- Home

- Robert Jordan

Towers of midnight wot-13 Page 5

Towers of midnight wot-13 Read online

Page 5

Perhaps he should get some gloves. But if he did, he couldn't cut his hand. What a problem.

No matter. Onward. The time had come to kill al'Thor.

It saddened him that the hunt must end. But there was no longer a reason for a hunt. You didn't hunt something when you knew exactly where it was going to be. You merely showed up to meet it.

Like an old friend. A dear, beloved old friend that you were going to stab through the eye, open up at the gut and consume by handfuls while drinking his blood. That was the proper way to treat friends.

It was an honor.

Malenarin Rai shuffled through supply reports. That blasted shutter on the window behind his desk snapped and blew open again, letting in the damp heat of the Blight.

Despite ten years serving as commander of Heeth Tower, he hadn't grown accustomed to the heat in the highlands. Damp. Muggy, the air often full of rotting scents.

The whistling wind rattled the wooden shutter. He rose, walking over to pull it shut, then twisted a bit of twine around its handle to keep it closed.

He walked back to his desk, looking over the roster of newly arrived soldiers. Each name had a specialty beside it—up here, every soldier had to fill two or more duties. Skill at binding wounds. Swift feet for running messages. A keen eye with a bow. The ability to make the same old mush taste like new mush. Malenarin always asked specifically for men in the last group. Any cook who could make soldiers eager to come to mess was worth his weight in gold.

Malenarin set aside his current report, weighing it down with the lead-filled Trolloc horn he kept for the purpose. The next sheet in his stack was a letter from a man named Barriga, a merchant who was bringing his caravan to the tower to trade. Malenarin smiled; he was a soldier first, but he wore the three silver chains across his chest that marked him as a master merchant. While his tower received many of its supplies directly from the Queen, no Kandori commander was denied the opportunity to barter with merchants.

If he was lucky, he'd be able to get this outlander merchant drunk at the bargaining table. Malenarin had forced more than one merchant into a year of military service as penance for entering bargains he could not keep. A year of training with the Queen's forces often did plump foreign merchants a great deal of good.

He set that sheet beneath the Trolloc horn, then hesitated as he saw the last item for his attention at the bottom of the stack. It was a reminder from his steward. Keemlin, his eldest son, was approaching his fourteenth nameday. As if Malenarin could forget about that! He needed no reminder.

He smiled, setting the Trolloc horn on the note, in case that shutter broke open again. He'd slain the Trolloc who had borne that horn himself. Then he walked over to the side of his office and opened his battered oak trunk. Among the other effects inside was a cloth-wrapped sword, the brown scabbard kept well oiled and maintained, but faded with time. His father's sword.

In three days, he would give it to Keemlin. A boy became a man on his fourteenth nameday, the day he was given his first sword and became responsible for himself. Keemlin had worked hard to learn his forms under the harshest trainers Malenarin could provide. Soon his son would become a man. How quickly the years passed.

Taking a proud breath, Malenarin closed the trunk, then rose and left his office for his daily rounds. The tower housed two hundred and fifty soldiers, a bastion of defense that watched the Blight.

To have a duty was to have pride—just as to bear a burden was to gain strength. Watching the Blight was his duty and his strength, and it was particularly important these days, with the strange storm to the north, and with the Queen and much of the Kandori army having marched to seek the Dragon Reborn. He pulled the door to his office closed, then threw the hidden latch that barred it on the other side. It was one of several such doors in the hallway; an enemy storming the tower wouldn't know which one opened onto the stairwell upward. In this way, a small office could function as part of the tower defense.

He walked to the stairwell. These top levels were not accessible from the ground level—the entire bottom forty feet of the tower was a trap. An enemy who entered at the ground floor and climbed up three flights of garrison quarters would discover no way up to the fourth floor. The only way to go to the fourth level was to climb a narrow, collapsible ramp on the outside of the tower that led from the second level up to the fourth. Running on it left attackers fully exposed to arrows from above. Then, once some of them were up but others not, the Kandori would collapse the ramp, dividing the enemy force and leaving those above to be killed as they tried to find the interior stairwells.

Malenarin climbed at a brisk pace. Periodic slits to the sides of the steps looked down on the stairs beneath, and would allow archers to fire on invaders. When he was about halfway to the top, he heard hasty footfalls coming down. A second later, Jargen—sergeant of the watch—rounded the bend. Like most Kandori, Jargen wore a forked beard; his black hair was dusted with gray.

Jargen had joined the Blightwatch the day after his fourteenth nameday. He wore a cord looped around the shoulder of his brown uniform; it bore a knot for each Trolloc he'd killed. There had to be approaching fifty knots in the thing by now.

Jargen saluted with arm to breast, then lowered his hand to rest on his sword, a sign of respect for his commander. In many countries, holding the weapon like that would be an insult, but Southerners were known to be peevish and ill-tempered. Couldn't they see that it was an honor to hold your sword and imply you found your commander a worthy threat?

"My Lord," Jargen said, voice gruff. "A flash from Rena Tower."

"What?" Malenarin asked. The two fell into step, trotting up the stairwell.

"It was distinct, sir," Jargen said. "Saw it myself, I did. Only a flash, but it was there."

"Did they send a correction?"

"They may have by now. I ran to fetch you first."

If there had been more news, Jargen would have shared it, so Malenarin did not waste breath pressing him. Shortly, they stepped up onto the top of the tower, which held an enormous mechanism of mirrors and lamps. With the apparatus, the tower could send messages to the east or west—where other towers lined the Blight—or southward, along a line of towers that ran to the Aesdaishar Palace in Chachin.

The vast, undulating Kandori highlands spread out from his tower. Some of the southern hills were still lightly laced with morning fog. That land to the south, free of this unnatural heat, would soon grow green, and Kandori herdsmen would climb to the high pastures to graze their sheep.

Northward lay the Blight. Malenarin had read of days when the Blight had barely been visible from this tower. Now it ran nearly to the base of the stonework. Rena Tower was northwest as well. Its commander—Lord Niach of House Okatomo—was a distant cousin and a good friend. He would not have sent a flash without reason, and would send a retraction if it had been an accident.

"Any further word?" Malenarin asked.

The soldiers on watch shook their heads. Jargen tapped his foot, and Malenarin folded his arms to wait for a correction.

Nothing came. Rena Tower stood within the Blight these days, as it was farther north than Heeth Tower. Its position within the Blight was normally not an issue. Even the most fearsome creatures of the Blight knew not to attack a Kandori tower.

No correction came. Not a glimmer. "Send a message to Rena," Malenarin said. "Ask if their flash was a mistake. Then ask Farmay Tower if they have noticed anything strange."

Jargen set the men to work, but gave Malenarin a flat glance, as if to ask, "You think I haven't done that already?"

That meant messages had been sent, but there was no word back. Wind blew across the tower top, creaking the steel of the mirror apparatus as his men sent another series of flashes. That wind was humid. Far too hot. Malenarin glanced upward, toward where that same black storm boiled and rolled. It seemed to have settled down.

That struck him as very discomforting.

"Flash a message backward," Malenarin said, "to

ward the inland towers. Tell them what we saw; tell them to be ready in case of trouble."

The men set to work.

"Sergeant," Malenarin said, "who is next on the messenger roster?"

The tower force included a small group of boys who were excellent riders. Lightweight, they could go on fast horses should a commander decide to bypass the mirrors. Mirror light was fast, but it could be seen by one's enemies. Besides, if the line of towers was broken—or if the apparatus was damaged—they would need a means to get word to the capital.

"Next on the roster…" Jargen said, checking a list nailed to the inside of the door onto the rooftop. "It would be Keemlin, my Lord."

Keemlin. His Keemlin.

Malenarin glanced to the northwest, toward the silent tower that had flashed so ominously. "Bring me word if there is a hint of response from the other towers," Malenarin said to the soldiers. "Jargen, come with me."

The two of them hurried down the stairs. "We need to send a messenger southward," Malenarin said, then hesitated. "No. No, we need to send several messengers. Double up. Just in case the towers fall." He began moving again.

The two of them left the stairwell and entered Malenarin's office. He grabbed his best quill off the rack on his wall. That blasted shutter was blowing and rattling again; the papers on his desk rustled as he pulled out a fresh sheet of paper.

Rena and Farmay not responding to flash messages. Possibly overrun or severely hampered. Be advised. Heeth will stand.

He folded the paper, holding it up to Jargen. The man took it with a leathery hand, read it over, then grunted. "Two copies, then?"

"Three," Malenarin said. "Mobilize the archers and send them to the roof. Tell them danger may come from above."

If he wasn't merely jumping at shadows—if the towers to either side of Heeth had fallen so quickly—then so could those to the south. And if he'd been the one making an assault, he'd have done anything he could to sneak around and take out one of the southern towers first. That was the best way to make sure no messages got back to the capital.

Jargen saluted, fist to chest, then withdrew. The message would be sent immediately: three times on legs of horseflesh, once on legs of light. Malenarin let himself feel a hint of relief that his son was one of those riding to safety. There was no dishonor in that; the messages needed to be delivered, and Keemlin was next on the roster.

Malenarin glanced out his window. It faced north, toward the Blight. Every commander's office did that. The bubbling storm, with its silvery clouds. Sometimes they looked like straight geometric shapes. He had listened well to passing merchants. Troubled times were coming. The Queen would not have gone south to seek a false Dragon, no matter how cunning or influential he might be. She believed.

It was time for Tarmon Gai'don. And looking out into that storm, Malenarin thought he could see to the very edge of time itself. An edge that was not far distant. In fact, it seemed to be growing darker. And there was a darkness beneath it, on the ground northward.

That darkness was advancing.

Malenarin dashed out of the room, racing up the steps to the roof, where the wind swept against men pushing and moving mirrors.

"Was the message sent to the south?" he demanded.

"Yes, sir," Lieutenant Landalin said. He'd been roused to take command of the tower's top. "No reply yet."

Malenarin glanced down, and picked out three riders breaking away from the tower at full speed. The messengers were off. They would stop at Barklan if it wasn't being attacked. The captain there would send them on southward, just in case. And if Barklan didn't stand, the boys would continue on, all the way to the capital if needed.

Malenarin turned back to the storm. That advancing darkness had him on edge. It was coming.

"Raise the hoardings," he ordered Landalin. "Bring up the store hitchings and empty the cellars. Have the loaders gather all of the arrows and set up stations for resupplying the archers, and put archers at every choke point, kill slit and window. Start the firepots and have men ready to drop the outer ramps. Prepare for a siege."

As Landalin barked orders, men rushed away. Malenarin heard boots scrape stone behind him, and he glanced over his shoulder. Was that Jargen back again?

No. It was a youth of nearly fourteen summers, too young for a beard, his dark hair disheveled, his face streaming with sweat caused—presumably—by a run up seven levels of the tower.

Keemlin. Malenarin felt a stab of fear, instantly replaced with anger. "Soldier! You were to ride with a message!"

Keemlin bit his lip. "Well, sir," he said. "Tian, four places down from me. He is five, maybe ten pounds lighter than I. It makes a big difference, sir. He rides a lot faster, and I figured this would be an important message. So I asked for him to be sent in my place."

Malenarin frowned. Soldiers moved around them, rushing down the stairs or gathering with bows at the rim of the tower. The wind howled outside and thunder began to sound softly—yet insistently.

Keemlin met his eyes. "Tian's mother, Lady Yabeth, has lost four sons to the Blight," he said, softly enough that only Malenarin could hear. "Tian's the only one she has left. If one of us has a shot at getting out, sir, I figured it should be him."

Malenarin held his son's eyes. The boy understood what was coming. Light help him, but he understood. And he'd sent another away in his place.

"Kralle," Malenarin barked, glancing toward one of the soldiers passing by.

"Yes, my Lord Commander?"

"Run down to my office," Malenarin said. "There is a sword in my oaken trunk. Fetch it for me."

The man saluted, obeying.

"Father?" Keemlin said. "My nameday isn't for three days."

Malenarin waited with arms behind his back. His most important task at the moment was to be seen in command, to reassure his troops. Kralle returned with the sword; its worn scabbard bore the image of the oak set aflame. The symbol of House Rai.

"Father…" Keemlin repeated. "I—"

"This weapon is offered to a boy when he becomes a man," Malenarin said. "It seems it is too late in coming, son. For I see a man standing before me." He held the weapon forward in his right hand. Around the tower top, soldiers turned toward him: the archers with bows ready, the soldiers who operated the mirrors, the duty watchmen. As Borderlanders, each and every one of them would have been given his sword on his fourteenth nameday. Each one had felt the catch in the chest, the wonderful feeling of coming of age. It had happened to each of them, but that did not make this occasion any less special.

Keemlin went down on one knee.

"Why do you draw your sword?" Malenarin asked, voice loud so that every man atop the tower would hear.

"In defense of my honor, my family, or my homeland," Keemlin replied.

"How long do you fight?"

"Until my last breath joins the northern winds."

"When do you stop watching?"

"Never," Keemlin whispered.

"Speak it louder!"

"Never!"

"Once this sword is drawn, you become a warrior, always with it near you in preparation to fight the Shadow. Will you draw this blade and join us, as a man?"

Keemlin looked up, then took the hilt in a firm grip and pulled the weapon free.

"Rise as a man, my son!" Malenarin declared.

Keemlin stood, holding the weapon aloft, the bright blade reflecting the diffuse sunlight. The men atop the tower cheered.

It was no shame to find tears in one's eyes at such a moment. Malenarin blinked them free, then knelt down, buckling the sword belt at his son's waist. The men continued to cheer and yell, and he knew it was not only for his son. They yelled in defiance of the Shadow. For a moment, their voices rang louder than the thunder.

Malenarin stood, laying a hand on his son's shoulder as the boy slid his sword into its sheath. Together they turned to face the oncoming Shadow. "There!" one of the archers said, pointing upward. "There's something in the clouds!"

"Draghkar!"

another one said.

The unnatural clouds were close now, and the shade they cast could no longer hide the undulating horde of Trollocs beneath. Something flew out from the sky, but a dozen of his archers let loose. The creature screamed and fell, dark wings flapping awkwardly.

Jargen pushed his way through to Malenarin. "My Lord," Jargen said, shooting a glance at Keemlin, "the boy should be below."

"Not a boy any longer," Malenarin said with pride. "A man. What is your report?"

"All is prepared." Jargen glanced over the wall, eyeing the oncoming Trollocs as evenly as if he were inspecting a stable of horses. "They will not find this tree an easy one to fell."

Malenarin nodded. Keemlin's shoulder was tense. That sea of Trollocs seemed endless. Against this foe, the tower would eventually fall. The Trollocs would keep coming, wave after wave.

But every man atop that tower knew his duty. They'd kill Shadowspawn as long as they could, hoping to buy enough time for the messages to do some good.

Malenarin was a man of the Borderlands, same as his father, same as his son beside him. They knew their task. You held until you were relieved.

That's all there was to it.

CHAPTER 1

Apples First

First The Wheel of Time turns, and Ages come and pass, leaving memories that become legend. Legend fades to myth, and even myth is long forgotten when the Age that gave it birth comes again. In one Age, called the Third Age by some, an Age yet to come, an Age long past, a wind rose above the misty peaks of Imfaral. The wind was not the beginning. There are neither beginnings nor endings to the turning of the Wheel of Time. But it was a beginning.

Crisp and light, the wind danced across fields of new mountain grass stiff with frost. That frost lingered past first light, sheltered by the omnipresent clouds that hung like a death mask high above. It had been weeks since those clouds had budged, and the wan, yellowed grass showed it.

Conan the Unconquered

Conan the Unconquered Conan the Triumphant

Conan the Triumphant The Eye of the World

The Eye of the World The Great Hunt

The Great Hunt Conan the Victorious

Conan the Victorious The Dragon Reborn

The Dragon Reborn The Fires of Heaven

The Fires of Heaven Winter's Heart

Winter's Heart Lord of Chaos

Lord of Chaos The Shadow Rising

The Shadow Rising Conan the Defender

Conan the Defender The Strike at Shayol Ghul

The Strike at Shayol Ghul The Path of Daggers

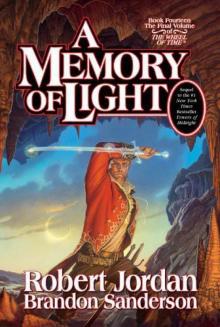

The Path of Daggers A Memory of Light

A Memory of Light Knife of Dreams

Knife of Dreams Crossroads of Twilight

Crossroads of Twilight Conan the Invincible

Conan the Invincible The Gathering Storm

The Gathering Storm Warrior of the Altaii

Warrior of the Altaii A Crown of Swords

A Crown of Swords The Wheel of Time

The Wheel of Time Towers of Midnight

Towers of Midnight Conan Chronicles 2

Conan Chronicles 2 Conan the Magnificent

Conan the Magnificent New Spring

New Spring What the Storm Means

What the Storm Means A Memory of Light twot-14

A Memory of Light twot-14 New Spring: The Novel

New Spring: The Novel Towers of midnight wot-13

Towers of midnight wot-13 A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14

A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14 A Crown of Swords twot-7

A Crown of Swords twot-7 Lord of Chaos twot-6

Lord of Chaos twot-6 The Great Hunt twot-2

The Great Hunt twot-2 The Shadow Rising twot-4

The Shadow Rising twot-4![Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/03/wheel_of_time-11_knife_of_dreams_preview.jpg) Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams

Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams The Dragon Reborn twot-3

The Dragon Reborn twot-3 The Wheel of Time Companion

The Wheel of Time Companion The Fires of Heaven twot-5

The Fires of Heaven twot-5 Prologue to Towers of Midnight

Prologue to Towers of Midnight The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8

The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8 The Path of Daggers twot-8

The Path of Daggers twot-8 By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light

By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light Crossroads of Twilight twot-10

Crossroads of Twilight twot-10 The Gathering Storm twot-12

The Gathering Storm twot-12 Winter's Heart twot-9

Winter's Heart twot-9 Knife of Dreams twot-11

Knife of Dreams twot-11 New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)

New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)