- Home

- Robert Jordan

Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams Page 25

Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams Read online

Page 25

Ordering the canvas wall erected in the clearing, near to the river to make watering the animals easier, the man strutted into the village wearing coat and cloak red enough to make Mat's eyes hurt and so embroidered with golden stars and comets that a Tinker would have wept for the shame of donning the garments. The huge blue-and-red banner was stretched across the entrance, each wagon in its place, the performing platforms unloaded and the wall nearly all up by the time he returned escorting three men and three women. The village was not all that far from Ebou Dar, yet their clothing might have come from another country altogether. The men wore short wool coats in bright colors embroidered with angular scrollwork along the shoulders and sleeves, and dark, baggy trousers stuffed into knee boots. The women, their hair in a sort of coiled bun atop their heads, wore dresses nearly as colorful as Luca's garments, their narrow skirts resplendent with flowers from hem to hips. They did all carry long belt knives, though with straight blades for the most part, and caressed the hilts whenever anybody looked at them: that much was the same. Altara was Altara when it came to touchiness. These were the village Mayor, the four innkeepers. and a lean, leathery, white-haired woman in red: the others addressed her respectfully as Mother. Since the round-bellied Mayor was as white-haired as she, not to mention mostly bald, and none of the innkeepers lacked at least a little gray hair. Mat decided she must be the village Wisdom. He smiled and tipped his hat to her as she passed, and she gave him a sharp look and sniffed in near perfect imitation of Nynaeve. Oh, yes, a Wisdom all right.

Luca showed them around with wide smiles and expansive gestures. elaborate bows and flourishes of his cloak, stopping here and there to make a juggler or a team of acrobats perform a little for his guests, but his smile turned to a sour grimace once they were safely back on their way and out of sight. "Free admission for them and their husbands and wives and all the children," he growled to Mat. "and I'm supposed to pack up if a merchant comes down the road. They weren't that blunt, but they were clear enough, especially that Mother Dar-vale. As if this flyspeck ever attracted enough merchants to fill this field. Thieves and scoundrels, Cauthon. Country folk are all thieves and scoundrels, and an honest man like me is at their mercy."

Soon enough he was toting up what he might earn there despite the complimentary admissions, but he never did give over complaining entirely, even when the line at the entrance stretched nearly as far as it had in Jurador. He just added complaining about how much he would have taken in with another three or four days at the salt town. It was three or four more days. now. and likely he would have lingered until the crowds had dwindled to nothing. Maybe those three Sean-chan had been ta'veren work. Not likely, but it was a pleasant way to think of it. Now that it was all in the past, it was.

That was how they progressed. At best a mere two leagues or perhaps three at an unhurried pace, and usually Luca would find a small town or a cluster of villages that he felt called for a halt. Or better to say that he felt their silver calling to him. Even if they passed nothing but flyspecks not worth the labor of erecting the wall, they never made as much as four leagues before Luca called a halt. He was not about to risk having to camp strung out along the road. If there was not to be a show, Luca liked to find a clearing where the wagons could be parked without too much crowding, though if driven to it, he would dicker with a farmer for the right to stop in an unused pasture. And mutter over the expense the whole next day if it cost no more than a silver penny. He was tight with his purse strings, Luca was.

Trains of merchants' wagons passed them in both directions, making good speed and managing to raise small clouds of dust from the hard-packed road. Merchants wanted to get their goods to market as quickly as possible. Now and then they saw a caravan of Tinkers, too, their boxy wagons as bright as anything in the show except for Luca's wagon. All of them were headed toward Ebou Dar, oddly enough, but then, they moved as slowly as Luca. Not likely any coming the other way would overtake the show. Two or three leagues a day, and the dice rattled away so that Mat was always wondering what lay beyond the next bend in the road or what was catching him up from behind. It was enough to give a man hives.

The very first night, outside Runnien Crossing, he approached Aludra. Near her bright blue wagon she had set up a small canvas enclosure, eight feet tall, for launching her nightflowers, and she straightened with a glare when he pulled back a flap and ducked in. A closed lantern sitting on the ground near the wall gave enough light for him to see that she was holding a dark ball the size of a large melon. Runnien Crossing was only big enough to merit a single nightflower. She opened her mouth, all set to chivvy him out. Not even Luca was allowed in here.

"Lofting tubes." he said quickly, gesturing to the metal-bound wooden tube, as tall as he was and near enough a foot across, sitting upright in front of her on a broad wooden base. "That's why you want a bellfounder. To make lofting tubes from bronze. It's the why I can't puzzle out." It seemed a ridiculous idea—with a little effort, two men could lift one of her wooden lofting tubes into the wagon that carried them and her other supplies; a bronze lofting tube would require a derrick—but it was the only thing that had occurred to him.

With the lantern behind her, shadows hid her expression, but she was silent for a long moment. "Such a clever young man," she said finally. Her beaded braids clicked softly as she shook her head. Her laugh was low and throaty. "Me, I should watch my tongue. I always get into the trouble when I make promises to clever young men. Never think I will tell you the secrets that would make you blush, though, not now. You are already juggling two women, it seems, and me, I will not be juggled."

"Then I'm right?" He was barely able to keep the incredulity from his voice.

"You are," she said. And casually tossed the nightflower at him!

He caught it with a startled oath, and only dared to breathe when he was sure he had a good grip. The covering seemed to be stiff leather, with a tiny stub of fuse sticking out of one side. He had a little familiarity with smaller fireworks, and supposedly those only exploded from fire or if you let air touch what was inside—though he had cut one open once without it going off—yet who could say what might make a nightflower erupt? The firework he had opened had been small enough to hold in one hand. Something the size of this nightflower would likely blow him and Aludra to scraps.

Abruptly he felt foolish. She was not very likely to go throwing the thing if dropping it was dangerous. He began tossing the ball from hand to hand. Not to make up for gasping and all that. Just for something to do.

"How will casting lofting tubes from bronze make them a better weapon?" That was what she wanted, weapons to use against the Sean-chan, to repay them for destroying the Guild of Illuminators. "They seem fearsome enough to me already."

Aludra snatched the nightflower back muttering about clumsy oafs and turning the ball over in her hands to examine the leather surface. Maybe it was not so safe as he had assumed. "A proper lofting tube." she said once she was sure he had not damaged the thing, "it will send this close to three hundred paces straight up into the sky with the right charge, and a longer distance across the ground if the tube is tilted at an angle. But not far enough for what I have in mind. A lofting charge big enough to send it further would burst the tube. With a bronze tube. I could use a charge that would send something a little smaller close to two miles. Making the slow-match slower, to let it travel that far, is easy enough. Smaller but heavier, made of iron, and there would be nothing for pretty colors, only the bursting charge."

Mat whistled through his teeth, seeing it in his head, explosions erupting among the enemy before they were near enough to see you clearly. A nasty thing to be receiving. Now that would be as good as having Aes Sedai on your side, or some of those Asha'man. Better. Aes Sedai had to be in danger to use the Power as a weapon, and while he had heard rumors about hundreds of Asha'man, rumors grew with every telling. Besides, if Asha'man were anything like Aes Sedai, they would start deciding where they were needed and then take

over the whole fight. He began envisioning how to use Aludra's bronze tubes, and right away he spotted a glaring problem. All your advantage was gone if the enemy came from the wrong direction, or got behind you, and if you needed derricks to move these things. . . . "These bronze lofting tubes—'

"Dragons," she broke in. "Lofting tubes are for making the night-flowers bloom. For delighting the eye. I will call them dragons, and the Seanchan will howl when my dragons bite." Her tone was grim as sharp stone.

"These dragons, then. Whatever you call them, they'll be heavy and hard to move. Can you mount them on wheels? Like a wagon or cart? Would they be too heavy for horses to pull?"

She laughed again. "It's good to see you are more than the pretty face." Climbing a three-step folding ladder that put her waist nearly level with the top of the lofting tube, she set the nightflower into the tube with the fuse down. It slid in a little way and stopped, a dome above the top of the tube. "Hand me that," she told him, gesturing to a pole as long and thick as a quarterstaff. When he handed it up to her, she held it upright and used a leather cap on one end to push the nightflower deeper. That appeared to take little effort. "I have already drawn plans for the dragoncarts. Four horses could draw one easily, along with a second cart to hold the eggs. Not nightflowers. Dragons' eggs. You see, I have thought long and hard about how to use my dragons, not just how to make them.' Pulling the capped rod from the tube, she climbed down and picked up the lantern. "Come. I must make the sky bloom a little, then I want my supper and my bed."

Just outside the canvas enclosure stood a wooden rack filled with more peculiar implements, a forked stick, tongs as long as Mat was tall, other things just as odd and all made of wood. Setting the lantern on the ground, she placed the capped pole in the rack and took a square wooden box from a shelf. "I suppose now you want to learn how to make the secret powders, yes? Well. I did promise. I am the Guild, now," she added bitterly, removing the box's lid. It was an odd box. a solid piece of wood drilled with holes, each of which held a thin stick. She plucked out one and replaced the lid. "I can decide what is secret."

"Better than that, I want you to come with me. I know somebody who'll be happy to pay for making as many of your dragons as you want. He can make every bellfounder from Andor to Tear stop casting bells and start casting dragons." Avoiding Rand's name did not stop the colors from whirling inside his head and resolving for an instant into Rand—fully clothed, thank the Light—talking with Loial by lamplight in a wood-paneled room. There were other people, but the image focused on Rand, and it vanished too quickly for Mat to make out who they were. He was pretty sure that what he saw was what was actually happening right that moment, impossible as that seemed. It would be good to see Loial again, but burn him. there had to be some way to keep those things out of his head! "And if he isn't interested." again the colors came, but he resisted, and they melted away. "I can pay to have hundreds cast myself. A lot of them, anyway."

The Band was going to end up fighting Seanchan, and most likely Trollocs as well. And he would be there when it happened. There was no getting around the fact. Try to avoid it how he would, that bloody ta'veren twisting would put him right in the bloody middle. So he was ready to pour out gold like water if it gave him a way to kill his enemies before they got close enough to poke holes in his hide.

Aludra tilted her head to one side, pursing her rosebud lips. "Who is this man with such power?"

"It'll have to be a secret between us. Thorn and Juilin know, and Egeanin and Domon, and the Aes Sedai, Teslyn and Joline at least, and Van in and the Redarms, but nobody else, and I want to keep it that way." Blood and bloody ashes, far too many people knew already. He waited for her curt nod before saying, "The Dragon Reborn." The colors swirled and despite his fighting them again became Rand and Loial for a moment. This was not going to be as easy as it had seemed.

"You know the Dragon Reborn." she said doubtfully.

"We grew up in the same village," he growled, already fighting the colors. This time, they nearly coalesced before vanishing. "If you don't believe me. ask Teslyn and Joline. Ask Thorn. But don't do it around anyone else. A secret, remember."

"The Guild has been my life since I was a girl." She scraped one of the sticks quickly down the side of the box, and the thing sputtered into flame! It smelled of sulphur. "The dragons, they are my life now. The dragons, and revenge on the Seanchan." Bending, she touched the flame to a dark length of fuse that ran under the canvas. As soon as the fuse caught, she shook the stick until the fire went out, then dropped it. With a crackling hiss the flame sped along the fuse. "I think me I believe you." She held out her free hand. "When you leave, I will go with you. And you will help me make many dragons."

For a moment, as he shook her hand, he was sure the dice had stopped, but a heartbeat later they were rattling again. It must have been imagination. After all, this agreement with Aludra might help the Band, and incidentally Mat Cauthon. stay alive, yet it could hardly be called fateful. He would still have to fight those battles, and however you planned, however well-trained your men were, luck played its part, too. bad as well as good, even for him. These dragons would not change that. But were the dice bouncing as loudly? He thought not, yet how could he be sure? Never before had they slowed without stopping. It had to be his imagination.

A hollow thump came from inside the enclosure, and acrid smoke billowed over the canvas wall. Moments later the nightflower bloomed in the darkness above Runnien Crossing, a great ball of red and green streaks. It bloomed again and again in his dreams that night and for many nights after, but there it bloomed among charging horsemen and massed pikes, rending flesh as he had once seen stone rent by fireworks. In his dreams, he tried to catch the things with his hands, tried to stop them, yet they rained down in unending streams on a hundred battlefields. In his dreams, he wept for the death and destruction. And somehow it seemed that the rattling of the dice in his head sounded like laughter. Not his laughter. The Dark One's laughter.

The next morning, with the sun just rising toward a cloudless sky, he was sitting on the steps of his green wagon, carefully scraping at the bowstave with a sharp knife—you had to be careful, almost delicate: a careless slice could ruin all your work—when Egeanin and Domon came out. Strangely, they seemed to have dressed with special care, in their best, such as it was. He was not the only one to have bought cloth in Jurador, but without promises of Mat's gold to speed them, the seamstresses were still sewing for Domon and Egeanin. The blue-eyed Seanchan woman wore a bright green dress heavily embroidered with tiny white and yellow flowers on the high neck and all down the sleeves. A flowered scarf held her long black wig in place. Domon, looking decidedly odd with a head of very short hair and that Illianer beard that left his upper lip bare, had brushed his worn brown coat till it actually had some semblance of neatness. They squeezed past Mat and hurried off without a word, and he thought no more of it until they returned an hour or so later to announce that they had been into the village and gotten Mother Darvale to marry them.

He could not stop himself from gaping. Egeanin's stern face and sharp eyes gave good indications of her character. What could have brought Domon to marry the woman? As soon marry a bear. Realizing the Illianer was beginning to glare at him, he hastily got to his feet and made a presentable bow over the bowstave. "Congratulations, Master Domon. Congratulations. Mistress Domon. The Light shine on you both." What else was he to say?

Domon kept glaring as if he had heard Mat's thoughts, though, and Egeanin snorted. "My name is Leilwin Shipless, Cauthon," she drawled. "That's the name I was given and the name I'll die with. And a good name it is, since it helped me reach a decision I should have made weeks ago." Frowning, she looked sideways at Domon. "You do understand why I could not take your name, don't you, Bayle?"

"No, lass," Domon replied gently, resting a thick hand on her shoulder, "but I will take you with any name you do care to use so long as you be my wife. I told you that." She smiled and laid her hand atop hi

s, and he began smiling, too. Light, but the pair of them were sickening. If marriage made a man start smiling like dreamy syrup. . . . Well, not Mat Cauthon. He might be as good as wed, but Mat Cauthon was never going to start carrying on like a loon.

And that was how he ended up in a green-striped wall-tent, not very large, that belonged to a pair of lean Domani brothers who ate fire and swallowed swords. Even Thom admitted that Balat and Abar were good, and they were popular with the other performers, so finding them places to stay was easy, but that tent cost as much as the wagon had! Everybody knew he had gold to fling about, and that pair just sighed over giving up their snug home when he tried to bargain them down. Well, a new bride and groom needed privacy, and he was more than glad to give it to them if it meant he did not have to watch them go moon-eyed at each other. Besides, he was tired of taking his turn sleeping on the floor. In the tent, at least he had his own cot every night—narrow and hard it might be, yet it was softer than floorboards—and with only him, he had more room than in the wagon even after the rest of his clothes were moved in and stowed in a pair of brass-bound chests. He had a washstand of his very own, a ladder-back chair that was not too unsteady, a sturdy stool, and a table big enough to hold a plate and cup and a pair of decent brass lamps. The chest of gold he left in the green wagon. Only a blind fool would try robbing Domon. Only a madman would try robbing Egeanin. Leilwin. if she insisted, though he was still certain she would regain her senses eventually. After the first night, spent close by the Aes Sedai wagon, with the foxhead cool for half the night, he had the tent set up facing Tuon's wagon by dint of making sure that the Redarms started raising it before anyone else could claim the space.

Conan the Unconquered

Conan the Unconquered Conan the Triumphant

Conan the Triumphant The Eye of the World

The Eye of the World The Great Hunt

The Great Hunt Conan the Victorious

Conan the Victorious The Dragon Reborn

The Dragon Reborn The Fires of Heaven

The Fires of Heaven Winter's Heart

Winter's Heart Lord of Chaos

Lord of Chaos The Shadow Rising

The Shadow Rising Conan the Defender

Conan the Defender The Strike at Shayol Ghul

The Strike at Shayol Ghul The Path of Daggers

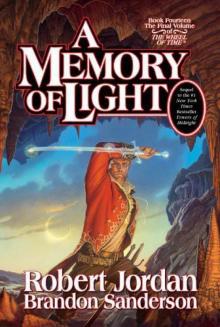

The Path of Daggers A Memory of Light

A Memory of Light Knife of Dreams

Knife of Dreams Crossroads of Twilight

Crossroads of Twilight Conan the Invincible

Conan the Invincible The Gathering Storm

The Gathering Storm Warrior of the Altaii

Warrior of the Altaii A Crown of Swords

A Crown of Swords The Wheel of Time

The Wheel of Time Towers of Midnight

Towers of Midnight Conan Chronicles 2

Conan Chronicles 2 Conan the Magnificent

Conan the Magnificent New Spring

New Spring What the Storm Means

What the Storm Means A Memory of Light twot-14

A Memory of Light twot-14 New Spring: The Novel

New Spring: The Novel Towers of midnight wot-13

Towers of midnight wot-13 A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14

A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14 A Crown of Swords twot-7

A Crown of Swords twot-7 Lord of Chaos twot-6

Lord of Chaos twot-6 The Great Hunt twot-2

The Great Hunt twot-2 The Shadow Rising twot-4

The Shadow Rising twot-4![Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/03/wheel_of_time-11_knife_of_dreams_preview.jpg) Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams

Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams The Dragon Reborn twot-3

The Dragon Reborn twot-3 The Wheel of Time Companion

The Wheel of Time Companion The Fires of Heaven twot-5

The Fires of Heaven twot-5 Prologue to Towers of Midnight

Prologue to Towers of Midnight The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8

The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8 The Path of Daggers twot-8

The Path of Daggers twot-8 By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light

By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light Crossroads of Twilight twot-10

Crossroads of Twilight twot-10 The Gathering Storm twot-12

The Gathering Storm twot-12 Winter's Heart twot-9

Winter's Heart twot-9 Knife of Dreams twot-11

Knife of Dreams twot-11 New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)

New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)