- Home

- Robert Jordan

The Great Hunt Page 69

The Great Hunt Read online

Page 69

Min hesitated only long enough for one anguished look at Egwene before leaving. Nothing Min could say or do would do anything except make matters worse, but Egwene could not help looking longingly at the door as it closed behind her friend.

Renna took the chair, frowning at Egwene. “I must punish you severely for this. We will both be called to the Court of the Nine Moons—you for what you can do; I as your sul’dam and trainer—and I will not allow you to disgrace me in the eyes of the Empress. I will stop when you tell me how much you love being damane and how obedient you will be after this. And, Tuli. Make me believe every word.”

CHAPTER

43

A Plan

Outside in the low-ceilinged hallway, Min dug her nails into her palms at the first piercing cry from the room. She took a step toward the door before she could stop herself, and when she did stop, tears sprang up in her eyes. Light help me, all I can do is make it worse. Egwene, I’m sorry. I’m sorry.

Feeling worse than useless, she picked up her skirts and ran, and Egwene’s screams pursued her. She could not make herself stay, and leaving made her feel a coward. Half blind with weeping, she found herself in the street before she knew it. She had intended to go back to her room, but now she could not do it. She could not stand the thought that Egwene was being hurt while she sat warm and safe under the next roof. Scrubbing the tears from her eyes, she swept her cloak around her shoulders and started down the street. Every time she cleared her eyes, new tears began trickling along her cheeks. She was not accustomed to weeping openly, but then she was not accustomed to feeling so helpless, so useless. She did not know where she was going, only that it had to be as far as she could reach from Egwene’s cries.

“Min!”

The low-pitched shout brought her up short. At first, she could not make out who had called. Relatively few people walked the street this close to where the damane were housed. Aside from a lone man trying to interest two Seanchan soldiers in buying the picture he would draw of them with his colored chalks, everyone local tried to step along quickly without actually appearing to run. A pair of sul’dam strolled by, damane trailing behind with eyes down; the Seanchan women were talking about how many more marath’damane they expected to find before they sailed. Min’s eyes passed right over the two women in long fleece coats, then swung back in wonder as they came toward her. “Nynaeve? Elayne?”

“None other.” Nynaeve’s smile was strained; both women had tight eyes, as if they fought worried frowns. Min thought she had never seen anything as wonderful as the sight of them. “That color becomes you,” Nynaeve continued. “You should have taken up dresses long since. Though I’ve thought of breeches myself since I saw them on you.” Her voice sharpened as she drew close enough to see Min’s face. “What is the matter?”

“You’ve been crying,” Elayne said. “Has something happened to Egwene?”

Min gave a start and looked back over her shoulder. A sul’dam and damane came down the steps she had used and turned the other way, toward the stables and horse yards. Another woman with the lightning panels on her dress stood at the top of the stairs talking with someone still inside. Min grabbed her friends by the arms and hurried them down the street toward the harbor. “It’s dangerous for you two here. Light, it’s dangerous for you to be in Falme. There are damane everywhere, and if they find you. . . . You do know what damane are? Oh, you don’t know how good it is to see you both.”

“I imagine about as half as good as it is to see you,” Nynaeve said. “Do you know where Egwene is? Is she in one of those buildings? Is she all right?”

Min hesitated a fraction before saying, “She’s as well as can be expected.” Min could see it all too well, if she told them what was happening to Egwene right that moment. Nynaeve was as likely as not to go storming back in an attempt to stop it. Light, let it be over by now. Light, make her bend her stubborn neck just once before they almost break it first. “I don’t know how to get her out, though. I found a ship captain who I think will take us if we can reach his ship with her—he won’t help unless we make it that far, and I cannot say I blame him—but I have no idea how to do even that much.”

“A ship,” Nynaeve said thoughtfully. “I had meant to simply ride east, but I must say I’ve worried about it. As nearly as I can make out, we would have to be almost off Toman Head before we were clear of Seanchan patrols completely, and then there’s supposed to be fighting of some sort on Almoth Plain. I never thought of a ship. We have horses, and we do not have money for passage. How much does this man want?”

Min shrugged. “I never got that far. We don’t have any money, either. I thought I could put off paying until after we sail. Afterwards . . . well, I don’t think he’ll put into any port where there are Seanchan. Wherever he threw us off, it would have to be better than here. The problem is convincing him to sail at all. He wants to, but they patrol off the harbor, too, and there is no way of telling if there’s a damane on one of their ships until it’s too late. ‘Give me a damane of my own on my deck,’ he says, ‘and I will sail this instant.’ Then he starts talking about drafts and shoals and lee shores. I don’t understand any of that, but as long as I smile and nod every now and then, he keeps talking, and I think if I can keep him talking long enough, he’ll talk himself into sailing.” She drew a shuddering breath; her eyes started stinging again. “Only, I don’t think there’s time to let him talk himself into it anymore. Nynaeve, they’re going to send Egwene back to Seanchan, and soon.”

Elayne gasped. “But, why?”

“She is able to find ore,” Min said miserably. “A few days, she says, and I don’t know if a few days is enough for this man to convince himself to sail. Even if it is, how do we take that Shadow-spawned collar off her? How do we get her out of the house?”

“I wish Rand were here.” Elayne sighed, and when they both looked at her, she blushed and quickly added, “Well, he does have a sword. I wish we had somebody with a sword. Ten of them. A hundred.”

“It isn’t swords or brawn we need now,” Nynaeve said, “but brains. Men usually think with the hair on their chests.” She touched her chest absently, as if feeling something through her coat. “Most of them do.”

“We would need an army,” Min said. “A large army. The Seanchan were outnumbered when they faced the Taraboners, and the Domani, and they won every battle easily, from what I hear.” She hurriedly pulled Nynaeve and Elayne to the opposite side of the street as a damane and sul’dam climbed past them on the other side. She was relieved there was no need for urging; the other two watched the linked women go as warily as she. “Since we don’t have an army, the three of us will have to do it. I hope one of you can think of something I haven’t; I’ve wracked my brains, and I always stumble when it comes to the a’dam, the leash and collar. Sul’dam don’t like anyone watching too closely when they open them. I think I can get you inside, if that will help. One of you, anyway. They think of me as a servant, but servants may have visitors, as long as they keep to the servants’ quarters.”

Nynaeve wore a thoughtful frown, but her face cleared almost immediately, taking on a purposeful look. “Don’t you worry, Min. I have a few ideas. I have not spent my time here idly. You take me to this man. If he is any harder to handle than the Village Council with their backs up, I will eat this coat.”

Elayne nodded, grinning, and Min felt the first real hope she had had since arriving in Falme. For an instant Min found herself reading the auras of the other two women. There was danger, but that was to be expected—and new things, too, among the images she had seen before; it was like that, sometimes. A man’s ring of heavy gold floated above Nynaeve’s head, and above Elayne’s, a red-hot iron and an axe. They meant trouble, she was sure, but it seemed distant, somewhere in the future. Only for a moment did the reading last, and then all she saw was Elayne and Nynaeve, watching her expectantly.

“It’s down near the harbor,” she said.

The sloping street became

more crowded the further down they went. Street peddlers rubbed elbows with merchants who had brought wagons in from the inland villages and would not go out again until winter had come and gone, hawkers with their trays called to the passersby, Falmen in embroidered cloaks brushed past farm families in heavy fleece coats. Many people had fled here from villages further from the coast. Min saw no point to it—they had leaped from the possibility of a visit from the Seanchan to the certainty of Seanchan all around them—but she had heard what the Seanchan did when they first came to a village, and she could not blame the villagers too much for fearing another appearance. Everyone bowed when Seanchan walked past or a curtained palanquin was carried by up the steep street.

Min was glad to see Nynaeve and Elayne knew about the bowing. Bare-chested bearers paid no more mind to the people who bent themselves than did arrogant, armored soldiers, but failure to bow would surely catch their eyes.

They talked a little as they moved down the street, and she was surprised at first to learn they had been in the town only a few days less than Egwene and herself. After a moment, though, she decided it was no wonder they had not met earlier, not with the crowds in the streets. She had been reluctant to spend time further from Egwene than was necessary; there was always the fear that she would go for her allowed visit and find Egwene gone. And now she will be. Unless Nynaeve can think of something.

The smell of salt and pitch grew heavy in the air, and gulls cried, wheeling overhead. Sailors appeared in the throng, many still barefoot despite the cold.

The inn had been hastily renamed The Three Plum Blossoms, but part of the word “Watcher” still showed through the slapdash paint work on the sign. Despite the crowds outside, the common room was little more than half full; prices were too high for many people to afford time sitting over ale. Roaring fires on hearths at either end of the room warmed it, and the fat innkeeper was in his shirtsleeves. He eyed the three women, frowning, and Min thought it was her Seanchan dress that stopped him from telling them to leave. Nynaeve and Elayne, in their farm women’s coats, certainly did not look as if they had money to spend.

The man she was looking for was alone at a table in a corner, in his accustomed place, muttering into his wine. “Do you have time to talk, Captain Domon?” she said.

He looked up, brushing a hand across his beard when he saw she was not alone. She still thought his bare upper lip looked odd with the beard. “So you do bring friends to drink up my coin, do you? Well, that Seanchan lord bought my cargo, so coin I have. Sit.” Elayne jumped as he suddenly bellowed, “Innkeeper! Mulled wine here!”

“It’s all right,” Min told her, taking a place on the end of one of the benches at the table. “He only looks and sounds like a bear.” Elayne sat down on the other end, looking doubtful.

“A bear, do I be?” Domon laughed. “Maybe I do. But what of you, girl? Have you given over thought of leaving? That dress do look Seanchan to me.”

“Never!” Min said fiercely, but the appearance of a serving girl with the steaming, spiced wine made her fall silent.

Domon was just as wary. He waited until the girl had gone with his coins before saying, “Fortune prick me, girl, I mean no offense. Most people only want to go on with their lives, whether their lords be Seanchan or any other.”

Nynaeve leaned her forearms on the table. “We also want to go on with our lives, Captain, but without any Seanchan. I understand you intend to sail soon.”

“I would sail today, if I could,” Domon said glumly. “Every two or three days that Turak do send for me to tell him tales of the old things I have seen. Do I look a gleeman to you? I did think I could spin a tale or two and be on my way, but now I think when I no entertain him any longer, it be an even wager whether he do let me go or have my head cut off. The man do look soft, but he be as hard as iron, and as coldhearted.”

“Can your ship avoid the Seanchan?” Nynaeve asked.

“Fortune prick me, could I make it out of the harbor without a damane rips Spray to splinters, I can. If I do no let a Seanchan ship with a damane come too close once I do make the sea. There be shoal waters all along this coast, and Spray do have a shallow draft. I can take her into waters those lumbering Seanchan hulks can no risk. They must be wary of the winds close inshore this time of year, and once I do have Spray—”

Nynaeve cut him off. “Then we will take passage with you, Captain. There will be four of us, and I will expect you to be ready to sail as soon as we are aboard.”

Domon scrubbed a finger across his upper lip and peered into his wine. “Well, as to that, there still do be the matter of getting out of the harbor, you see. These damane—”

“What if I tell you you will sail with something better than damane?” Nynaeve said softly. Min’s eyes widened as she realized what Nynaeve intended.

Almost under her breath, Elayne murmured, “And you tell me to be careful.”

Domon had eyes only for Nynaeve, and they were wary eyes. “What do you mean?” he whispered.

Nynaeve opened her coat to fumble at the back of her neck, finally pulling out a leather cord that had been tucked inside her dress. Two gold rings hung on the cord. Min gasped when she saw one—it was the heavy man’s ring she had seen when she read Nynaeve in the street—but she knew it was the other, slighter and made for a woman’s slender finger, that made Domon’s eyes bulge. A serpent biting its own tail.

“You know what this means,” Nynaeve said, starting to slip the Serpent ring from the cord, but Domon closed his hand over it.

“Put it away.” His eyes darted uneasily; no one was looking at them that Min could see, but he looked as if he thought everyone was staring. “That ring do be dangerous. If it be seen. . . .”

“As long as you know what it means,” Nynaeve said with a calm that made Min envious. She pulled the cord from Domon’s hand and retied it around her neck.

“I know,” he said hoarsely. “I do know what it means. Maybe there do be a chance if you. . . . Four, you say? This girl who do like to listen to my tongue wag, she do be one of the four, I take it. And you, and. . . .” He frowned at Elayne. “Surely this child is no—no one like you.”

Elayne straightened angrily, but Nynaeve put a hand on her arm and smiled soothingly at Domon. “She travels with me, Captain. You might be surprised by what we can do even before we earn the right to a ring. When we sail, you will have three on your ship who can fight damane if need be.”

“Three,” he breathed. “There do be a chance. Maybe. . . .” His face brightened for a moment, but as he looked at them, it grew serious again. “I should take you to Spray right now and cast off, but Fortune prick me if I can no tell you what you face here if you stay, and maybe even if you go with me. Listen to me, and mark what I do say.” He took another cautious look around, and still lowered his voice and chose his words carefully. “I did see a—a woman who wore a ring like that taken by the Seanchan. A pretty, slender little woman she was, with a big War—a big man with her who did look as if he did know how to use his sword. One of them must have been careless, for the Seanchan did have an ambush laid for them. The big man put six, seven soldiers on the ground before he did die himself. The—the woman. . . . Six damane they did put around her, stepping out of the alleys of a sudden. I did think she would . . . do something—you know what I mean—but. . . . I know nothing of these things. One moment she did look as if she would destroy them all, then a look of horror did come on her face, and she did scream.”

“They cut her off from the True Source.” Elayne’s face was white.

“No matter,” Nynaeve said calmly. “We will not allow the same to be done to us.”

“Aye, mayhap it will be as you say. But I will remember it until I die. Ryma, help me. That is what she did scream. And one of the damane did fall down crying, and they did put one of those collars on the neck of the . . . woman, and I . . . I did run.” He shrugged, and rubbed his nose, and peered into his wine. “I have seen three women taken, and I have no s

tomach for it. I would leave my aged grandmother standing on the dock to sail from here, but I did have to tell you.”

“Egwene said they have two prisoners,” Min said slowly. “Ryma, a Yellow, and she didn’t know who the other is.” Nynaeve gave her a sharp look, and she fell silent, blushing. From the look on Domon’s face, it had not furthered their cause any to tell him the Seanchan held two Aes Sedai, not just one.

Yet abruptly he stared at Nynaeve and took a long gulp of wine. “Do that be why you are here? To free . . . those two? You did say there would be three of you.”

“You know what you need to know,” Nynaeve told him briskly. “You must be ready to sail on the instant anytime in the next two or three days. Will you do it, or will you remain here to see if they will cut off your head after all? There are other ships, Captain, and I mean to have passage assured on one of them today.”

Min held her breath; under the table, her fingers were knotted.

Finally, Domon nodded. “I will be ready.”

When they returned to the street, Min was surprised to see Nynaeve sag against the front of the inn as soon as the door closed. “Are you ill, Nynaeve?” she asked anxiously.

Nynaeve drew a long breath and stood up straight, tugging at her coat. “With some people,” she said, “you have to be certain. If you show them one glimmer of doubt, they’ll sweep you off in some direction you don’t want to go. Light, but I was afraid he was going to say no. Come, we have plans yet to make. There are still one or two small problems to work out.”

“I hope you don’t mind fish, Min,” Elayne said.

One or two small problems? Min thought as she followed them. She hoped very much that Nynaeve was not just being certain again.

Conan the Unconquered

Conan the Unconquered Conan the Triumphant

Conan the Triumphant The Eye of the World

The Eye of the World The Great Hunt

The Great Hunt Conan the Victorious

Conan the Victorious The Dragon Reborn

The Dragon Reborn The Fires of Heaven

The Fires of Heaven Winter's Heart

Winter's Heart Lord of Chaos

Lord of Chaos The Shadow Rising

The Shadow Rising Conan the Defender

Conan the Defender The Strike at Shayol Ghul

The Strike at Shayol Ghul The Path of Daggers

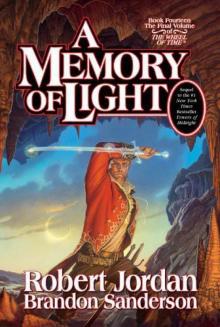

The Path of Daggers A Memory of Light

A Memory of Light Knife of Dreams

Knife of Dreams Crossroads of Twilight

Crossroads of Twilight Conan the Invincible

Conan the Invincible The Gathering Storm

The Gathering Storm Warrior of the Altaii

Warrior of the Altaii A Crown of Swords

A Crown of Swords The Wheel of Time

The Wheel of Time Towers of Midnight

Towers of Midnight Conan Chronicles 2

Conan Chronicles 2 Conan the Magnificent

Conan the Magnificent New Spring

New Spring What the Storm Means

What the Storm Means A Memory of Light twot-14

A Memory of Light twot-14 New Spring: The Novel

New Spring: The Novel Towers of midnight wot-13

Towers of midnight wot-13 A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14

A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14 A Crown of Swords twot-7

A Crown of Swords twot-7 Lord of Chaos twot-6

Lord of Chaos twot-6 The Great Hunt twot-2

The Great Hunt twot-2 The Shadow Rising twot-4

The Shadow Rising twot-4![Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/03/wheel_of_time-11_knife_of_dreams_preview.jpg) Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams

Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams The Dragon Reborn twot-3

The Dragon Reborn twot-3 The Wheel of Time Companion

The Wheel of Time Companion The Fires of Heaven twot-5

The Fires of Heaven twot-5 Prologue to Towers of Midnight

Prologue to Towers of Midnight The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8

The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8 The Path of Daggers twot-8

The Path of Daggers twot-8 By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light

By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light Crossroads of Twilight twot-10

Crossroads of Twilight twot-10 The Gathering Storm twot-12

The Gathering Storm twot-12 Winter's Heart twot-9

Winter's Heart twot-9 Knife of Dreams twot-11

Knife of Dreams twot-11 New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)

New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)