memory had hounded her, driven her into riotous living and excesses that shocked even the jaded court of Aquilonia. Only when all her gold was gone had she known freedom again. Once more she had taken up the life she loved, living by her wits and her sword. She had sought a new country, Ophir, and raised a new band of rogues.

How many months gone had the first rumors come to her of a huge northerner whose Free-Company was a terror to all who opposed him? How long had she tried to convince herself that it was not the same man who always brought ruin to her? Once more she found herself within the same borders as he, but this time she would not flee. She would be free of him at last. With a sob she raised the dagger high and brought it down.

A strange sound penetrated Conan’s dreams—a woman’s sob, he thought drowsily—and brought him awake. He had just time to see a shape beside his bed, see the descending dagger, and then he was rolling aside.

The dagger slashed into the mattress where his chest had been, and the force of the missed stab brought his attacker down on top of him. Instantly he seized the shape—the back of his brain noted a curious softness—and hurled it across the room. In the same motion he leaped from the bed, seized the worn leather-wrapped hilt of his broadsword and slung the scabbard aside. It was then that he saw his assailant clearly for the first time.

“Karela!” he exclaimed.

The auburn-haired beauty rising warily from the floor near the wall snarled at him. “Yes, Derketo blast your eyes! And would she had made you sleep just one moment more.”

His gaze went to the dagger thrust into his mattress, and his eyebrows raised. But all he said was, “I thought you went to Aquilonia to live the life of a lady.”

Conan the Unconquered

Conan the Unconquered Conan the Triumphant

Conan the Triumphant The Eye of the World

The Eye of the World The Great Hunt

The Great Hunt Conan the Victorious

Conan the Victorious The Dragon Reborn

The Dragon Reborn The Fires of Heaven

The Fires of Heaven Winter's Heart

Winter's Heart Lord of Chaos

Lord of Chaos The Shadow Rising

The Shadow Rising Conan the Defender

Conan the Defender The Strike at Shayol Ghul

The Strike at Shayol Ghul The Path of Daggers

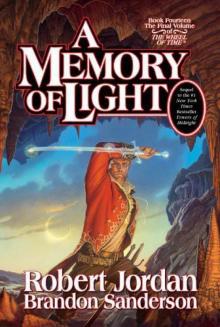

The Path of Daggers A Memory of Light

A Memory of Light Knife of Dreams

Knife of Dreams Crossroads of Twilight

Crossroads of Twilight Conan the Invincible

Conan the Invincible The Gathering Storm

The Gathering Storm Warrior of the Altaii

Warrior of the Altaii A Crown of Swords

A Crown of Swords The Wheel of Time

The Wheel of Time Towers of Midnight

Towers of Midnight Conan Chronicles 2

Conan Chronicles 2 Conan the Magnificent

Conan the Magnificent New Spring

New Spring What the Storm Means

What the Storm Means A Memory of Light twot-14

A Memory of Light twot-14 New Spring: The Novel

New Spring: The Novel Towers of midnight wot-13

Towers of midnight wot-13 A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14

A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14 A Crown of Swords twot-7

A Crown of Swords twot-7 Lord of Chaos twot-6

Lord of Chaos twot-6 The Great Hunt twot-2

The Great Hunt twot-2 The Shadow Rising twot-4

The Shadow Rising twot-4![Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/03/wheel_of_time-11_knife_of_dreams_preview.jpg) Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams

Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams The Dragon Reborn twot-3

The Dragon Reborn twot-3 The Wheel of Time Companion

The Wheel of Time Companion The Fires of Heaven twot-5

The Fires of Heaven twot-5 Prologue to Towers of Midnight

Prologue to Towers of Midnight The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8

The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8 The Path of Daggers twot-8

The Path of Daggers twot-8 By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light

By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light Crossroads of Twilight twot-10

Crossroads of Twilight twot-10 The Gathering Storm twot-12

The Gathering Storm twot-12 Winter's Heart twot-9

Winter's Heart twot-9 Knife of Dreams twot-11

Knife of Dreams twot-11 New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)

New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)