- Home

- Robert Jordan

The Great Hunt Page 62

The Great Hunt Read online

Page 62

“Egwene, Galad is so good he’d make you tear your hair out. He’d hurt a person because he had to serve a greater good. He wouldn’t even notice who was hurt, because he’d be so intent on the other, but if he did, he would expect them to understand and think it was all well and right.”

“I suppose you know,” Egwene said. She had seen Min’s ability to look at people and read all sorts of things about them; Min did not tell everything she saw, and she did not always see anything, but there had been enough for Egwene to believe. She glanced at Nynaeve—the other woman was still pacing, muttering to herself—then reached for saidar again and resumed her juggling in a desultory fashion.

Min shrugged. “I guess I might as well tell you. He didn’t even notice what Else was doing. He asked her if she knew whether you might be walking the South Garden after supper, since today is a freeday. I felt sorry for her.”

“Poor Else,” Egwene murmured, and the balls of light became more lively above her hands. Min laughed.

The door banged open, caught by the wind. Egwene gave a yelp and let the balls vanish before she saw it was only Elayne.

The golden-haired Daughter-Heir of Andor pushed the door shut and hung up her cloak on a peg. “I just heard,” she said. “The rumors are true. King Galldrian is dead. That makes it a war of succession.”

Min snorted. “Civil war. War of succession. A lot of silly names for the same thing. Do you mind if we don’t talk about it? That’s all we hear. War in Cairhien. War on Toman Head. They may have caught the false Dragon in Saldaea, but there’s still war in Tear. Most of it is rumors, anyway. Yesterday, I heard one of the cooks saying she’d heard Artur Hawkwing was marching on Tanchico. Artur Hawkwing!”

“I thought you did not want to talk about it,” Egwene said.

“I saw Logain,” Elayne said. “He was sitting on a bench in the Inner Court, crying. He ran when he saw me. I cannot help feeling sorry for him.”

“Better he cries than the rest of us, Elayne,” Min said.

“I know what he is,” Elayne said calmly. “Or rather, what he was. He isn’t anymore, and I can feel sorry for him.”

Egwene slumped back against the wall. Rand. Logain always made her think of Rand. She had not dreamed about him in months, now, not the kind of dreams she had had on the River Queen. Anaiya still made her write down everything she dreamed, and the Aes Sedai checked them for signs, or connections to events, but there was never anything about Rand except dreams that, Anaiya said, meant she missed him. Oddly, she felt almost as if he were not there any longer, as if he had ceased to exist, along with her dreams, a few weeks after reaching the White Tower. And I sit thinking about how nicely Galad walks, she thought bitterly. Rand has to be all right. If he’d been caught and gentled, I’d have heard something.

That sent a chill through her, as it never failed to do, the thought of Rand being gentled, Rand weeping and wanting to die as Logain did.

Elayne sat down beside her on the bed, tucking her feet up under her. “If you are mooning over Galad, Egwene, you will have no sympathy from me. I’ll have Nynaeve dose you with one of those horrible concoctions she’s always talking about.” She frowned at Nynaeve, who had taken no notice of her entrance. “What is the matter with her? Don’t tell me she has started sighing after Galad, too!”

“I wouldn’t bother her.” Min leaned toward the two of them and lowered her voice. “That skinny Accepted Irella told her she was as clumsy as a cow and had half the Talents, and Nynaeve clouted her ear.” Elayne winced. “Exactly,” Min murmured. “They had her up to Sheriam’s study before you could blink, and she hasn’t been fit to live with since.”

Apparently Min had not dropped her voice enough, for there was a growl from Nynaeve. Suddenly the door whipped open once more, and a gale howled into the room. It did not ruffle the blankets on Egwene’s bed, but Min and the stool toppled, to roll against the wall. Immediately the wind died, and Nynaeve stood with a stricken look on her face.

Egwene hurried to the door and peeked out. The noonday sun was burning off the last reminders of last night’s rainstorm. The still-damp balcony around the Novices’ Court was empty, the long row of doors to novices’ rooms all shut. The novices who had taken advantage of the freeday to enjoy themselves in the gardens were no doubt catching up on their sleep. No one could have seen. She closed the door and took her place beside Elayne again as Nynaeve helped Min to her feet.

“I’m sorry, Min,” Nynaeve said in a tight voice. “Sometimes my temper. . . . I can’t ask you to forgive me, not for this.” She took a deep breath. “If you want to report me to Sheriam, I will understand. I deserve it.”

Egwene wished she had not heard that admission; Nynaeve could grow prickly over such things. Searching for something on which to focus, something Nynaeve could believe she had had her attention on, she found herself touching saidar once more, and began juggling the balls of light again. Elayne quickly joined her; Egwene saw the glow form around the Daughter-Heir even before three tiny balls appeared above her hands. They began to pass the little glowing spheres back and forth in increasingly intricate patterns. Sometimes one winked out as one girl or the other failed to maintain it as it came to her, then winked back a little altered in color or size.

The One Power filled Egwene with life. She smelled the faint rose aroma of soap from Elayne’s morning bath. She could feel the rough plaster of the walls, the smooth stones of the floor, as well as she could the bed where she sat. She could hear Min and Nynaeve breathe, much less their quiet words.

“If it comes to forgiving,” Min said, “maybe you should forgive me. You have a temper, and I have a big mouth. I will forgive you if you forgive me.” With murmurs of “forgiven” that sounded meant on both sides, the two women hugged. “But if you do it again,” Min said with a laugh, “I might clout your ear.”

“Next time,” Nynaeve replied, “I will throw something at you.” She was laughing, too, but her laughter ceased abruptly as her eye fell on Egwene and Elayne. “You two stop that, or there will be someone going to the Mistress of Novices. Two someones.”

“Nynaeve, you wouldn’t!” Egwene protested. When she saw the look in Nynaeve’s eyes, though, she hastily severed all contact with saidar. “Very well. I believe you. There’s no need to prove it.”

“We have to practice,” Elayne said. “They ask more and more of us. If we did not practice on our own, we would never keep up.” Her face showed calm composure, but she had let go of saidar as hastily as Egwene herself had.

“And what happens when you draw too much,” Nynaeve asked, “and there’s no one there to stop you? I wish you were more afraid. I am. Don’t you think I know what it is like for you? It’s always there, and you want to fill yourself with it. Sometimes it is all I can do to make myself stop; I want all of it. I know it would burn me to a crisp, and I want it anyway.” She shivered. “I just wish you were more afraid.”

“I am afraid,” Egwene said with a sigh. “I’m terrified. But it doesn’t seem to help. What about you, Elayne?”

“The only thing that terrifies me,” Elayne said airily, “is washing dishes. It seems as if I have to wash dishes every day.” Egwene threw her pillow at her. Elayne pulled it off her head and threw it back, but then her shoulders slumped. “Oh, very well. I am so scared I don’t know why my teeth are not chattering. Elaida told me I’d be so frightened that I would want to run away with the Traveling People, but I did not understand. A man who drove oxen as hard as they drive us would be shunned. I am tired all the time. I wake up tired and go to bed exhausted, and sometimes I’m so afraid that I will slip and channel more of the Power than I can handle that I. . . .” Peering into her lap, she let the words trail off.

Egwene knew what she had not spoken. Their rooms lay right next to each other, and as in many of the novice rooms, a small hole had long ago been bored through the wall between, too small to be seen unless you knew where to look, but useful for talk after the lamps were extinguished, w

hen the girls could not leave their rooms. Egwene had heard Elayne crying herself to sleep more than once, and she had no doubt that Elayne had heard her own crying.

“The Traveling People are tempting,” Nynaeve agreed, “but wherever you go, it will not change what you can do. You cannot run from saidar.” She did not sound as if she liked what she was saying.

“What do you see, Min?” Elayne said. “Are we all going to be powerful Aes Sedai, or will we spend the rest of our lives washing dishes as novices, or. . . .” She shrugged uncomfortably as if she did not want to voice the third alternative that came to mind. Sent home. Put out of the Tower. Two novices had been put out since Egwene came, and everyone spoke of them in whispers, as if they were dead.

Min shifted on her stool. “I don’t like reading friends,” she muttered. “Friendship gets in the way of the reading. It makes me try to put the best face on what I see. That’s why I don’t do it for you three anymore. Anyway, nothing has changed about you that I can. . . .” She squinted at them, and suddenly frowned. “That’s new,” she breathed.

“What?” Nynaeve asked sharply.

Min hesitated before answering. “Danger. You are all in some kind of danger. Or you will be, very soon. I can’t make it out, but it is danger.”

“You see,” Nynaeve said to the two girls sitting on the bed. “You must take care. We all must. You must both promise not to channel again without someone to guide you.”

“I don’t want to talk about it anymore,” Egwene said.

Elayne nodded eagerly. “Yes. Let’s talk about something else. Min, if you put on a dress, I’ll wager Gawyn would ask you to go walking with him. You know he’s been looking at you, but I think the breeches and the man’s coat put him off.”

“I dress the way I like, and I won’t change for a lord, even if he is your brother.” Min spoke absently, still squinting at them and frowning; it was a conversation they had had before. “Sometimes it is useful to pass as a boy.”

“No one who looks twice believes you are a boy.” Elayne smiled.

Egwene was uncomfortable. Elayne was forcing a semblance of gaiety, Min was hardly paying attention, and Nynaeve looked as if she wanted to warn them again.

When the door swung open once more, Egwene bounded to her feet to close it, grateful for something to do besides watch the others pretend. Before she reached it, though, a dark-eyed Aes Sedai with her blond hair done in a multitude of braids stepped into the room. Egwene blinked in surprise, as much at it being any Aes Sedai as at Liandrin. She had not heard that Liandrin had returned to the White Tower, but beyond that, novices were sent for if an Aes Sedai wanted them; it could mean no good, a sister coming herself.

The room was crowded with five women in it. Liandrin paused to adjust her red-fringed shawl, eyeing them. Min did not move, but Elayne rose, and the three standing curtsied, though Nynaeve barely flexed her knee. Egwene did not think Nynaeve would ever grow used to having others in authority over her.

Liandrin’s eyes settled on Nynaeve. “And why are you here, in the novices’ quarters, child?” Her tone was ice.

“I am visiting with friends,” Nynaeve said in a tight voice. After a moment she added a belated, “Liandrin Sedai.”

“The Accepted, they can have no friends among the novices. This you should have learned by this time, child. But it is as well that I find you here. You and you”—her finger stabbed at Elayne and Min—“will go.”

“I will return later.” Min rose casually, making a great show of being in no hurry to obey, and strolled by Liandrin with a grin, of which Liandrin took no notice at all. Elayne gave Egwene and Nynaeve a worried look before she dropped a curtsy and left.

After Elayne closed the door behind her, Liandrin stood studying Egwene and Nynaeve. Egwene began to fidget under the scrutiny, but Nynaeve held herself straight, with only a little heightening of her color.

“You two are from the same village as the boys who traveled with Moiraine. Is it not so?” Liandrin said suddenly.

“Do you have some word of Rand?” Egwene asked eagerly. Liandrin arched an eyebrow at her. “Forgive me, Aes Sedai. I forget myself.”

“Have you word of them?” Nynaeve said, just short of a demand. The Accepted had no rule about not speaking to an Aes Sedai until spoken to.

“You have concern for them. That is good. They are in danger, and you might be able to help them.”

“How do you know they’re in trouble?” There was no doubt about the demand in Nynaeve’s voice this time.

Liandrin’s rosebud mouth tightened, but her tone did not change. “Though you are not aware of it, Moiraine has sent letters to the White Tower concerning you. Moiraine Sedai, she worries about you, and about your young . . . friends. These boys, they are in danger. Do you wish to help them, or leave them to their fate?”

“Yes,” Egwene said, at the same time that Nynaeve said, “What kind of trouble? Why do you care about helping them?” Nynaeve glanced at the red fringe on Liandrin’s shawl. “And I thought you didn’t like Moiraine.”

“Do not presume too much, child,” Liandrin said sharply. “To be Accepted is not to be a sister. Accepted and novices alike listen when a sister speaks, and do as they are told.” She drew a breath and went on; her tone was coldy serene again, but angry white spots marred her cheeks. “Someday, I am sure, you will serve a cause, and you will learn then that to serve it you must work even with those whom you dislike. I tell you I have worked with many with whom I would not share a room if it were left to me alone. Would you not work alongside the one you hated worst, if it would save your friends?”

Nynaeve nodded reluctantly. “But you still haven’t told us what kind of danger they’re in. Liandrin Sedai.”

“The danger comes from Shayol Ghul. They are hunted, as I understand they once before were. If you will come with me, some dangers, at least, may be eliminated. Do not ask how, for I cannot tell you, but I tell you flatly it is so.”

“We will come, Liandrin Sedai,” Egwene said.

“Come where?” Nynaeve said. Egwene shot her an exasperated look.

“Toman Head.”

Egwene’s mouth fell open, and Nynaeve muttered, “There’s a war on Toman Head. Does this danger have something to do with Artur Hawkwing’s armies?”

“You believe rumors, child? But even if they were true, is that enough to stop you? I thought you called these men friends.” A twist to Liandrin’s words said she would never do the same.

“We will come,” Egwene said. Nynaeve opened her mouth again, but Egwene went right on. “We will go, Nynaeve. If Rand needs our help—and Mat, and Perrin—we have to give it.”

“I know that,” Nynaeve said, “but what I want to know is, why us? What can we do that Moiraine—or you, Liandrin—cannot?”

The white grew in Liandrin’s cheeks—Egwene realized Nynaeve had forgotten the honorific in addressing her—but what she said was, “You two come from their village. In some way I do not entirely understand, you are connected to them. Beyond that, I cannot say. And no more of your foolish questions will I answer. Will you come with me for their sake?” She paused for their assent; a visible tension left her when they nodded. “Good. You will meet me at the northernmost edge of the Ogier grove one hour before sunset with your horses and whatever you will need for the journey. Tell no one of this.”

“We are not supposed to leave the Tower grounds without permission,” Nynaeve said slowly.

“You have my permission. Tell no one. No one at all. The Black Ajah walks the halls of the White Tower.”

Egwene gasped, and heard an echoed gasp from Nynaeve, but Nynaeve recovered quickly. “I thought all Aes Sedai denied the existence of—of that.”

Liandrin’s mouth tightened into a sneer. “Many do, but Tarmon Gai’don approaches, and the time leaves when denials can be made. The Black Ajah, it is the opposite of everything for which the Tower stands, but it exists, child. It is everywhere, any woman could belong to it, and it serv

es the Dark One. If your friends are pursued by the Shadow, do you think the Black Ajah will leave you alive and free to help them? Tell no one—no one!—or you may not live to reach Toman Head. One hour before sunset. Do not fail me.” With that, she was gone, the door closing firmly behind her.

Egwene collapsed onto her bed with her hands on her knees. “Nynaeve, she’s Red Ajah. She can’t know about Rand. If she did. . . .”

“She cannot know,” Nynaeve agreed. “I wish I knew why a Red wanted to help. Or why she’s willing to work with Moiraine. I’d have sworn neither of them would give the other water if she were dying of thirst.”

“You think she’s lying?”

“She is Aes Sedai,” Nynaeve said dryly. “I’ll wager my best silver pin against a blueberry that every word she said was true. But I wonder if we heard what we thought we did.”

“The Black Ajah.” Egwene shivered. “There was no mistaking what she said about that, the Light help us.”

“No mistaking,” Nynaeve said. “And she’s forestalled us asking anyone for advice, because after that, who can we trust? The Light help us indeed.”

Min and Elayne came bustling in, slamming the door behind them. “Are you really going?” Min asked, and Elayne gestured toward the tiny hole in the wall above Egwene’s bed, saying, “We listened from my room. We heard everything.”

Egwene exchanged glances with Nynaeve, wondering how much they had overheard, and saw the same concern on Nynaeve’s face. If they manage to cipher out about Rand. . . .

“You have to keep this to yourselves,” Nynaeve cautioned them. “I suppose Liandrin has arranged permission from Sheriam for us to go, but even if she hasn’t, even if they start searching the Tower from top to bottom for us tomorrow, you mustn’t say a word.”

“Keep it to myself?” Min said. “No fear on that. I’m going with you. All I do all day is try to explain to one Brown sister or another something I don’t understand myself. I can’t even go for a walk without the Amyrlin herself popping out and asking me to read whoever we see. When that woman asks you to do something, there doesn’t seem to be any way out of it. I must have read half the White Tower for her, but she always wants another demonstration. All I needed was an excuse to leave, and this is it.” Her face wore a look of determination that allowed no argument.

Conan the Unconquered

Conan the Unconquered Conan the Triumphant

Conan the Triumphant The Eye of the World

The Eye of the World The Great Hunt

The Great Hunt Conan the Victorious

Conan the Victorious The Dragon Reborn

The Dragon Reborn The Fires of Heaven

The Fires of Heaven Winter's Heart

Winter's Heart Lord of Chaos

Lord of Chaos The Shadow Rising

The Shadow Rising Conan the Defender

Conan the Defender The Strike at Shayol Ghul

The Strike at Shayol Ghul The Path of Daggers

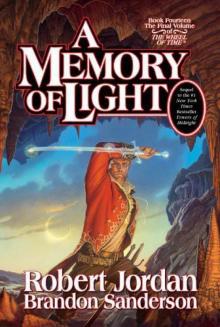

The Path of Daggers A Memory of Light

A Memory of Light Knife of Dreams

Knife of Dreams Crossroads of Twilight

Crossroads of Twilight Conan the Invincible

Conan the Invincible The Gathering Storm

The Gathering Storm Warrior of the Altaii

Warrior of the Altaii A Crown of Swords

A Crown of Swords The Wheel of Time

The Wheel of Time Towers of Midnight

Towers of Midnight Conan Chronicles 2

Conan Chronicles 2 Conan the Magnificent

Conan the Magnificent New Spring

New Spring What the Storm Means

What the Storm Means A Memory of Light twot-14

A Memory of Light twot-14 New Spring: The Novel

New Spring: The Novel Towers of midnight wot-13

Towers of midnight wot-13 A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14

A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14 A Crown of Swords twot-7

A Crown of Swords twot-7 Lord of Chaos twot-6

Lord of Chaos twot-6 The Great Hunt twot-2

The Great Hunt twot-2 The Shadow Rising twot-4

The Shadow Rising twot-4![Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/03/wheel_of_time-11_knife_of_dreams_preview.jpg) Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams

Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams The Dragon Reborn twot-3

The Dragon Reborn twot-3 The Wheel of Time Companion

The Wheel of Time Companion The Fires of Heaven twot-5

The Fires of Heaven twot-5 Prologue to Towers of Midnight

Prologue to Towers of Midnight The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8

The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8 The Path of Daggers twot-8

The Path of Daggers twot-8 By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light

By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light Crossroads of Twilight twot-10

Crossroads of Twilight twot-10 The Gathering Storm twot-12

The Gathering Storm twot-12 Winter's Heart twot-9

Winter's Heart twot-9 Knife of Dreams twot-11

Knife of Dreams twot-11 New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)

New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)