- Home

- Robert Jordan

The Dragon Reborn Page 4

The Dragon Reborn Read online

Page 4

Uno’s eye narrowed until it looked like the pritchel hole of an anvil; with the red painted eye on his patch, it gave him a villainous look. “Cowards, Masema?” he said softly. “If you were a woman, would you have the flaming nerve to ride up here, alone and bloody unarmed?” There was no doubt she would be unarmed if she was of the Tuatha’an. Masema kept his mouth shut, but the scar on his cheek stood out tight and pale.

“Burn me, if I would,” Ragan said. “And burn me if you would either, Masema.” Masema hitched at his cloak and ostentatiously searched the sky.

Uno snorted. “The Light send that flaming carrion eater was flaming alone,” he muttered.

Slowly the shaggy brown-and-white mare meandered closer, picking a way along the clear ground between broad snowbanks. Once the brightly clad woman stopped to peer at something on the ground, then tugged the cowl of her cloak further over her head and heeled her mount forward in a slow walk. The raven, Perrin thought. Stop looking at that bird and come on, woman. Maybe you’ve brought the word that finally takes us out of here. If Moiraine means to let us leave before spring. Burn her! For a moment he was not sure whether he meant the Aes Sedai, or the Tinker woman who seemed to be taking her own time.

If she kept on as she was, the woman would pass a good thirty paces to one side of the thicket. With her eyes fixed on where her piebald stepped, she gave no sign that she had seen them among the trees.

Perrin nudged the stallion’s flanks with his heels, and the dun leaped ahead, sending up sprays of snow with his hooves. Behind him, Uno quietly gave the command, “Forward!”

Stepper was halfway to her before she seemed to become aware of them, and then she jerked her mare to a halt with a start. She watched as they formed an arc centered on her. Embroidery of eye-wrenching blue, in the pattern called a Tairen maze, made her red cloak even more garish. She was not young—gray showed thick in her hair where it was not hidden by her cowl—but her face had few lines, other than the disapproving frown she ran over their weapons. If she was alarmed at meeting armed men in the heart of mountain wilderness, though, she gave no sign. Her hands rested easily on the high pommel of her worn but well-kept saddle. And she did not smell afraid.

Stop that! Perrin told himself. He made his voice soft so as not to frighten her. “My name is Perrin, good mistress. If you need help, I will do what I can. If not, go with the Light. But unless the Tuatha’an have changed their ways, you are far from your wagons.”

She studied them a moment more before speaking. There was a gentleness in her dark eyes, not surprising in one of the Traveling People. “I seek an . . . a woman.”

The skip was small, but it was there. She sought not any woman, but an Aes Sedai. “Does she have a name, good mistress?” Perrin asked. He had done this too many times in the last few months to need her reply, but iron was spoiled for want of care.

“She is called. . . . Sometimes, she is called Moiraine. My name is Leya.”

Perrin nodded. “We will take you to her, Mistress Leya. We have warm fires, and with luck something hot to eat.” But he did not lift his reins immediately. “How did you find us?” He had asked before, each time Moiraine sent him out to wait at a spot she named, for a woman she knew would come. The answer would be the same as it always was, but he had to ask.

Leya shrugged and answered hesitantly. “I . . . knew that if I came this way, someone would find me and take me to her. I . . . just . . . knew. I have news for her.”

Perrin did not ask what news. The women gave the information they brought only to Moiraine.

And the Aes Sedai tells us what she chooses. He thought. Aes Sedai never lied, but it was said that the truth an Aes Sedai told you was not always the truth you thought it was. Too late for qualms, now. Isn’t it?

“This way, Mistress Leya,” he said, gesturing up the mountain. The Shienarans, with Uno at their head, fell in behind Perrin and Leya as they began to climb. The Borderlanders still studied the sky as much as the land, and the last two kept a special watch on their backtrail.

For a time they rode in silence except for the sounds the horses’ hooves made, sometimes crunching through old snowcrust, sometimes sending rocks clattering as they crossed bare stretches. Now and again Leya cast glances at Perrin, at his bow, his axe, his face, but she did not speak. He shifted uncomfortably under the scrutiny, and avoided looking at her. He always tried to give strangers as little chance to notice his eyes as he could manage.

Finally he said, “I was surprised to see one of the Traveling People, believing as you do.”

“It is possible to oppose evil without doing violence.” Her voice held the simplicity of someone stating an obvious truth.

Perrin grunted sourly, then immediately muttered an apology. “Would it were as you say, Mistress Leya.”

“Violence harms the doer as much as the victim,” Leya said placidly. “That is why we flee those who harm us, to save them from harm to themselves as much for our own safety. If we do violence to oppose evil, soon we would be no different from what we struggle against. It is with the strength of our belief that we fight the Shadow.”

Perrin could not help snorting. “Mistress, I hope you never have to face Trollocs with the strength of your belief. The strength of their swords will cut you down where you stand.”

“It is better to die than to—” she began, but anger made him speak right over her. Anger that she just would not see. Anger that she really would die rather than harm anyone, no matter how evil.

“If you run, they will hunt you, and kill you, and eat your corpse. Or they might not wait till it is a corpse. Either way, you are dead, and it’s evil that has won. And there are men just as cruel. Darkfriends and others. More others than I would have believed even a year ago. Let the Whitecloaks decide you Tinkers don’t walk in the Light and see how many of you the strength of your belief can keep alive.”

She gave him a penetrating look. “And yet you are not happy with your weapons.”

How did she know that? He shook his head irritably, shaggy hair swaying. “The Creator made the world,” he muttered, “not I. I must live the best I can in the world the way it is.”

“So sad for one so young,” she said softly. “Why so sad?”

“I should be watching, not talking,” he said curtly. “You won’t thank me if I get you lost.” He heeled Stepper forward enough to cut off any further conversation, but he could feel her looking at him. Sad? I’m not sad, just. . . . Light, I don’t know. There ought to be a better way, that’s all. The itching tickle came again at the back of his head, but absorbed in ignoring Leya’s eyes on his back, he ignored that, too.

Over the slope of the mountain and down they rode, across a forested valley with a broad stream running cold along its bottom, knee-deep on the horses. In the distance, the side of a mountain had been carved into the semblance of two towering forms. A man and a woman, Perrin thought they might be, though wind and rain had long since made that uncertain. Even Moiraine claimed to be unsure who they were supposed to be, or when the granite had been cut.

Pricklebacks and small trout darted away from the horses’ hooves, silver flashes in the clear water. A deer raised its head from browsing, hesitated as the party rode up out of the stream, then bounded off into the trees, and a large mountain cat, gray striped and spotted with black, seemed to rise out of the ground, frustrated in its stalk. It eyed the horses a moment, and with a lash of its tail vanished after the deer. But there was little life visible in the mountains yet. Only a handful of birds perched on limbs or pecked at the ground where the snow had melted. More would return to the heights in a few weeks, but not yet. They saw no other ravens.

It was late afternoon by the time Perrin led them between two steep-sloped mountains, snowy peaks as ever wrapped in cloud, and turned up a smaller stream that splashed downward over gray stones in a series of tiny waterfalls. A bird called in the trees, and another answered it from ahead.

Perrin smiled. Bluefinch calls. A

Borderland bird. No one rode this way without being seen. He rubbed his nose, and did not look at the tree the first “bird” had called from.

Their path narrowed as they rode up through scrubby leatherleaf and a few gnarled mountain oaks. The ground level enough to ride beside the stream became barely wider than a man on horseback, and the stream itself no more than a tall man could step across.

Perrin heard Leya behind him, murmuring to herself. When he looked over his shoulder, she was casting worried glances up the steep slopes to either side. Scattered trees perched precariously above them. It appeared impossible they would not fall. The Shienarans rode easily, at last beginning to relax.

Abruptly a deep, oval bowl between the mountains opened out before them, its sides steep but not nearly so precipitous as the narrow passage. The stream rose from a small spring at its far end. Perrin’s sharp eyes picked out a man with the topknot of a Shienaran, up in the limbs of an oak to his left. Had a redwinged jay called instead of a bluefinch, he would not have been alone, and the way in would not have been so easy. A handful of men could hold that passage against an army. If an army came, a handful would have to.

Among the trees around the bowl stood log huts, not readily visible, so that those gathered around the cook fires at the bottom of the bowl seemed at first to be without shelter. There were fewer than a dozen in sight. And not many more out of sight, Perrin knew. Most of them looked around at the sound of horses, and some waved. The bowl seemed filled with the smells of men and horses, of cooking and burning wood. A long white banner hung limply from a tall pole near them. One form, at least half again as tall as anyone else, sat on a log engrossed in a book that was small in his huge hands. That one’s attention never wavered, even when the only other person without a topknot shouted, “So you found her, did you? I thought you’d be gone the night, this time.” It was a young woman’s voice, but she wore a boy’s coat and breeches and had her hair cut short.

A burst of wind swirled into the bowl, making cloaks flap and rippling the banner out to its full length. For a moment the creature on it seemed to ride the wind. A four-legged serpent scaled in gold and scarlet, golden maned like a lion, and its feet each tipped with five golden claws. A banner of legend. A banner most men would not know if they saw it, but would fear when they learned its name.

Perrin waved a hand that took it all in as he led the way down into the bowl. “Welcome to the camp of the Dragon Reborn, Leya.”

CHAPTER

2

Saidin

Face expressionless, the Tuatha’an woman stared at the banner as it drooped again, then turned her attention to those around the fire. Especially the one reading, the one half again as tall as Perrin and twice as big. “You have an Ogier with you. I would not have thought. . . .” She shook her head. “Where is Moiraine Sedai?” It seemed the Dragon banner might as well not exist as far as she was concerned.

Perrin gestured toward the rough hut that stood furthest up the slope, at the far end of the bowl. With walls and sloping roof of unpeeled logs, it was the largest, though not very big at that. Perhaps just barely large enough to be called a cabin rather than a hut. “That one is hers. Hers and Lan’s. He is her Warder. When you have had something hot to drink—”

“No. I must speak to Moiraine.”

He was not surprised. All the women who came insisted on speaking to Moiraine immediately, and alone. The news that Moiraine chose to share with the rest of them did not always seem very important, but the women held the intensity of a hunter stalking the last rabbit in the world for his starving family. The half-frozen old beggar woman had refused blankets and a plate of hot stew and tramped up to Moiraine’s hut, barefoot in still-falling snow.

Leya slid from her saddle and handed the reins up to Perrin. “Will you see that she is fed?” She patted the piebald mare’s nose. “Piesa is not used to carrying me over such rugged country.”

“Fodder is scarce, still,” Perrin told her, “but she’ll have what we can give her.”

Leya nodded, and went hurrying away up the slope without another word, holding her bright green skirts up, the blue-embroidered red cloak swaying behind her.

Perrin swung down from his saddle, exchanging a few words with the men who came from the fires to take the horses. He gave his bow to the one who took Stepper. No, except for one raven, they had seen nothing but the mountains and the Tuatha’an woman. Yes, the raven was dead. No, she had told them nothing of what was happening outside the mountains. No, he had no idea whether they would be leaving soon.

Or ever, he added to himself. Moiraine had kept them there all winter. The Shienarans did not think she gave the orders, not here, but Perrin knew that Aes Sedai somehow always seemed to get their way. Especially Moiraine.

Once the horses were led away to the rude log stable, the riders went to warm themselves. Perrin tossed his cloak back over his shoulders and held his hands out to the flames gratefully. The big kettle, Baerlon work by the look of it, gave off smells that had been making his mouth water for some time already. Someone had been lucky hunting today, it seemed, and lumpy roots circled another fire close by, giving off an aroma faintly like turnips as they roasted. He wrinkled his nose and concentrated on the stew. More and more he wanted meat above anything else.

The woman in men’s clothes was peering toward Leya, who was just disappearing into Moiraine’s hut.

“What do you see, Min?” he asked.

She came to stand beside him, her dark eyes troubled. He did not understand why she insisted on breeches instead of skirts. Perhaps it was because he knew her, but he could not see how anyone could look at her and see a too-handsome youth instead of a pretty young woman.

“The Tinker woman is going to die,” she said softly, eyeing the others near the fires. None was close enough to hear.

He was still, thinking of Leya’s gentle face. Ah, Light! Tinkers never harm anyone! He felt cold despite the warmth of the fire. Burn me, I wish I’d never asked. Even the few Aes Sedai who knew of it did not understand what Min did. Sometimes she saw images and auras surrounding people, and sometimes she even knew what they meant.

Masuto came to stir the stew with a long wood spoon. The Shienaran eyed them, then laid a finger alongside his long nose and grinned widely before he left.

“Blood and ashes!” Min muttered. “He’s probably decided we are sweethearts murmuring to each other by the fire.”

“Are you sure?” Perrin asked. She raised her eyebrows at him, and he hastily added, “About Leya.”

“Is that her name? I wish I didn’t know. It always makes it worse, knowing and not being able to. . . . Perrin, I saw her own face floating over her shoulder, covered in blood, eyes staring. It’s never any clearer than that.” She shivered and rubbed her hands together briskly. “Light, but I wish I saw more happy things. All the happy things seem to have gone away.”

He opened his mouth to suggest warning Leya, then closed it again. There was never any doubt about what Min saw and knew, for good or bad. If she was certain, it happened.

“Blood on her face,” he muttered. “Does that mean she’ll die by violence?” He winced that he said it so easily. But what can I do? If I tell Leya, if I make her believe somehow, she’ll live her last days in fear, and it will change nothing.

Min gave a short nod.

If she’s going to die by violence, it could mean an attack on the camp. But there were scouts out every day, and guards set day and night. And Moiraine had the camp warded, so she said; no creature of the Dark One would see it unless he walked right into it. He thought of the wolves. No! The scouts would find anyone or anything trying to approach the camp. “It’s a long way back to her people,” he said half to himself. “Tinkers wouldn’t have brought their wagons any further than the foothills. Anything could happen between here and there.”

Min nodded sadly. “And there aren’t enough of us to spare even one guard for her. Even if it would do any good.”

She

had told him; she had tried warning people about bad things when, at six or seven, she had first realized not everyone could see what she saw. She would not say more, but he had the impression that her warnings had only made matters worse, when they were believed at all. It took some doing to believe in Min’s viewings until you had proof.

“When?” he said. The word was cold in his ears, and hard as tool steel. I can’t do anything about Leya, but maybe I can figure out whether we’re going to be attacked.

As soon as the word was out of his mouth, she threw up her hands. She kept her voice down, though. “It isn’t like that. I can never tell when something is going to happen. I only know it will, if I even know what I see means. You don’t understand. The seeing doesn’t come when I want it to, and neither does knowing. It just happens, and sometimes I know. Something. A little bit. It just happens.” He tried to get a soothing word in, but she was letting it all out in a flood he could not stem. “I can see things around a man one day and not the next, or the other way ’round. Most of the time, I don’t see anything around anyone. Aes Sedai always have images around them, of course, and Warders, though it’s always harder to say what it means with them than with anyone else.” She gave Perrin a searching look, half squinting. “A few others always do, too.”

“Don’t tell me what you see when you look at me,” he said harshly, then shrugged his heavy shoulders. Even as a child he had been bigger than most of the others, and he had quickly learned how easy it was to hurt people by accident when you were bigger than they. It had made him cautious and careful, and regretful of his anger when he let it show. “I am sorry, Min. I shouldn’t have snapped at you. I did not mean to hurt you.”

She gave him a surprised look. “You didn’t hurt me. Blessed few people want to know what I see. The Light knows, I would not, if it were someone else who could do it.” Even the Aes Sedai had never heard of anyone else who had her gift. “Gift” was how they saw it, even if she did not.

Conan the Unconquered

Conan the Unconquered Conan the Triumphant

Conan the Triumphant The Eye of the World

The Eye of the World The Great Hunt

The Great Hunt Conan the Victorious

Conan the Victorious The Dragon Reborn

The Dragon Reborn The Fires of Heaven

The Fires of Heaven Winter's Heart

Winter's Heart Lord of Chaos

Lord of Chaos The Shadow Rising

The Shadow Rising Conan the Defender

Conan the Defender The Strike at Shayol Ghul

The Strike at Shayol Ghul The Path of Daggers

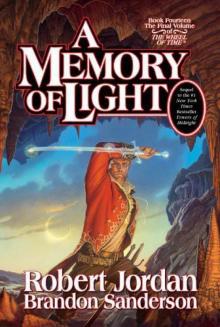

The Path of Daggers A Memory of Light

A Memory of Light Knife of Dreams

Knife of Dreams Crossroads of Twilight

Crossroads of Twilight Conan the Invincible

Conan the Invincible The Gathering Storm

The Gathering Storm Warrior of the Altaii

Warrior of the Altaii A Crown of Swords

A Crown of Swords The Wheel of Time

The Wheel of Time Towers of Midnight

Towers of Midnight Conan Chronicles 2

Conan Chronicles 2 Conan the Magnificent

Conan the Magnificent New Spring

New Spring What the Storm Means

What the Storm Means A Memory of Light twot-14

A Memory of Light twot-14 New Spring: The Novel

New Spring: The Novel Towers of midnight wot-13

Towers of midnight wot-13 A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14

A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14 A Crown of Swords twot-7

A Crown of Swords twot-7 Lord of Chaos twot-6

Lord of Chaos twot-6 The Great Hunt twot-2

The Great Hunt twot-2 The Shadow Rising twot-4

The Shadow Rising twot-4![Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/03/wheel_of_time-11_knife_of_dreams_preview.jpg) Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams

Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams The Dragon Reborn twot-3

The Dragon Reborn twot-3 The Wheel of Time Companion

The Wheel of Time Companion The Fires of Heaven twot-5

The Fires of Heaven twot-5 Prologue to Towers of Midnight

Prologue to Towers of Midnight The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8

The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8 The Path of Daggers twot-8

The Path of Daggers twot-8 By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light

By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light Crossroads of Twilight twot-10

Crossroads of Twilight twot-10 The Gathering Storm twot-12

The Gathering Storm twot-12 Winter's Heart twot-9

Winter's Heart twot-9 Knife of Dreams twot-11

Knife of Dreams twot-11 New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)

New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)