- Home

- Robert Jordan

The Fires of Heaven Page 9

The Fires of Heaven Read online

Page 9

It struck Rand suddenly that this was the real reason that some Aiel took what he had revealed so hard. To those, it must seem that their ancestors had sworn gai’shain, not only for themselves but for all succeeding generations. And those generations—all, down to the present day—had broken ji’e’toh by taking up the spear. Had the men in front of him ever worried along those lines? Ji’e’toh was very serious business to an Aiel.

The gai’shain departed on soft slippered feet, barely making a sound. None of the clan chiefs touched their wine, or the food.

“Is there any hope that Couladin will meet with me?” Rand knew there was not; he had stopped sending requests for a meeting once he learned Couladin was having the messengers skinned alive. But it was a way to start the others talking.

Han snorted. “The only word we have had from him is that he means to flay you when next he sees you. Does that sound as if he will talk?”

“Can I break the Shaido away from him?”

“They follow him,” Rhuarc said. “He is not a chief at all, but they believe he is.” Couladin had never entered those glass columns; he might even still believe as he claimed, that everything Rand had said was a lie. “He says that he is the Car’a’carn, and they believe that as well. The Shaido Maidens who came, came for their society, and that because Far Dareis Mai carried your honor. None else will.”

“We send scouts to watch them,” Bruan said, “and the Shaido kill them when they can—Couladin builds the makings of half a dozen feuds—but so far he shows no signs of attacking us here. I have heard that he claims we have defiled Rhuidean, and that attacking us here would only deepen the desecration.”

Erim grunted and shifted on his cushion. “He means there are enough spears here to kill every Shaido twice over and to spare.” He popped a piece of white cheese into his mouth, growling around it. “The Shaido were ever cowards and thieves.”

“Honorless dogs,” Bael and Jheran said together, then stared at one another as though each thought the other had tricked him into something.

“Honorless or not,” Bruan said quietly, “Couladin’s numbers are growing.” Calm as he sounded, he still took a deep drink from his goblet before going on. “You all know what I am speaking of. Some of those who run, after the bleakness, do not throw away their spears. Instead they join with their societies among the Shaido.”

“No Tomanelle has ever broken clan,” Han barked.

Bruan looked past Rhuarc and Erim at the Tomanelle chief and said deliberately, “It has happened in every clan.” Without waiting for another challenge to his word, he settled back on his cushion. “It cannot be called breaking clan. They join their societies. Like the Shaido Maidens who have come to their Roof here.”

There were a few mutters, but no one disputed him this time. The rules governing Aiel warrior societies were complex, and in some ways their members felt as closely bound to society as to clan. For instance, members of the same society would not fight each other even if their clans were in blood feud. Some men would not marry a woman too closely related to a member of their own society, just as if that made her their own close blood kin. The ways of Far Dareis Mai, the Maidens of the Spear, Rand did not even want to think about.

“I need to know what Couladin intends,” he told them. Couladin was a bull with a bee in his ear; he might charge in any direction. Rand hesitated. “Would it violate honor to send people to join their societies among the Shaido?” He did not need to describe what he meant any further. To a man, they stiffened where they lay, even Rhuarc, eyes cold enough to banish the heat from the room.

“To spy in that manner”—Erim twisted his mouth around “spy” as if the word tasted foul—“would be like spying on your own sept. No one of honor would do such a thing.”

Rand refrained from asking whether they might find someone with a slightly less prickly honor. The Aiel sense of humor was a strange thing, often cruel, but about some matters they had none at all.

To change the subject, he asked, “Is there any word from across the Dragonwall?” He knew the answer; that sort of news spread quickly even among as many Aiel as were gathered around Rhuidean.

“None worth the telling,” Rhuarc replied. “With the troubles among the treekillers, few peddlers come into the Three-fold Land.” That was the Aiel name for the Waste; a punishment for their sin, a testing ground for their courage, an anvil to shape them. “Treekillers” was what they called Cairhienin. “The Dragon banner still flies over the Stone of Tear. Tairens have moved north into Cairhien as you ordered, to distribute food among the treekillers. Nothing more.”

“You should have let the treekillers starve,” Bael muttered, and Jheran closed his mouth with a snap. Rand suspected he had been about to say much the same.

“Treekillers are fit for nothing except to be killed or sold as animals in Shara,” Erim said grimly. Those were two of the things Aiel did to those who came into the Waste uninvited; only gleeman, peddlers, and Tinkers had safe passage, though Aiel avoided the Tinkers as if they carried fever. Shara was the name of the lands beyond the Waste; not even the Aiel knew much about them.

From the corner of his eye, Rand saw two women standing expectantly just inside the tall, arched doorway. Someone had hung strings of colored beads there, red and blue, to replace the missing doors. One of the women was Moiraine. For a moment he considered making them wait; Moiraine had that irritatingly commanding look on her face, clearly expecting them to break off everything for her. Only, there was really nothing left to discuss, and he could tell from the men’s eyes that they did not want to make conversation. Not so soon after speaking of the bleakness, and the Shaido.

Sighing, he stood, and the clan chiefs imitated him. All except Han were as tall as he or taller. Where Rand had grown up, Han would have been considered of average height or better; among Aiel, he was accounted short. “You know what must be done. Bring in the rest of the clans, and keep an eye on the Shaido.” He paused a moment, then added, “It will end well. As well for the Aiel as I can manage.”

“The prophecy said you would break us,” Han said sourly, “and you have made a good beginning. But we will follow you. Till shade is gone,” he recited, “till water is gone, into the Shadow with teeth bared, screaming defiance with the last breath, to spit in Sightblinder’s eye on the Last Day.” Sightblinder was one of the Aiel names for the Dark One.

There was nothing for Rand except to make the proper response. Once he had not known it. “By my honor and the Light, my life will be a dagger for Sightblinder’s heart.”

“Until the Last Day,” the Aiel finished, “to Shayol Ghul itself.” The harper played on pacifically.

The chiefs filed out past the two women, eyeing Moiraine respectfully. There was nothing of fear in them. Rand wished he could be as sure of himself. Moiraine had too many plans for him, too many ways of pulling strings he did not know she had tied to him.

The two women came in as soon as the chiefs were gone, Moiraine as cool and elegant as ever. A small, pretty woman, with or without those Aes Sedai features he could never put an age to, she had abandoned the damp, cooling cloth for her temples. In its place, a small blue stone hung suspended on her forehead from a fine golden chain in her dark hair. It would not have mattered if she had kept it; nothing could diminish her queenly carriage. She usually seemed to own a foot more height than she actually had, and her eyes were all confidence and command.

The other woman was taller, though still short of his shoulder, and young, not ageless. Egwene, whom he had grown up with. Now, except for her big dark eyes, she could almost have passed as an Aiel woman, and not only for her tanned face and hands. She wore a full Aiel skirt of brown wool and a loose white blouse of a plant fiber called algode. Algode was softer than even the finest-woven wool; it would do very well for trade, if he ever convinced the Aiel. A gray shawl hung around Egwene’s shoulders, and a folded gray scarf made a wide band to hold back the dark hair that fell below her shoulders. Unlike m

ost Aielwomen, she wore only one bracelet, ivory carved into a circle of flames, and a single necklace of gold and ivory beads. And one more thing. A Great Serpent ring on her left hand.

Egwene had been studying with some of the Aiel Wise Ones—exactly what, Rand did not know, though he more than suspected something to do with dreams; Egwene and the Aielwomen were closemouthed—but she had studied in the White Tower, too. She was one of the Accepted, on the way to becoming Aes Sedai. And passing herself off, here and in Tear at least, as full Aes Sedai already. Sometimes he teased her about that; she did not take his japes very well, though.

“The wagons will be ready to leave for Tar Valon soon,” Moiraine said. Her voice was musical, crystalline.

“Send a strong guard,” Rand said, “or Kadere may not take them where you want.” He turned for the windows again, wanting to look out and think, about Kadere. “You’ve not needed me to hold your hand or give you permission before.”

Abruptly something seemed to strike him across the shoulders, for all the world like a thick hickory stick; only the slight feel of goose bumps on his skin, not likely in this heat, told him that one of the women had channeled.

Spinning back to face them, he reached out to saidin, filled himself with the One Power. The Power felt like life itself swelling inside him, as if he were ten times, a hundred times as alive; the Dark One’s taint filled him, too, death and corruption, like maggots crawling in his mouth. It was a torrent that threatened to sweep him away, a raging flood he had to fight every moment. He was almost used to it now, and at the same time he would never be used to it. He wanted to hold on to the sweetness of saidin forever, and he wanted to vomit. And all the while the deluge tried to scour him to the bone and burn his bones to ash.

The taint would drive him mad eventually, if the Power did not kill him first; it was a race between the two. Madness had been the fate of every man who had channeled since the Breaking of the World began, since that day when Lews Therin Telamon, the Dragon, and his Hundred Companions had sealed up the Dark One’s prison at Shayol Ghul. The last backblast from that sealing had tainted the male half of the True Source, and men who could channel, madmen who could channel, had torn the world apart.

He filled himself with the Power. . . . And he could not tell which woman had done it. They both looked at him as if butter would not melt in their mouths, each with an eyebrow arched almost identically in slightly amused questioning. Either or both could be embracing the female half of the Source right that instant, and he would never know.

Of course, a stick across the shoulders was not Moiraine’s way; she found other means of chastising, more subtle, usually more painful in the end. Yet even sure that it must have been Egwene, he did nothing. Proof. Thought slid along the outside of the Void; he floated within, in emptiness, thought and emotion, even his anger, distant. I will do nothing without proof. I will not be goaded, this time. She was not the Egwene he had grown up with; she had become part of the Tower since Moiraine sent her there. Moiraine again. Always Moiraine. Sometimes he wished he were rid of Moiraine. Only sometimes?

He concentrated on her. “What do you want of me?” His voice sounded flat and cold to his own ears. The Power stormed inside him. Egwene had told him that for a woman, touching saidar, the female half of the Source, was an embrace; for a man, always, it was a war without mercy. “And don’t mention wagons again, little sister. I usually find out what you mean to do long after it is done.”

The Aes Sedai frowned at him, and no wonder. She was surely not used to being addressed so, not by any man, even the Dragon Reborn. He had no idea himself where “little sister” had come from; sometimes of late words seemed to pop into his head. A touch of madness, perhaps. Some nights he lay awake till the small hours, worrying about that. Inside the Void, it seemed someone else’s worry.

“We should speak alone.” She gave the harper a cool glance.

Jasin Natael, as he called himself here, lay half-sprawled on cushions against one of the windowless walls, softly playing the harp perched on his knee, its upper arm carved and gilded to resemble the creatures on Rand’s forearms. Dragons, the Aiel called them. Rand had only suspicions where Natael had gotten the thing. He was a dark-haired man, who would have been accounted taller than most elsewhere than the Aiel Waste, in his middle years. His coat and breeches were dark blue silk suitable for a royal court, elaborately embroidered with thread-of-gold on collar and cuffs, everything buttoned up or laced despite the heat. The fine clothes were at odds with his gleeman’s cloak spread out beside him. A perfectly sound cloak, but covered completely with hundreds of patches in nearly as many colors, all sewn so as to flutter at the slightest breeze, it signified a country entertainer, a juggler and tumbler, musician and storyteller who wandered from village to village. Certainly not a man to wear silk. The man had his conceits. He appeared completely immersed in his music.

“You can say what you wish in front of Natael,” Rand said. “He is gleeman to the Dragon Reborn, after all.” If keeping the matter secret was important enough, she would press it, and he would send Natael away, though he did not like the man to be out of his sight.

Egwene sniffed loudly and shifted her shawl on her shoulders. “Your head is swelled up like an overripe melon, Rand al’Thor.” She said it flatly, as a statement of fact.

Anger bubbled outside the Void. Not at what she had said; she had been in the habit of trying to take him down a rung even when they were children, usually whether he deserved it or not. But of late it seemed to him she had taken to working with Moiraine, trying to put him off balance so the Aes Sedai could push him where she wanted. When they were younger, before they learned what he was, he and Egwene had thought they would marry one day. And now she sided with Moiraine against him.

Face hard, he spoke more roughly than he intended. “Tell me what you want, Moiraine. Tell me here and now, or let it wait until I can find time for you. I’m very busy.” That was an outright lie. Most of his time was spent practicing the sword with Lan, or the spears with Rhuarc, or learning to fight with hands and feet from both. But if there was any bullying to be done here today, he would do it. Natael could hear anything. Almost anything. So long as Rand knew where he was at all times.

Moiraine and Egwene both frowned, but the real Aes Sedai at least seemed to see he would not be budged this time. She glanced at Natael, her mouth tightening—the man still seemed deep in his music—then took a thick wad of gray silk from her pouch.

Unfolding it, she laid what it had contained on the table, a disc the size of a man’s hand, half dead black, half purest white, the two colors meeting in a sinuous line to form two joined teardrops. That had been the symbol of Aes Sedai, before the Breaking, but this disc was more. Only seven like it had ever been made, the seals on the Dark One’s prison. Or rather, each was a focus for one of those seals. Drawing her belt knife, its hilt wrapped in silver wire, Moiraine scraped delicately at the edge of the disc. And a tiny flake of solid black fell away.

Even encased in the Void, Rand gasped. The emptiness itself quivered, and for an instant the Power threatened to overwhelm him. “Is this a copy? A fake?”

“I found this in the square below,” Moiraine said. “It is real, though. The one I brought with me from Tear is the same.” She could have been saying she wanted pea soup for the midday meal. Egwene, on the other hand, clutched her shawl around her as if cold.

Rand felt the stirrings of fright himself, oozing across the surface of the Void. It was an effort to let go of saidin, but he forced himself. If he lost concentration, the Power could destroy him where he stood, and he wanted all his attention on the matter at hand. Even so, even with the taint, it was a loss.

That flake lying on the table was impossible. Those discs were made of cuendillar, heartstone, and nothing made of cuendillar could be broken, not even by the One Power. Whatever force was used against it only made it stronger. The making of heartstone had been lost in the Breaking of the World, but whatev

er had been made of it during the Age of Legends still existed, even the most fragile vase, even if the Breaking had sunk it to the bottom of the ocean or buried it beneath a mountain. Of course, three of the seven discs were broken already, but it had taken a good deal more than a knife.

Come to think of it, though, he did not know how those three really had been broken. If no force short of the Creator could break heartstone, then that should be that.

“How?” he asked, surprised that his voice was still as steady as when the Void had surrounded him.

“I do not know,” Moiraine replied, just as calm outwardly. “But you do see the problem? A fall from the table could break this. If the others, wherever they may be, are like this, four men with hammers could break open that hole in the Dark One’s prison again. Who can even say how effective one is, in this condition?”

Rand saw. I’m not ready yet. He was not sure he ever would be ready, but he surely was not yet. Egwene looked as though she were staring into her own open grave.

Rewrapping the disc, Moiraine replaced it in her pouch. “Perhaps I will think of a possibility before I carry this to Tar Valon. If we know why, perhaps something can be done about it.”

He was caught by the image of the Dark One reaching out from Shayol Ghul once more, eventually breaking free completely; fires and darkness covered the world in his mind, flames that consumed and gave no light, blackness solid as stone squeezing the air. With that filling his head, what Moiraine had just said took a moment to penetrate. “You intend to go yourself?” He had thought she meant to stick to him like moss to a rock. Isn’t this what you want?

Conan the Unconquered

Conan the Unconquered Conan the Triumphant

Conan the Triumphant The Eye of the World

The Eye of the World The Great Hunt

The Great Hunt Conan the Victorious

Conan the Victorious The Dragon Reborn

The Dragon Reborn The Fires of Heaven

The Fires of Heaven Winter's Heart

Winter's Heart Lord of Chaos

Lord of Chaos The Shadow Rising

The Shadow Rising Conan the Defender

Conan the Defender The Strike at Shayol Ghul

The Strike at Shayol Ghul The Path of Daggers

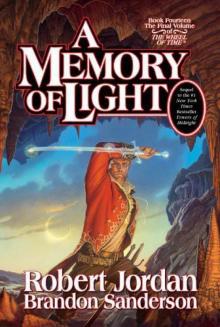

The Path of Daggers A Memory of Light

A Memory of Light Knife of Dreams

Knife of Dreams Crossroads of Twilight

Crossroads of Twilight Conan the Invincible

Conan the Invincible The Gathering Storm

The Gathering Storm Warrior of the Altaii

Warrior of the Altaii A Crown of Swords

A Crown of Swords The Wheel of Time

The Wheel of Time Towers of Midnight

Towers of Midnight Conan Chronicles 2

Conan Chronicles 2 Conan the Magnificent

Conan the Magnificent New Spring

New Spring What the Storm Means

What the Storm Means A Memory of Light twot-14

A Memory of Light twot-14 New Spring: The Novel

New Spring: The Novel Towers of midnight wot-13

Towers of midnight wot-13 A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14

A Memory Of Light: Wheel of Time Book 14 A Crown of Swords twot-7

A Crown of Swords twot-7 Lord of Chaos twot-6

Lord of Chaos twot-6 The Great Hunt twot-2

The Great Hunt twot-2 The Shadow Rising twot-4

The Shadow Rising twot-4![Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/03/wheel_of_time-11_knife_of_dreams_preview.jpg) Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams

Wheel of Time-11] Knife of Dreams The Dragon Reborn twot-3

The Dragon Reborn twot-3 The Wheel of Time Companion

The Wheel of Time Companion The Fires of Heaven twot-5

The Fires of Heaven twot-5 Prologue to Towers of Midnight

Prologue to Towers of Midnight The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8

The Path of Daggers - The Wheel of Time Book 8 The Path of Daggers twot-8

The Path of Daggers twot-8 By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light

By Grace and Banners Fallen: Prologue to a Memory of Light Crossroads of Twilight twot-10

Crossroads of Twilight twot-10 The Gathering Storm twot-12

The Gathering Storm twot-12 Winter's Heart twot-9

Winter's Heart twot-9 Knife of Dreams twot-11

Knife of Dreams twot-11 New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)

New Spring: The Novel (wheel of time)